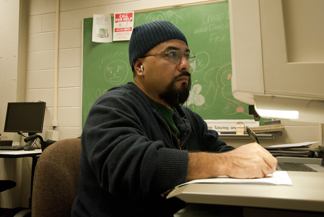

David Reid/The Collegian

By Mona Lisa Tucker/south news editor

Most people who attend colleges or universities can clearly enter and exit the schools with a level of ease.

South Campus student Enrique Martinez does not have that luxury.

As a child, he developed a juvenile form of macular degeneration, which deteriorated the nerves in the retina of his eyes.

“It begins early in life, and it stops,” he said. “It actually develops scar tissue. Even as far as second grade, I remember not being able to see the board.”

Martinez did not realize his sight was different from others until he was about 13 years old. The school officials started helping him, and then a series of visits with specialists began, he said.

“That was a struggle all the way up to high school because I didn’t want to let people know that I needed help,” he said. “I didn’t want girls to know that I couldn’t see. I didn’t want other people to know that I couldn’t do my homework.”

Therefore, he played the role of the tough guy pretending not to need or be interested in school.

“Somehow, I made it through high school, but I gave up on school until just recently in my adulthood,” he said. “I was able to realize, to overcome, by just facing it.”

Martinez must use several devices to help him complete assignments.

“I have to have either special software, recorders or large-print paper so that I can be able to see,” he said. “All of that is provided by the disabilities office. As far as getting to places, I have to make sure that I show up early or a day ahead. I get ahead of the game by memorizing everything.”

In terms of leisure things such as going to the cafeteria, he just asks questions.

His wife Olivia Martinez said other than some things she and their children help him with and the places she drives him, Enrique does a lot on his own.

“He has become so self-sufficient himself that he knows the bus routes pretty much by memory,” she said. “He knows how to get around and manages to get to where he needs to be if he has to.”

Martinez also handles paperwork.

“He has his own business and investments, and he takes care of those,” she said. “He has CCTV [closed-circuit television]. It’s attached to a television. It magnifies whatever he puts under in the viewing area, and it magnifies it on to a screen so that he can read.”

Olivia deals with some paperwork, but Enrique has learned how to use more technical devices, which furthers his independence.

“It’s not that much that I have to help him with, just small little things that come up,” she said.

For example, Olivia and their children make sure forks and knives are pointed downward and spoons upward, and whenever they are on family outings, they use their own safety systems.

“Which is a way of him knowing that he’s not going to get hurt, but then he knows that that’s the way we’re doing things,” she said.

Olivia is proud of Enrique and all his achievements.

Robin Rhyand, instructional assistant, said Martinez is the success story disability support services is most proud of. Enrique reminds Rhyand of “The Tortoise and the Hare,” where the slow turtle wins the race.

“He is a stellar student. He puts in the work. A lot of students just think that they can show up and somehow get a degree. You cannot. You have to do the work,” she said. “He does not let his disability of visual impairment hinder him in any way whatsoever. In fact, he finds ways to compensate.”