A state law prohibiting hospitals from removing life-sustaining technologies from a pregnant woman, regardless of the wishes of the victim and her family, needs to be repealed.

Former TCC student Marlise Muñoz, 33, was kept on a ventilator with an artificial heartbeat for more than seven weeks in hopes that her baby could survive to birth at John Peter Smith Hospital in Fort Worth. Her husband, Erick Muñoz, found her unconscious in their home in November, and she was pronounced clinically and legally brain dead after drugs and electric shocks were used to restart her heart.

She remained in this condition against her wishes for after-death-care along with the wishes of both her husband and her family, who had to sue the hospital arguing the law applies only to the living, not the clinically and legally brain dead. A judge agreed, and Marlise Muñoz was removed from life support Jan. 26.

The law at the heart of the debate, the Texas Advance Directives Act, is swayed in favor of abortion-rights opponents and leaves families that do not wish to wait and see if, in fact, a healthy baby is born in the end with a huge emotional and financial burden.

One could debate this issue from several angles including deep moral discussions involving when life actually becomes life and God’s will for life to thrive, but let’s take a look at a side of the debate that isn’t getting talked about much — the financial burden to the family.

According to a report from Princeton University, the average cost for the first night in intensive care for a patient requiring mechanical ventilation is $10,794, $4,796 for the second night and $3,968 for any following nights. Calculated out over a six-and-a-half month period, that is more than $785,000 in hospital expenses alone. Not to mention time spent away from work, court costs associated with fighting the issue and any immediate health care the baby may need if it survives to birth.

It is absurd not to give the victim’s wishes any consideration or the victim’s family a choice in the matter, simply based on the money aspect alone.

Muñoz’s attorneys argued that the unborn child was malformed because of her mother’s state. That could have meant a lifetime of medical expenses for the father. There isn’t a ton of data on this subject on either side of the argument. That is a choice he should be allowed to weigh.

Another issue with the law is that it does not allow for the family to grieve properly and forces them into the courtroom under intense public scrutiny, adding extra pressures to an already impossibly stressful, personal situation.

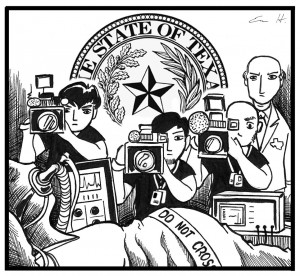

If there were no law, the situation would be a private matter where the husband and family sit with doctors and decide in a private manner how to proceed. Instead, this has become a national story, and a father and family were forced to put aside emotions and enter a courtroom to decide the fate of Muñoz and her unborn child.

This is not to say The Collegian believes life-support should be ceased in any situation like this. And if the family’s wishes were to see the situation through to birth, then by all means, they should try. It’s the Texas Advanced Directives Act not giving the family a say either way in the matter that is appalling.

Now, the Muñoz family deserves to grieve and move on with their lives. It’s a shame, though, that this law turned an already terrible situation upside down.