By Matt Fulkerson/sports editor

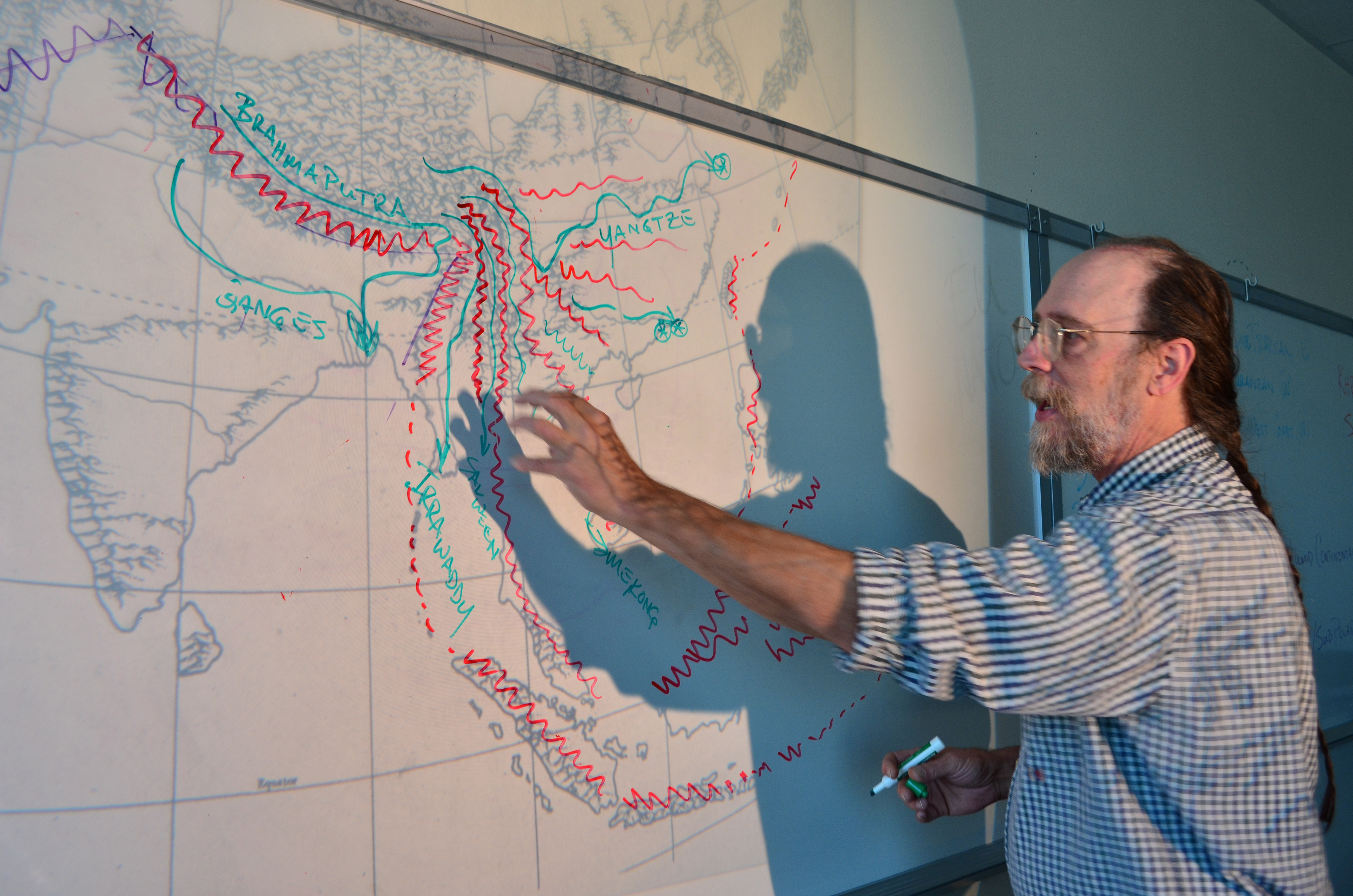

With an easygoing Southern drawl and a braided pony-tail falling down his back, William Miller – or Billy Bob, as he prefers to be called – is hard to ignore.

His relaxed manner at times disguises a lifetime’s worth of college experience. While he says he may not be one to talk about himself, he is more than willing to discuss his ideas with students.

Miller can talk about everything from his thoughts on evolution and plate tectonics to algebra and ways to fix the public education system. Despite the wide array of topics, his ideas were by no means disjointed. Each thought naturally led into the next.

“He’s definitely one of the most interesting teachers I’ve had here,” said NE student Michael Logan, one of Miller’s former students. “He’s not really ‘by the book.’”

The ability to venture away from the textbook is what Miller says draws him toward collegiate instruction.

“One of the reasons I teach college-level courses is that nobody tells me what to teach,” he said. “The school provides a general course syllabus, but to me that’s the floor, not the ceiling.”

Miller says he believes a major failing of public schools lies in the issue of bureaucrats deciding what and how teachers should teach.

“Biologists decide what biology is, not school boards,” he said. “The teacher’s job is to provide the most current science available.”

Along with this idea, Miller says that school boards, administrators and other teachers should not decide how a teacher leads a class.

“Matisse didn’t tell Picasso how to paint, and Picasso didn’t tell Matisse how to paint,” he said. “But they admired each other’s work.”

Currently, Miller teaches geography and geology courses on NW Campus, but his assignments take him across the district.

“I’m more or less a lone wolf,” he said. “My office is the tan Chevy in the parking lot.”

His background in science gives him a unique perspective on the interrelatedness of its various disciplines and a belief that attempting to categorize them is difficult, if not impossible.

“He’s kind of hard to follow sometimes,” said NE student Brian Thompson. “He switches ideas around a lot, but it’s great information.”

For Miller, while these ideas may seem unrelated, it’s the gray areas that bring them together.

“When do you stop calling it physics and start calling it chemistry? When do you stop calling it chemistry and start calling it organic chemistry? When do you stop calling it organic chemistry and start calling it biochemistry? When do you stop calling it biochemistry and start calling it biology?” Miller asked.

“The stuff is what it is. As soon as we put a definition on it, we have to start listing the exceptions.”

Instructing toward the lowest common denominator, especially in the realm of science is detrimental, not just to the student but to the teacher as well, he said.

“They think they’ve got to reduce it to a form the audience can take, but as soon as you do that, you’re either incompetent or a liar,” he said.

Rather than work at the lowest level of understanding or teach toward the average middle ground, Miller says he would rather challenge them to think beyond their beliefs.

“My first major professor said, ‘If all you do is take the average of things, you have destroyed everything interesting that went into it,’” he said.

Miller likens the job of teacher to that of an improvisational jazz musician taking the stage for an impromptu performance.

“When I walk into class, I’ve got an idea, say ‘igneous rocks.’ That’s all I know,” he said. “The rest is just riffing on that idea.”

For students, the end goal of school should not be learning what is already known but to rise above the levels of previous generations, Miller said.

“The whole idea is that you’re supposed to be smarter than your parents,” he said. “That’s the goal, and all we can ask of anybody.”