By Colt Langley/managing editor

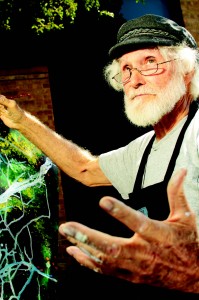

From living through the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression of the 1930s, Korean War veteran Paul Maginnis found a new love for art on NE Campus.

When Maginnis spoke about his time during the Dust Bowl, he said he felt “an immediate intimacy when experiencing the colossal monster that was as wide and high as you can see.”

During this time, everything in his home that he and his family lived in had been covered in dust. Something not in the home, he said, was an abundance of art. His interest in art would come much later in life.

In fact, he now has a series of paintings that are currently exhibited on NE Campus.

Maginnis, who will soon turn 78, spent the first 12 years of his life living in the plains of Oklahoma in a town called Okarche, 35 miles northwest of Oklahoma City.

When describing Okarche, he referred to the NPR radio show A Prairie Home Companion.

He said the town was “50 percent Lutheran, 50 percent Catholic and 5 percent Baptist. I know that adds up to be more than 100 percent, but that’s the point. It was A Prairie Home Companion-type town.”

Maginnis’ father later moved him and his family to Goshen, N.Y., for nine months where he said people thought, “Anybody who wasn’t of true religion [meaning Catholicism], they would go to hell.”

But his father didn’t like it up north, so he moved the family back south to Arkansas.

Later on, Maginnis joined the Air Force, staying from 1951 to 1955. At one point during his time, he was stationed at Manston air base in England, where he was in charge of purchasing and contracting supplies needed for the base. The U.S. used Manston as a Strategic Air Command base during the Cold War.

The base was small, he said. It held only 70-75 fighter planes.

At his barracks, “50 percent of the men were black, and 50 percent of the men were white,” he said. “I was in the middle. I thought both sides were equally noisy.”

This was during the time of segregation in the South when neither race could use the same restroom or water fountain. Having come from a Jim Crow state and witnessing these kinds of situations as a child, Maginnis was disgusted.

“When I was a kid, I thought it was pathetic and revolting to make so much out of being a little different of a human being,” he said.

After the military, Maginnis attended the University of Arizona to study history.

He describes his whole life as being a gadfly.

In 1968, he moved to North Texas and became a catastrophe insurance adjuster, where he determined the loss on residential and commercial buildings. With his job, Maginnis traveled around the country.

In his personal life, Maginnis has three children, all of whom live in the Metroplex, and a wife with whom he lives in Hurst.

It wasn’t until two years ago when Maginnis began his new hobbies on NE Campus — art and photography. He said he wanted to add art to his life to see if he had the ability to paint as well as understand line, form and color.

Art instructor Cynthia Hurt said she has seen changes in his work since his time at TCC.

“His work is fueled by his philosophy about life and death allowing the experimental process of paint to become a natural process much like itself,” Hurt said. “He has developed a style unique to itself and works on a large scale, drips and splatters and turning and spinning the canvas to direct the drips, allowing gravity to take over. I would have to say they’re [his paintings] very Darwinian.”

Maginnis has come up with names for some of his techniques. When he merely just drips drops of paint onto the canvas and turns them to let gravity take over, he calls it “drip and run.”

When painting with acrylics, he likes to use a syringe, a technique he calls “syringe, shoot and run.”

Maginnis credits Hurt for inspiring these techniques, saying that she once told him last spring to be more “organic,” meaning letting the piece take on a life of its own.

When explaining his own philosophy of his art, Maginnis says transformation is key.

“Darwin’s theory of evolution is bedrock for me,” he said. “Bedrock because I’m in this context that’s consistent with the law of energy — in that, energy and light was never created and will never be destroyed, just transformed. In art, it’s transformed through color, light and sight.”

For inspiration, Maginnis likes to visit Texas places like Enchanted Rock and Caddo Lake. He also said his teachers and classmates have inspired as much if not more than any other well-known artist.

While taking photography classes on campus, Maginnis has become friends with photo lab manager Mark Penland. Penland said he admires Maginnis’ art and treasures him as a friend.

“I think his work is deeply felt,” Penland said. “He’s an old hippie — an old radical. He’s really inspiring. He gives me a model for something I could be when I get older.”

His work is currently being displayed in NE’s J. Ardis Bell Library and will be up until Oct. 15.