By Mark Bauer/se news editor

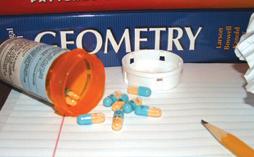

Much like athletes competing for a position on a professional sports team, students looking to enter colleges with tough admission standards can be susceptible to the allure of illicit drugs that promise to enhance concentration and overall academic performance.

A national study conducted by the University of Michigan and the Harvard School of Public Health in 2005 indicated that 7 percent of college students across 119 college campuses admitted to having used prescription medications for non-medical purposes—such as all-night study sessions—in the previous year. The number rose to 12 percent when compared with lifetime use.

University of North Texas student Erin Michelle Baima said she took Adderall, a popular prescription medication used to treat ADD and ADHD, during her freshman year to help stay awake and study for tests she otherwise would not have been able to study for.

“[Adderall] helped me because I was able to concentrate and study for long periods of time and get more homework done,” she said. “I do not have a very long attention span on my own, so I feel like it was a benefit to me at that time.”

The FDA, amid concerns from a science advisory panel in 2006, added a black box warning to the labels of prescription medications used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

The black box label, the most serious of the FDA’s drug-risk warnings, highlights risks associated with misuse of the medication, including drug dependence over prolonged periods of use.

Additionally, misuse of amphetamines, a main ingredient used in the stimulant drugs, may cause sudden death or serious cardiovascular complications.

But many students, like Baima, are not aware of the risks associated with the pills because they have never seen the label.

“ I got the pills from friends and they were always given to me in a plastic sandwich bag,” she said.

Still, Baima said even if she had known the risks, it probably would not have affected her decision to take the pills in the first place. Her roommates and friends were taking the medications to help them study as well.

However, Baima ultimately discontinued using Adderall after the first semester of her freshman year because she did not like the way it made her feel.

“ My heart beat was too fast when I took them, and it did not make me feel good,” she said.

For SE Campus student Shawn Thompson, the health risk does not outweigh the benefits.

“Although taking Adderall enhances a person’s concentration, to me the side effects are not worth it,” he said. “Besides, I don’t need a drug in order for me to concentrate or perform better on tests.”

But what if the pills are not actually helping students attain better grades?

Dr. Charles Overstreet, psychology professor on South Campus, said if the stimulant is used enough, students may build a tolerance.

“Your ability to concentrate will actually drop,” he said.

Overstreet said students most often use the pill in place of sleep, thinking it will leave them more time to cram for a test.

The sleep depravation impairs the students’ ability to encode and makes it difficult to retrieve that information when they need it most—such as while taking a test.

The student who puts off studying and takes the medication to boost his or her concentration is no better off than the student who studied in advance and gets an adequate amount of sleep, Overstreet said.

“Stimulants won’t replace sleep,” he said.

While Adderall provides support for people with ADD, Overstreet said, people with prescriptions from licensed medical doctors are the only ones who should use it.

Otherwise, possession of Adderall is illegal. And the consequences can be tough.

“It’s the same as buying pot or heroine,” he said.

Just two weeks ago, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported a Missouri high school student admitted to selling prescription medications to friends.

The 18-year-old student was charged with drug possession and distributing a controlled substance near schools, both felonies.