Robie Robinson, director of safety and emergency management at TCC, works around the clock to keep the campuses and people on them as safe as possible.

“It’s not as fun and sexy as being a superhero,” Robinson said, chuckling. “When things are bad, I get to make them better.”

Robinson and Kirk Driver, coordinator of emergency management, work side by side to implement strategies in case of a disaster.

“You hope you never have to know this stuff,” Robinson said. “But in the event of a disaster, people need to know what to do, and we put these things in place to lower the tension.”

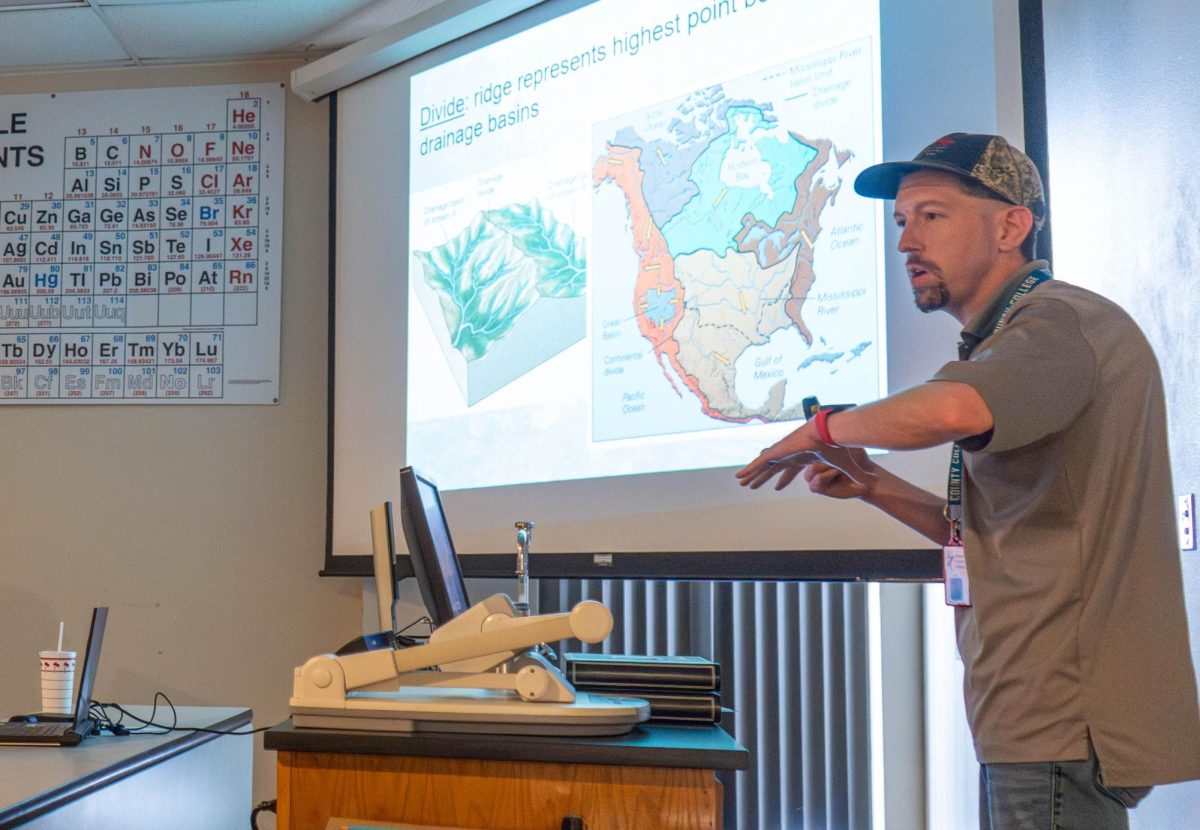

Robinson has taught emergency management at both TCC and the University of North Texas. His first semester in the classroom happened to be the fall of 2001.

“When 9/11 happened, Kirk and I were already professional paranoids,” Robinson said. “It created a window for us to reach out to the people. Our world in emergency management didn’t change right away, but the people’s perception of us did. They said, ‘We’re interested in what you have to offer now.’”

Since 2006, Robinson has been a commissioner of the Emergency Management Accreditation Program, a nonprofit organization that sets standards for emergency management quality. He currently leads an EMAP team working in Uganda to help devise a new plan of action when disasters occur and to assist with security.

“They have humanitarian disasters on a scale that we are not used to.” Robinson said. “This is 300,000 people, literally leaving everything they have behind and running across the border from another country.”

At TCC, Driver and Robinson work on ways to get information to students, faculty and staff about emergency procedures. Among current projects are installing video cameras around campuses, augmenting and improving CampusCruiser for better workability with cell phones and using digital signboards and message boards to make information quickly available for students.

“The only thing you really need to do in the event of a disaster is leave,” Robinson said, “but a simple act becomes very complicated when you’re dealing with a large group of people. Suddenly, they have to leave — at an unplanned time, using an unplanned route, for an unknown reason, sometimes at an accelerated speed, all at the same time.”

A sense of humor helps in this line of work, Robinson said.

“Think of one positive thing that Kirk and I need to focus on each day,” he said. “You’re going to have trouble finding one.”

Driver and Robinson engage in a playful banter in the office, so it’s hard to believe the job requires extensive planning and thought over disastrous situations.

“And if you come into a meeting being a Debbie Downer … they’re not going to invite you back,” Robinson said.

Emergency management can be a fuzzy field to work in, Robinson said. He finds it interesting because it’s hard to say if and when things are going to happen.

“When it reaches a point where you don’t have the resources to cope, that is a disaster,” he said.

Working in emergency management means finding ways to cope with natural disasters and prevent conflicts and even having to go in should something go wrong, he said.

Robinson originally wanted to enter emergency management while volunteering to fight fires.

“The inspiration came from people who are fighting fires and assisting through ice storms and aren’t actually getting paid to be there,” he said.