By Joshua Knopp/managing editor

Faculty and staff tell students relentlessly to attend classes, and next spring, the consequences for not doing so could be more severe than a lower grade.

Next semester, a mandatory attendance policy will go into effect which will allow teachers to drop students who miss 15 percent of their classes. For a 16-week semester, that’s five sessions for classes that meet twice a week and eight sessions for classes that meet three times a week. The decision to drop will be at the discretion of the teacher and should come after multiple warnings sent through WebAdvisor, said Anne Drake, who helped make the policy.

Drake, NE learning center coordinator, is also chair of the joint consultation council, a committee of faculty association officers from each campus that communicates with the board of trustees. She said the policy is a tool to encourage students to get to class more, which will probably improve their grades.

“It’s all about student success. Students don’t succeed unless they attend class,” Drake said. “Most studies show that students will come to class more if there’s an attendance policy in place, and if students attend more, they’ll succeed.”

Drake said the policy is relatively lenient, citing that nine of the 10 largest community colleges in Texas have mandatory attendance policies that are stricter. Drops by this policy are subject to TCC’s appeal system because the policy isn’t meant to drop students with an active desire to be in the class, she said.

“If a student is in a car accident and calls the instructor and keeps up with their classes, they’re not going to get dropped,” she said. “This is not a punitive policy. This is for students who make no attempt.”

The policy is almost directly transplanted from the mandatory attendance policy that was placed on developmental classes last summer. Drake says the policy marked an uptick in student retention and teacher happiness. Cathleen Stevenson, who has taught developmental courses for four years, said she can attest to this.

“It fosters a deeper relationship with the instructor and student because

you have so much more interaction with them,” she said, explaining that an instructor will have an easier time helping a student who has been there every day than one who missed a month and is apprehensive about seeking assistance.

“Academically, they’re there in the classroom. They’re receiving the material. They know my expectations,” Stevenson said. “Their scores have definitely improved.”

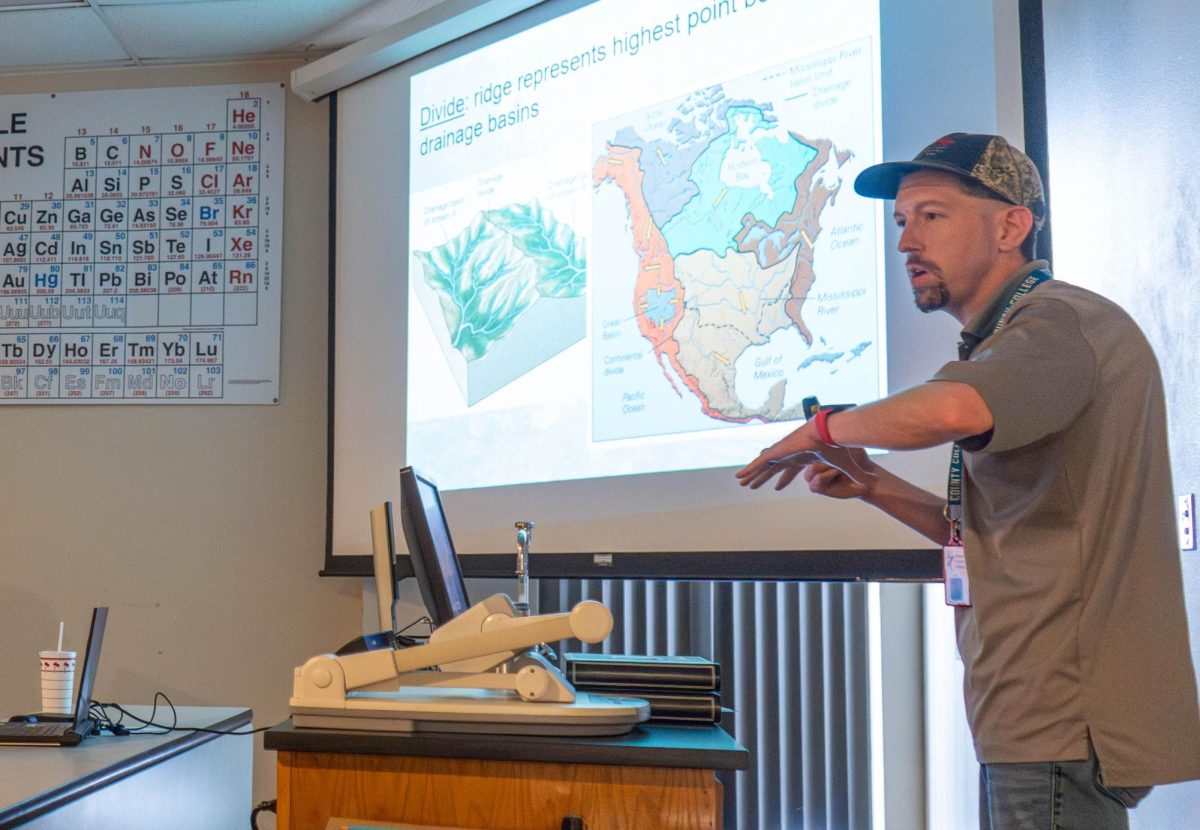

TR history adjunct Blake Williams said the policy will be a minor adjustment for him as a teacher.

“I really don’t think it will change it [his teaching style]. I still teach regardless of whether or not anyone’s here,” he said.

Williams said while he thought every teacher would approach it differently, he wouldn’t exercise the option lightly.

“I wouldn’t drop them because they miss a certain number of classes,” he said. “I’d try to find out why.”

NW student Kenneth Crisco said the policy might benefit students who can’t find a reason to attend.

“It’s probably a good thing. If that were in place, I wouldn’t have missed as much as I’ve missed,” he chuckled. “Good to have some form of motivation. That’s how I see it.”

Drake said the policy represents an effort to give the students more responsibility for their education.

“Most of our students come straight out of high school with these really rigid rules. A lot of the time, students go overboard with the freedom. They think because no one’s nagging them to do something, it must not be important,” she said. “What’s actually happening is people are treating them like adults instead of as children.”

NW student Andrietta Baxter, who graduated high school earlier this year, doesn’t think the policy is a problem but disagrees with the message it sends.

“I don’t think it [the policy] is a bad thing, necessarily,” Baxter said. “Coming out of high school where it was ‘you go to school or you go to jail,’ it’s kind of disappointing. It doesn’t seem like they’re treating us like adults.”