By Kenney Kost/editor-in-chief

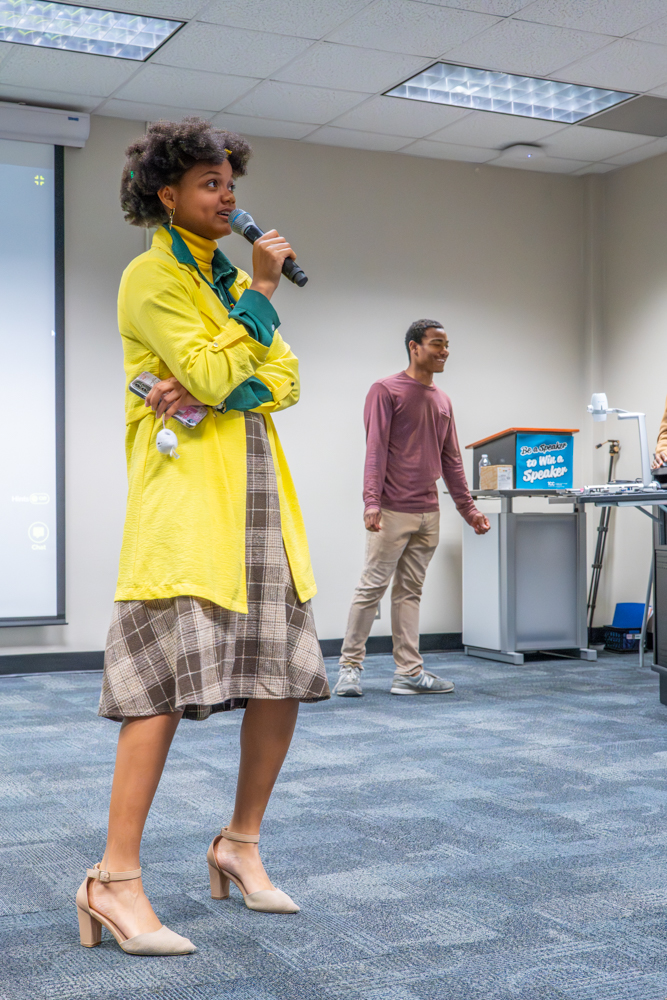

Sitting across the table, the 21-year-old girl looks like any other TCC student, smiling, laughing and sporting a backpack and laptop.

Her story, however, is far from ordinary, and her journey to Texas and TCC was long and trying.

She has asked to be called Samya for fear that her family will try to track her down and persuade her to come back to the family or possibly worse — kill her for dishonoring the family by rejecting an arranged marriage.

Her family is from the Middle East and steeped in a strict Muslim background. They moved to the United States when Samya was just an infant, she said.

“My mother has been mentally ill most of her life, and my father was very violent and angry,” she said. “I grew up with a dad I was afraid to talk to. Anything would set him off. He would come into my room, throw me against the wall and beat me. And I wouldn’t know why.”

The physical abuse stopped when she was around 16, and it wasn’t visited upon any of her younger siblings, just Samya and her two older brothers.

“I’m not sure why it stopped,” she said. “Maybe he got older and calmed down.”

The older Samya got, the more her father tightened his grip on her life. She was enrolled in public schools until high school when she was told she would be home-schooled until graduation and couldn’t have non-Muslim friends.

She was also forbidden to participate in any extracurricular activities, and her only communication with anything resembling a friend was with students who attended Islamic school on the weekends.

“They kept me locked inside the house most days, and I wasn’t really even home-schooled,” she said. “I was being taught how to take care of a family, cooking, cleaning, doing the dishes and laundry. I was learning how to be a submissive housewife.”

In May 2010, Samya was getting ready to graduate high school and planning her next move.

“I was nervous and excited trying to figure out what’s next, what college I was going to attend,” she said, “things most 18-year-olds are supposed to be doing and be excited about.”

Then, one day her whole world changed — she connected to the Web.

Her father gave her an iPod Touch to listen to music, unaware of its Wi-Fi capabilities.

“I connected to the world through Twitter,” she said. “I talked to Muslims with varying degrees of faith, extremely religious to extremely liberal, about the values my family held and Islam.”

The responses she received on Twitter from the Muslim community varied. Many of them felt just as her family did, that it was her duty to honor her family and accept the Islamic values they were instilling in her, she said. Others offered comforting words and wished her well. But nothing, she said, got her any closer to a solution.

At this point, she already had begun having doubts about her religion, which she suppressed.

“I understood and believed the theory of evolution,” she said. “I began to realize the Adam and Eve story is contradicted by this and began searching for answers. I begged God for answers. I was extremely depressed.”

While still speaking with Muslims, Samya also began talking to several people from the atheist community. One in particular, a man named Craig, got under her skin.

“Craig was an asshole at first,” she said. “But he talked about the scientific method and told me the first thing I needed to do was to quit trying to find things to prove my religion was right and start looking for things to disprove it.”

With all of these thoughts going on inside her head, Samya got in the family vehicle and headed to her graduation ceremony in June 2010. While waiting for her name to be called, watching the others who graduated with honors and scholarships, she began to fall into a depression again.

“When it got to me, they called my name and nobody clapped, not even my family,” she said. “I didn’t get any awards or scholarships because I wasn’t allowed to put in the extra time for any of that. I felt horrible because I knew I could be one of those graduating with honors, but I was held back.”

While others celebrated with their families, Samya was expecting hers to celebrate her being the first in the family to graduate high school. But her father was in a hurry and upset. On the way home, they ate fast food in the car for a graduation dinner, and her father asked her why she didn’t graduate with awards and scholarships.

“I couldn’t believe he was asking me, and I lost it,” she said. “I screamed that it was his fault because he never let me put in the extra work.”

Later that evening, Samya would attempt to take her own life.

“My dad had a ton of prescription drugs, so I proceeded to take an entire bottle of Tramadol, which is a muscle-relaxer,” she said. “I don’t know why, but I reached out to Craig, and he convinced me to go to the hospital.”

The doctor at the hospital recommended counseling. Her father disagreed, saying she needed only prayer and the Koran.

Around this time, two events changed the course of Samya’s life.

One evening before dark, alone in her bathroom, she felt thirsty and hungry from fasting for Ramadan, the Muslim month of fasting from dawn until sunset, and took a long look in the mirror.

“I remember sitting there, looking into that mirror, and it suddenly hit me — there is no God,” she said. “I looked down and took a drink of water and felt free for the first time in my life.”

She kept her thoughts to herself and her Twitter friends and went about her days thinking and searching for answers.

“It came down to not enough evidence, and I was pushed toward the pro-science views I already held,” she said.

Then came a visit from her uncle who lived in her homeland in the Middle East.

“It was just him and me outside, and he proceeds to tell me about an arranged marriage my father was secretly planning for me with someone from my homeland,” she said. “He said the only reason he was telling me was because he thought it was wrong for my father to be keeping it from me, not that the arrangement was wrong.”

Samya expressed her opposition, and her uncle threatened to kill her if she refused it, she said. She knew at this point she had to find a way to leave.

“My family had agreed to let me start classes at the community college near us around this time,” she said. “Instead of actually enrolling, I just saved the money they gave me for classes and books and started trying to figure out how to get out. Craig suggested I speak to a counselor.”

Samya spoke with a counselor at the community college that directed her to a social worker. The date was set. Samya was still being taken to school by her father to keep up the act, and each day she would take a little bit of her stuff and keep it in a locker. On the final day, 18-year-old Samya packed the rest of what she needed, hugged each family member and got in the car to go to school for the last time with her father.

“I left my phone and a letter for them saying ‘I have to live on my own, I want to become my own person,’” she said.

A social worker was there to take her to a shelter, and Samya took the final step in leaving behind Islam and her family.

“That was the first day I took off my scarf. I felt naked,” she said. “I still wear a lot of layers and clothing around my neck. It comforts me.”

That night, a worker from the shelter took her to the bus station and bought her a one-way ticket to Texas where a couple from Metroplex Atheists had offered her a free place to stay in their home.

“I was anxious and scared to get on that bus,” she said. “I kept telling myself, ‘I need to do this. I need to be happy.’”

Samya said she felt overwhelmed when she truly started thinking about crossing several states and being on her own once she arrived in Texas.

“To put it perfectly, I was a deer in the headlights,” she said. “I had never had a job, a car, a license or any financial responsibilities. No one in my life prepared me for this because my future was supposed to consist of marrying a Middle Eastern man, cooking, cleaning, making babies and serving my husband.”

Metroplex Atheists was instrumental in her getting here and getting on her feet in the following months. President Terry McDonald remembers the first time he heard Samya’s story.

“My first knowledge of Samya was that a couple that are members of our group announced they had volunteered to help a young woman who was trying to break free from her family,” McDonald said.

Money was collected from the entire group, and other members contributed directly to Samya by taking her shopping and helping her get settled into her new life.

Randy Word, a member of Metroplex Atheists, was involved in coordinating the donations and sending out emails to coordinate her getting here, getting a legal name change and new identification. Word put up the $1,500 for the name change.

“Changing her identity took a lot of work from Metroplex [Atheists] as a whole,” Word said.

Word said the reason his organization chose to help goes back to a humanist point of view.

“We kind of take the Golden Rule to the next level and simply say, ‘Do no harm and help others,’” he said. “It comes down to empathy and compassion for fellow humans. I’m sure a Christian church would have done the same thing based on their values.”

After arriving in August 2011 and staying at various places with people from Metroplex Atheists, Samya more than a year later was enrolled in classes at TCC and, for the first time in her life, was paying her own rent at her own apartment.

“I have a roommate who is a great friend. I’m working on my fifth semester at TCC, and I have a full-time job,” Samya said. “I love my life. I wouldn’t go back to that ever again. I do miss my family and worry about my 16-year-old sister who is going through the exact same thing I did when I was 18, but I have freedom and, for the first time in my life, I am not depressed.”