By Linah Mohammad/reporter

While thousands of Americans were terrified by the recent Ebola outbreak in Dallas, fear was out of the question for one Liberia-raised SE Campus library specialist.

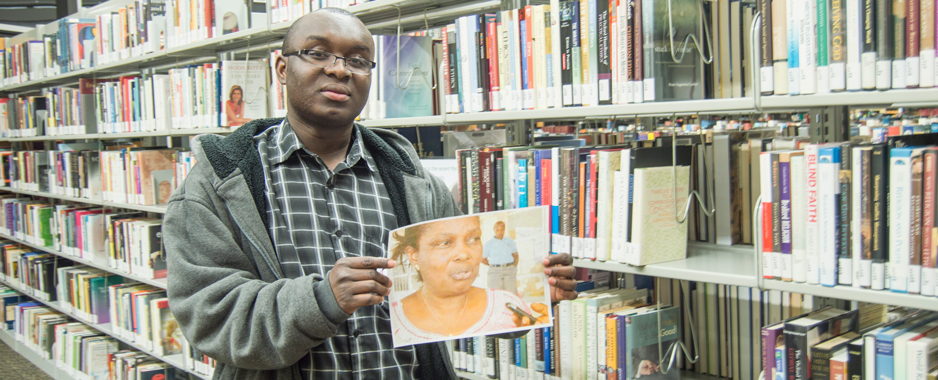

“My wife is Liberian, my sister is the chief medical officer in Liberia and all of my family is in Liberia,” said Edmund Tamakloe, 26.

Ebola is thought to have begun in the nearby West African nation of Guinea with two children who ate animal meat containing the virus. Their families then caught the disease from them, which in turn spread the disease to Liberia, where Tamakloe’s family lives.

“At the beginning, nobody believed the government when they first announced the Ebola outbreak,” Tamakloe said. “Instead, thousands started rioting against the government saying, ‘They’re lying to us.’”

The library specialist said the government’s actions led to distrust among residents.

“A lot of organ harvesting had been already going on,” he said. “People didn’t want to listen anymore. They were not going to believe anything their government had to say. So they started dying on the streets.”

Ebola needs hosts to survive and grow. As the virus moved into cities, it found its hotbed.

Liberian families are large, and sharing food from the same platter is common.

When they go to Friday prayer or Sunday services, they worship in large groups.

In addition, they bury their deceased, not cremate them. And their markets are on street corners.

“It’s not like we have a Wal-Mart,” he joked.

Ebola changed Liberian cultural values.

“Part of your culture dies, and that’s why people did not want to believe the outbreak,” he said. “People couldn’t worship, shop or even eat the way they used to.”

Eventually, hospitals ran out of space, and people were abandoned to die in the streets.

Bernice Dahn, Tamakloe’s sister and the chief medical officer in Liberia, had quarantined herself after her assistant died of Ebola.

Dahn said she isolated herself from the world for 21 days.

“She did it for the benefit of society and to set an example,” Tamakloe said. “Of course, I was afraid for her, and I was worried so much, but talking to her is different than talking to my cousin, for example, because when all people knew was fear, she made me feel that my fear was measured.”

Tamakloe’s personality helped him stay calm at times of unease.

One of his librarian colleagues, Sharon Holcomb, noticed his demeanor.

“There was no significant change,” she said, “although he was very concerned about his family. He didn’t mention it unless you asked him. He’s not one to burden his co-workers. He’s very professional.”

Ricardo Garcia, a co-worker with Tamakloe, said that he only voiced worry about his sister, Dahn.

“At least that’s the only person he expressed his concern about to me,” he said.

Even after the recent Ebola breakout in Dallas, Tamakloe has maintained his positive outlook.

“I was not irrationally afraid because not only did I know the dangers of Ebola,” he said, “but I also knew the risk levels and what it would take me to get affected. When you know too much about something, especially if it is dangerous, it creates a balanced fear. We are only afraid of the things that we don’t know.”

Dahn was recently released from her quarantine and is Ebola-free. And Tamakloe’s family is doing well. However, his heart is never at ease.

“I worry about them every day. I pray for them every day,” he said.