Photo by: Linah Mohammad/The Collegian

By Linah Mohammad/se news editor

The car bombings, all the dead bodies in the street. The sounds of bullets and the last moans of the wounded.

This is what every day in Iraq looks and sounds like.

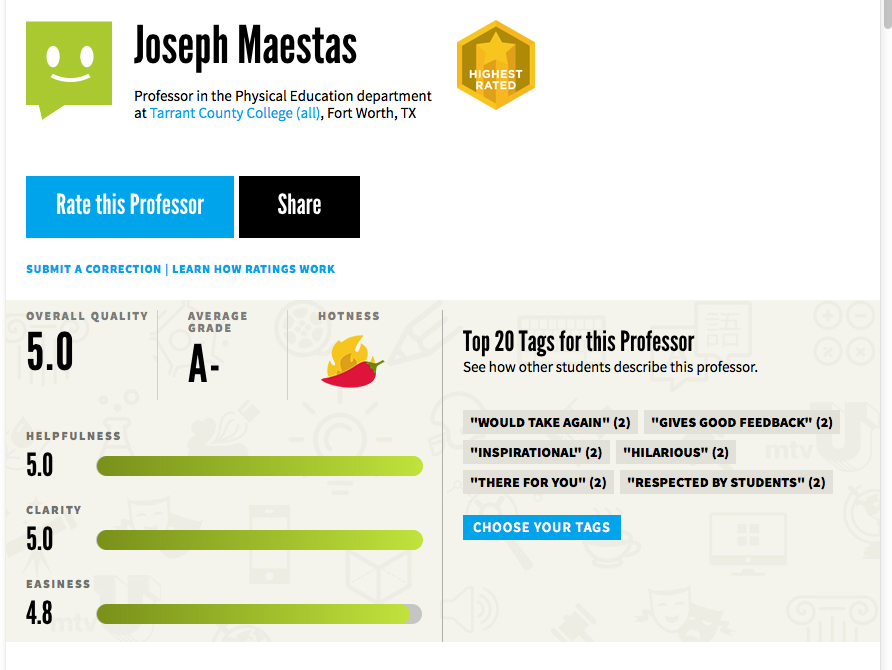

Huda Alsaheb of Nasiriya in southern Iraq and Ahmad Alnaimy of Baghdad, are two TCC students of many who suffered in their Mesopotamian homeland.

“My dad left Iraq in 1997,” said Alsaheb, a SE Campus dietetics student. “He came as a political asylee because he was opposed to Saddam Hussein.”

Alsaheb and her family moved to Jordan in 1999 and stayed there for two years. The Iraqi government, according to Alsaheb, knew that her dad had moved to the U.S.

“We had to tell them reasons why we’re leaving,” she said. “We promised them that we’re going to stay in Jordan, not go to the U.S. and that we are not in contact with my dad. We had to lie to them.”

After the Iraqi War and the fall of Saddam, Iraq fell into anarchy. Militias formed in several towns, each targeting a different group of people. The most commonly targeted groups were Sunnis and Shiites, the two major divisions of Islam.

Sunna and Shia were new concepts in Iraq. According to Alsaheb, these issues did not emerge until the invasion of Iraq in 2003.

“I have never even asked my friends if they were Sunni or Shiite,” she said.

Alnaimy, a NW flight program student, on the contrary, left Iraq in 2007 during the height of the Sunni-Shiite conflicts.

Photo by: Linah Mohammad/The Collegian

“You couldn’t be safe at all,” Alnaimy said. “You could die any minute. If you’re not with a certain group of people, then you’re against them.”

Shiites killed Sunnis. Sunnis killed Shiites. They even killed because of people’s names. Shiites would kill men called Omar, Abu Bakr or Othman while Sunnis would kill men called Hasan, Hussein or Ali.

“In 2005, a Shiite government was created,” he said. “They said it was their turn to govern now because Saddam’s regime had been Sunni. That’s how they looked at it.”

Alnaimy said he was raised Sunni, but they never discriminated.

“We never knew if our neighbors were Sunni or Shiite, even during Saddam’s reign,” he said.

After 2003, Alnaimy recalled, discrimination against religious orientations started.

Alnaimy’s dad, who is a teacher, was kidnapped in 2007. During that time, his family fled to Istanbul, Turkey, where they lived for a year. Then they came to the U.S. on a refugee visa.

“After everything he went through,” said Amin Eissa, a friend of Alnaimy, “Ahmad’s experience as an Iraqi living there made him appreciate life more.”

Since the assembly of the Shiite government after the fall of Saddam, issues escalated.

“Everything was controlled by Shiites,” Alnaimy said. “Sunnis had no rights. Shiites get to talk shit to us, and they take advantage of us. If you have a brother named Omar, you couldn’t call him by his name. If you do, they’ll kill him.

“They kidnapped my dad. Just because he was Sunni. Nobody knew where he was. We couldn’t ask questions.”

One of Alnaimy’s uncles was kidnapped before his dad was. He was found dead the next day.

“I still remember it. I went with them to pick him up,” he said. “His face was broken into pieces. We couldn’t even tell it was him.”

Alnaimy’s dad came to the U.S. in 2009. But he went back to Iraq soon after.

“My dad was a teacher for 25 years. He came here, and the only job he could find was at Wal-Mart,” he said. “My dad said, ‘I’d rather die in my land than just live here.’ He didn’t let us go back with him.”

It is still dangerous for his dad. Alnaimy said his dad tells them that they could get a phone call anytime saying that their dad was killed.

Iraq went to both extremes in a matter of years — from a strong central government to a chaotic land where the government has no control.

“It is true that Saddam was so strict on us,” Alsaheb said. “But at least, the country had some order. Iraqis were afraid of him. Now looting and murdering is common. There is no control. You can do whatever you want now and just get away with it!”

Alnaimy agreed with Alsaheb. According to him, Saddam’s regime was a dictatorship but, regardless, Iraq was better during his days.

The sanctions that were imposed by the different militias were a major factor in the creation of ISIS and its growth in Iraq.

“First of all, ISIS are neither Sunni nor Shiite,” Alsaheb said. “They are not even Muslims. They kill everybody, rape girls, take money and do whatever they want. As Iraqis, we think somebody is supporting them because where are they getting their artilleries and funds?”

Alsaheb has some family in land that is under ISIS control now. Her cousin is one of them.

“When I talked to him, he said he hadn’t left his home for two days because he’s scared,” she reported. “He even said, ‘ISIS might just invade my house, rape my wife and kill us.’”

Nonetheless, Alsaheb has other family members who are currently fighting ISIS in its bases.

“I have three cousins who volunteered to fight ISIS now,” Alsaheb said. “They have families, they have wives and they have kids. It’s really sad, and it’s very hard for us.”

Alnaimy has Sunni relatives in Mosul, a city that was under ISIS control. He said, ISIS seized their businesses, their houses and everything they owned.

“They told my cousin they weren’t going to kill him,” he said. “However, they said they’re going to claim his property, and he is no longer welcome to stay in Mosul.”

The Iraqi government is too weak and is nearly inactive, he said.

“There is a lot of corruption in the Iraqi government now,” Alnaimy said, “and people are not doing anything about it because they are scared of ISIS. It’s all a political game. It is funny how no one can stop them.”

Alsaheb agreed.

“The Iraqi government is not doing anything,” Alsaheb said. “There are no schools, no hospitals, nothing. It’s been more than 11 years since the war. Do something!”

“Iraq? … It’s over,” Alsaheb sighed.

Iraq is a lawless land now. It is a wreck, remnants of a land.

“I miss my country. I miss my town. I miss my family,” Alnaimy said as he looked down. “But there’s nothing I can do about it. It’s too dangerous.”