By Martin Paredes/south news editor

South Campus, at what was then Tarrant County Junior College, opened its doors in the fall of 1967 after a hectic two-year process of finding a chancellor, hiring a staff, finding a location, planning on top of more planning and finally completing construction.

In the weeks leading up to the first day of classes, constant rain halted construction and resulted in a parking crisis.

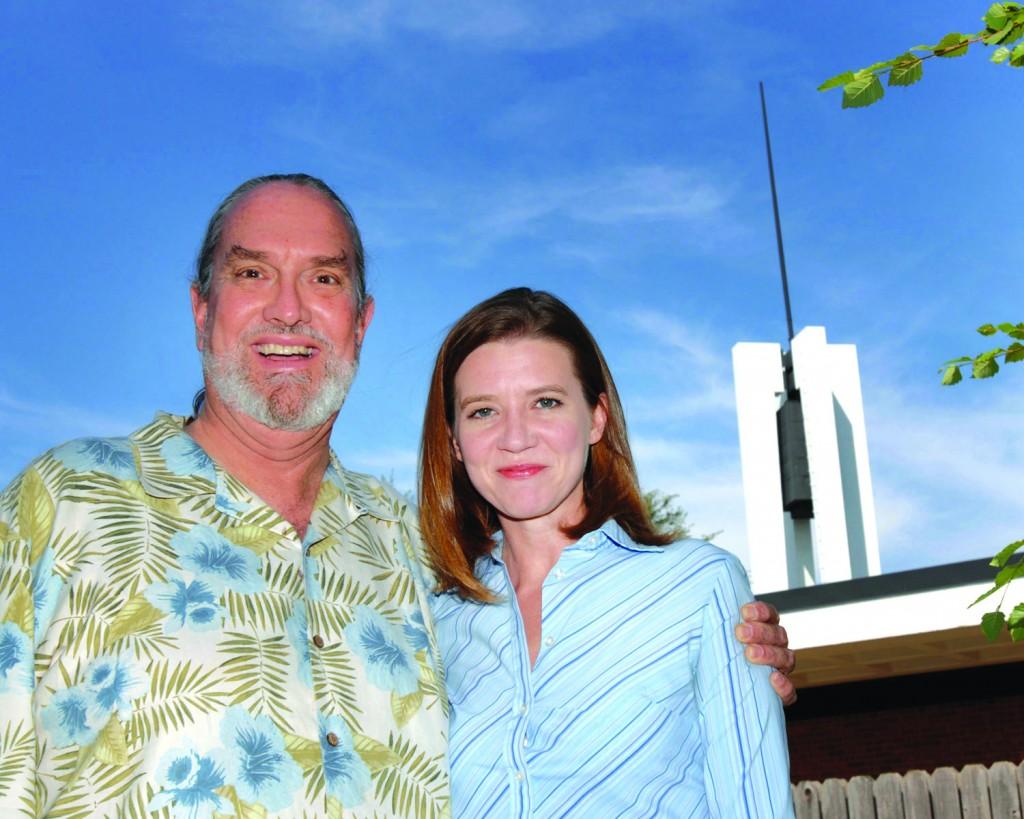

NE vice president for academic affairs Gary Smith was a biology instructor on South during its inaugural semester and remembers the chaotic scene.

“We had these torrential rains during the first day, and the kids were walking through heavy mud trying to get to class,” he said. “I don’t think we had all the sidewalks done yet either.”

South Women in New Roles coordinator Treisha Light arrived a year later as a 22-year-old psychology instructor.

Light was part of a group program called basic studies, which taught 100 students different core subjects like biology, psychology, sociology, humanities and English.

“It was an exciting time to be teaching in such an innovative program,” she said. “It was very unique because we were allowed to do a lot of experimental things.”

Smith said the creative freedom given to instructors started with the college’s first chancellor, Joe B. Rushing.

“Dr. Rushing set that tone for us,” he said. “He would say things like ‘I want you to be creative. I want you to be innovative.’ And that was for every faculty member. He wanted to make TCC a nationally known college for its innovation.”

Light said the times when she first started were much different from today, and it was reflected by the student body.

“When I first started, I had a lot of students who were on drugs,” she said. “I’ll never forget when (a student) called me one Monday morning and said, ‘Ms. Light! I’m down here in jail, but I’m going to get out and I’ll be back in class.’”

Despite their drug use, the “hippies” were usually pretty sophisticated, Light and Smith both agreed.

Smith would often suggest a book to his students on a Friday and have a line of hippies outside of his office ready to discuss the book on Monday morning.

“My former department chair once told me, ‘I’ve got to set up an appointment with you just to come and to ask a question because when I come down to your office, there’s students everywhere,’” he said.

South opened during the Civil Rights Movement, and Smith said that was noticeable during those first few years.

“We had to learn about one another in terms of racial adjustment, and there were some rough times in that,” he said. “We went through a lot of focus groups and sensitivity training.”

The women’s movement was also very much in effect, which gave Smith a lot of joy.

“I liked teaching those women that had been changing diapers for years and were now coming back to school because they were like sponges,” he said. “They wanted to learn, and they were excited to be out of the home having intellectual and adult conversation after dealing with kids for so many years.”

Smith said he was sad that students today are much more apathetic to those he first taught on South.

“The biggest change is the lack of curiosity,” he said. “In the ’60s and ’70s and ’80s, students were extremely curious about education. Today, many students just don’t seem to have that intellectual fire.”

Light said South has grown a lot in the ways it can help students.

“Where I’ve seen them make a lot of strides is in helping the nontraditional student,” she said. “We’ll give you another chance here and encourage people not to give up on education just because it didn’t work out in high school or at another college. I also think there are a lot more resources for students now than there used to be.”