Logan Evans

campus editor

Students who joined TCC’s virtual Women In STEM event were greeted by the brass voice of Billie Holiday crooning on a scratchy 1941 recording while they waited for the session to start. The sound conjured up a bygone era, when innovative women like Holiday were often chalked up to anomaly in the public eye.

Minutes later, two speakers appeared on screen to discuss one of many trends moving away from that idea — the growing number of women seeking careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

“Where were we, where are we now, and where do we go?” asked speaker Kayleigh Bowers.

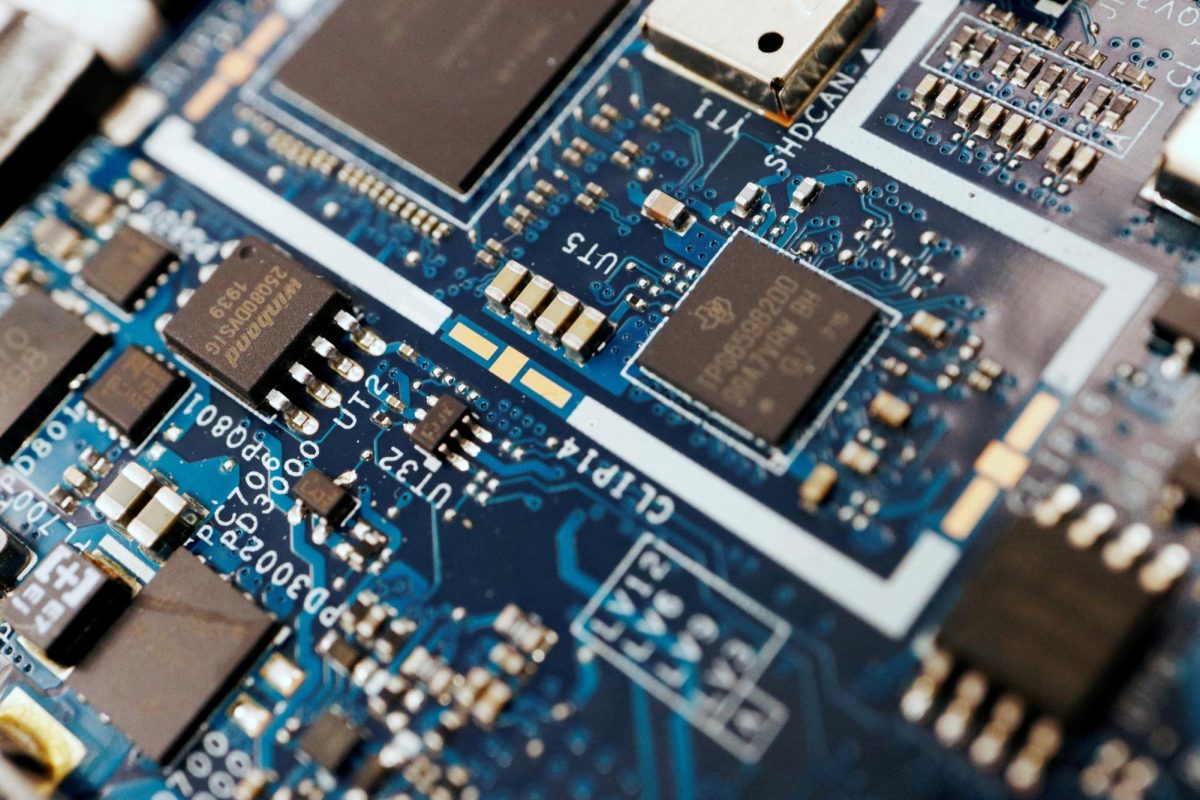

Bowers, an assistant architect at Lockheed-Martin, has spent the last seven years at a company on the cutting edge of aerospace. Having completed a business degree at the University of Texas at Arlington, she began in a supply chain but soon realized the technical side of engineering was calling out to her. She joined an electronic warfare team and spent several years working on the F-35 combat jet.

Now, Bowers works on developing advanced aviation cockpits. She and her colleagues examine the human factor of flying and use it to improve the technical side.

“Growing up, my mom was always into astronomy,” Bowers said. “We always had a telescope in the house. I really attribute my initial love of science to my mom.”

Bowers grew up as an athlete playing traditionally male-dominated sports. She was used to being the only girl on the team, something that prepared her for when she entered STEM.

“I came in and just worked as hard as I could and let my results speak for me,” she said.

Bowers pointed out that only a short time ago in history, social norms placed men at work and women at home with children. That’s changed, she said, and young women will start to see that STEM actually isn’t as male-dominated as it once was despite some lingering effects of the old norms.

Speaker Jennifer Kite, a learning lab manager for TCC’s automotive technology department, realized how big the gender gap can still be in some areas of STEM when she took her current job. The completion rate for an automotive technology degree at TCC is 92% male and 8% female.

Kite attributes this disparity to lasting effects of the “car craze” of the 1950’s, when men in the automotive world were lauded as greasy-handed mechanics and women were presented as pin-up models posing off to their side. In her leadership position, Kite works to steer away from these dated roles. She has a motto: “We’re not mechanics. We’re technicians.”

NW student government association president Rae Brown, who moderated the event, said imagery and representation are key to the development of young women and that any move away from restrictions of the past is a step toward a stronger future.

Bowers and Kite both consider themselves lucky in that neither has experienced overt discrimination in the workplace because of their gender, but small traces of past stereotypes can rear their heads from time to time. Kite still receives strange looks when she tells people she works in automotive. She doesn’t let it get to her. “We use our brains to diagnose vehicles,” she said. “There’s going to be dirt, but it’s not just greasy faces and greasy hands.”

Bowers believes the biggest benefit of a diversifying field is the unique results different viewpoints can yield.

“If you have 10 copies of yourself sitting around a table, maybe you’ll come up with good ideas,” she said. “But you don’t make the progress you could have made if you brought diverse perspectives, ideas and experience to the table.”

Bowers and Kite said it’s up to everyone to support progress in the field and help close gender gaps. Doing so will increase opportunities for all and usher in new ideas to advance STEM as a whole.

“You might break down that next barrier,” Bowers said. “Another young woman will see that you’ve broken that barrier and they might break the

next one.”

on misinformation in the news and the government.

Harvard professor speaks to TCC students about political division

The common ground between political leaders on both sides of the aisle has completely eroded over the last 50 years, says Thomas Patterson of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government.