Carlos Rovelo’s journey from civil war to Bush’s artistic inspiration

logan evans

campus editor / photographer

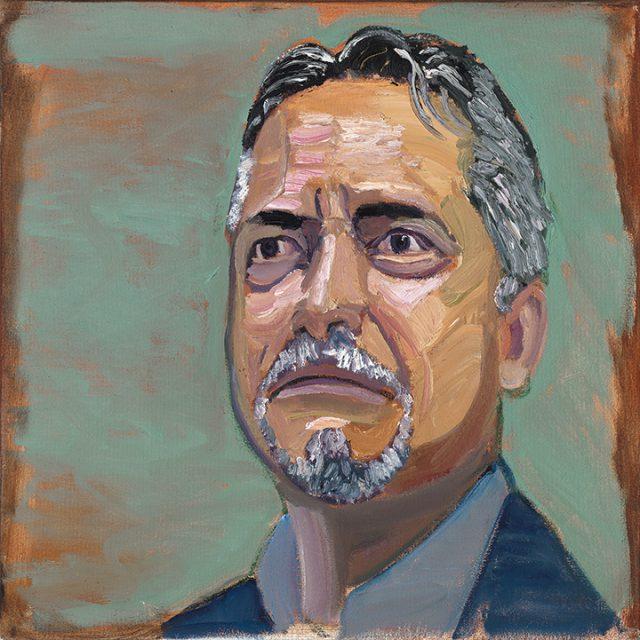

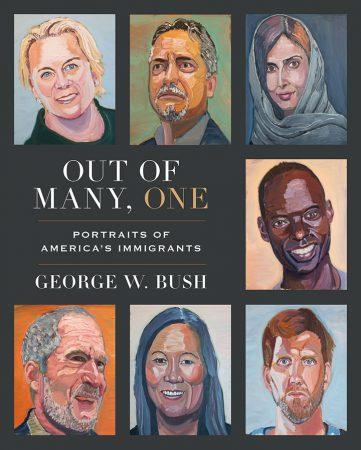

In a painting, South professor Carlos Rovelo sits up straight, his skin rendered in strokes of rust and amber. A fire burns in his eyes, brought to life by the artist — former president George W. Bush.

Rovelo, who escaped civil war in El Salvador 41 years ago, is one of the 43 American immigrants painted by Bush in his new book, “Out of Many, One.”

He is one of just seven featured on the front cover.

Rovelo said the question he’s been asked the most since the release of his book is how he made it from a war-torn country to TCC and the end of a president’s brush.

“It happened the way things happen in America,” he said. “It’s not a straight shot.”

Rovelo was born in Santiago de Maria, a city he calls “famous for coffee plantations” in a testimony in the book.

Rovelo was born in Santiago de Maria, a city he calls “famous for coffee plantations” in a testimony in the book.

The coffee industry drove El Salvador in the early 20th century, but the benefits weren’t reaped by many. Fourteen families controlled most of the wealth, creating widespread tension between the upper and lower classes.

The Salvadoran Civil War began when a coup placed a military-led junta government in power, resulting in the formation of an opposing leftist liberation front. From 1979 to 1992, over 75,000 people were killed, according to the UN.

The bloodshed often seeped into civilian life, with the recruitment of child soldiers and the terrorizing of Salvadoran citizens.

Rovelo was a teenager when his father, a business owner, was tortured by a military squad after refusing to choose a side in the conflict. He recalls racing through his city on a motorcycle with a friend, searching for his father and feeling the pull towards violence boiling over inside of him, too.

For a moment, it almost took him.

“I felt this sense inside of just becoming a mercenary,” he said. “We are born with certain values, and when those values are contradicted in plain view, it’s pretty dangerous.”

Rovelo’s family was forced to pay a ransom for the return of his father, who was mentally and physically incapacitated from the torture he endured. With the father figure he wanted to emulate struggling, Rovelo felt lost.

For years, he had dreamed of attending university in the U.S. After graduating high school, he applied for an I-20 student visa and was accepted to Wichita State University in Kansas.

When he arrived in the cold Midwest, he struggled to cope with an unfamiliar culture and the gnawing pang of what he’d left behind.

An American family took Rovelo in during this time. He remembers playing soccer with their children and marveling at their use of a microwave for cooking. They showed him a kindness and hospitality that he couldn’t understand.

He remembers having a conversation with the family about his gratitude.

“I really appreciate what you’re doing, but I can not repay you,” he said.

“Carlos, we are not asking for anything from you. But I know that down the road, you will meet another Carlos Rovelo. And that will be the moment for you to pay.”

Not long after Rovelo arrived in the U.S., Archbishop Oscar Romero was assassinated during Mass in El Salvador for speaking out against injustices in the country. Rovelo’s grandmother was in attendance and watched as the bishop was shot while breaking Holy Communion bread. All of this happened just a few blocks from Rovelo’s family home.

Not long after Rovelo arrived in the U.S., Archbishop Oscar Romero was assassinated during Mass in El Salvador for speaking out against injustices in the country. Rovelo’s grandmother was in attendance and watched as the bishop was shot while breaking Holy Communion bread. All of this happened just a few blocks from Rovelo’s family home.

When the news came to the U.S., Rovelo struggled to describe its gravity to his American peers with his limited English. He worried about his family and their proximity to political violence.

“There are moments when I wanted to go back,” he said. “Where is justice? Where is God in all of this?”

Rovelo, who was Catholic, began attending First Presbyterian Church in Wichita. The congregation understood the situation his family was in, and they petitioned a visa to bring them to the U.S.

Rovelo’s family arrived on Christmas day, 1980.

For the last 14 years, Rovelo has worked as a community college professor, teaching government and art history.

It was his passion for art that led him to meet former president Bush, who had taken up painting after leaving office in 2009. They were introduced in a gallery in 2019 by Jim Woodson, one of Bush’s art instructors.

Taken with Rovelo’s story, Bush asked to paint his portrait.

In conversations, the former president often asked Rovelo where he stood on current immigration issues, given his background.

“I told the president my position is always based on where we come from,” Rovelo said. “When we judge instead of wonder, we get into trouble.”

Rovelo believes that in order to move into the future, you must remember the past.

In 2004, he returned to El Salvador to attend his 25-year high school class reunion. He saw former classmates who had taken up arms in the war still struggling with injuries they received.

Many others, he learned, had died.

“I realized how drastically my life had changed,” he said.

Rovelo, now 61, hopes his inclusion in Bush’s book will help immigrant students understand the opportunity they have to build a legacy in the U.S. He thinks back to the American family who took him in when he first arrived in this country, and their request to pay it forward.

“This is a country, as an immigrant, you’re going to transform,” he said.

All 43 of Bush’s original oil paintings from the book are on display at the George W. Bush Presidential Center museum in Dallas through Jan. 3, 2022. The exhibit aims to “spotlight the inspiring journeys of America’s immigrants and the contributions they make to the life and prosperity of our nation,” according to their website.

All 43 of Bush’s original oil paintings from the book are on display at the George W. Bush Presidential Center museum in Dallas through Jan. 3, 2022. The exhibit aims to “spotlight the inspiring journeys of America’s immigrants and the contributions they make to the life and prosperity of our nation,” according to their website.

As he grows older, Rovelo looks to the past for lessons he can impart on his family and his students.

“I’m not as focused on me,” he said. “I’m fading.”

But his portrait is set forever in color, looking up — not away.