Logan Evans

managing editor

Set 30 years after the original film, “Candyman” is a sequel with purpose.

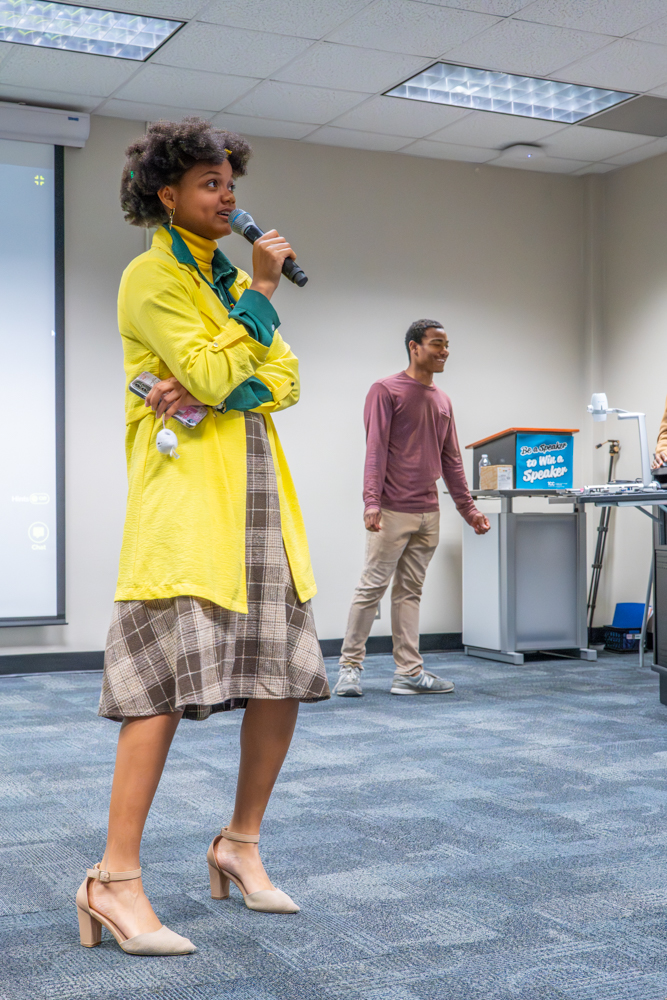

Yahya Abdul-Mateen II stars as Anthony, a visual artist struggling through the Chicago art scene. At a loss for inspiration with an upcoming piece, he visits the Cabrini-Green housing projects — the central location of the events in the first movie — and finds himself stalked by a timeless evil.

On a technical level, the filmmaking of “Candyman” is superb. The colors are deep, the sound design is gritty and visceral. Early on, the film uses an animated sequence to relay the events of the original film, and this sets the tone for a near-storybook quality that persists until the end credits. Visual beauty seeps into thematic terror.

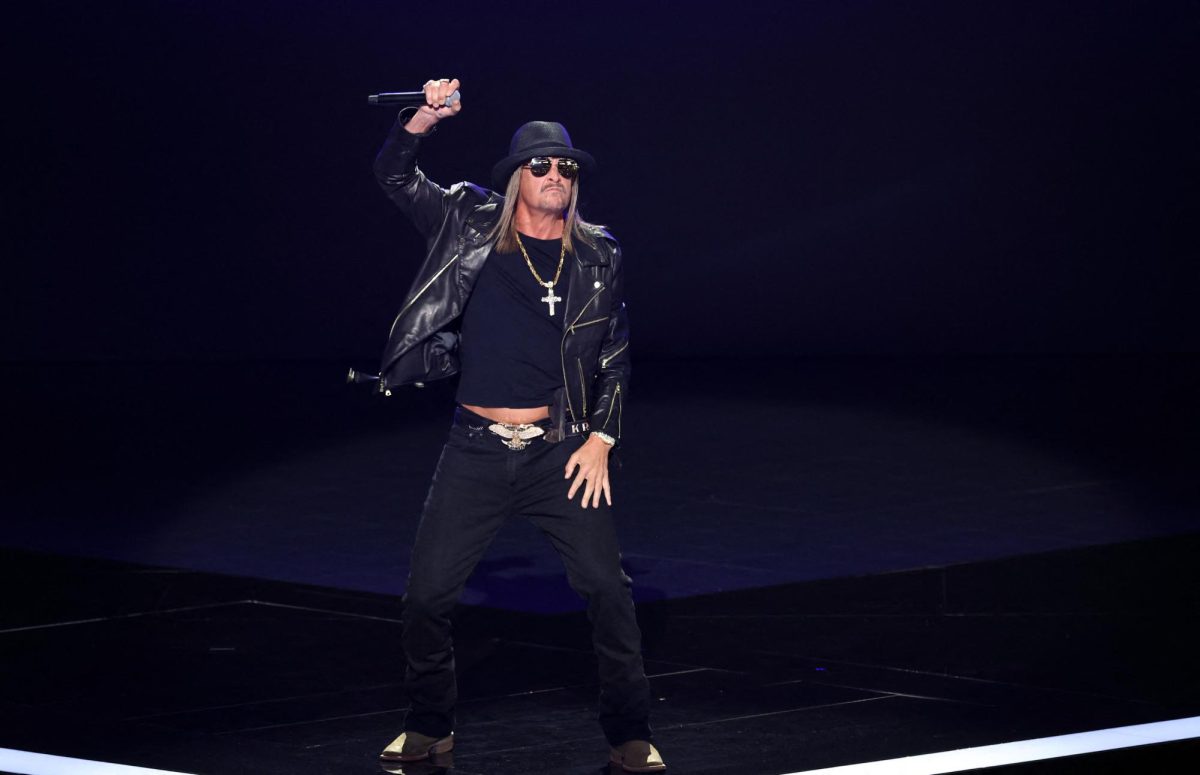

Anthony, played by Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, reaches for a mirror, but his reflection shows a hook hand similar to the one described in the Candyman legend.

The biggest departure “Candyman” makes from the original film is the absence of a strong lead villain. In the 1992 film, Tony Todd’s Candyman was a looming presence over the narrative. His gravelly voice and towering frame made him a horror icon. A lesser filmmaker might have tried to replicate this presence with a new actor stepping into Todd’s shoes.

Instead, director Nia DaCosta and writers Jordan Peele and Win Rosenfeld choose to focus on the generational horror of the Candyman legend. Here, Candyman is an idea — not a single entity, but something far greater that lurks in cosmic space, waiting for its next host. It infects victim after victim over time, who each go on to commit their own acts of carnage as Candyman.

“Candyman isn’t a he,” a character says to Anthony. “Candyman’s the whole damn hive.”

That’s not to say the lack of a singular slasher villain deprives the film of the gory touches of the original.

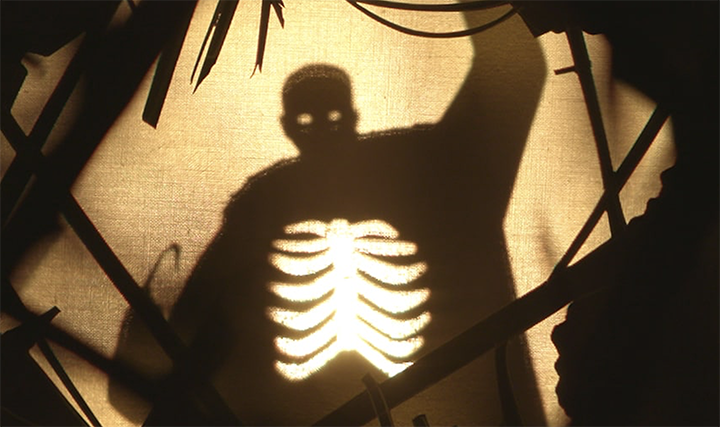

The kills here are expertly crafted. DaCosta makes use of the visual calling cards of Candyman lore — bees, candy, mirrors. Playing with the latter in particular gives the film some of its most visually inventive moments, with Candyman seen through reflections only as its grisly violence is acted out on the real world.

While the original film dealt with the violence of white supremacy in the past and its effects on the present, the sequel explores how this original violence is still happening in a very direct way, and how that violence can change course. How it goes about conveying this — specifically, the ending — lacks the subtlety that made the original effective, but still packs a heavy punch.

In some ways, the storyline of the sequel surpasses that of the original. Candyman is based on a Clive Barker short story, and like 1987’s “Hellraiser” — another Barker adaptation —the original film suffers from a distracted execution of a great idea.

Here, however, the idea is fully realized, even subverted.

By telling the story from the perspective of a Black man, the effects of the Candyman legend feel more direct and focused. Anthony begins as another person caught in the snare of the Candyman legend. By the time the film ends, he’s become something else entirely.