Native American employees share personal stories

Jose Romero

editor-in-chief

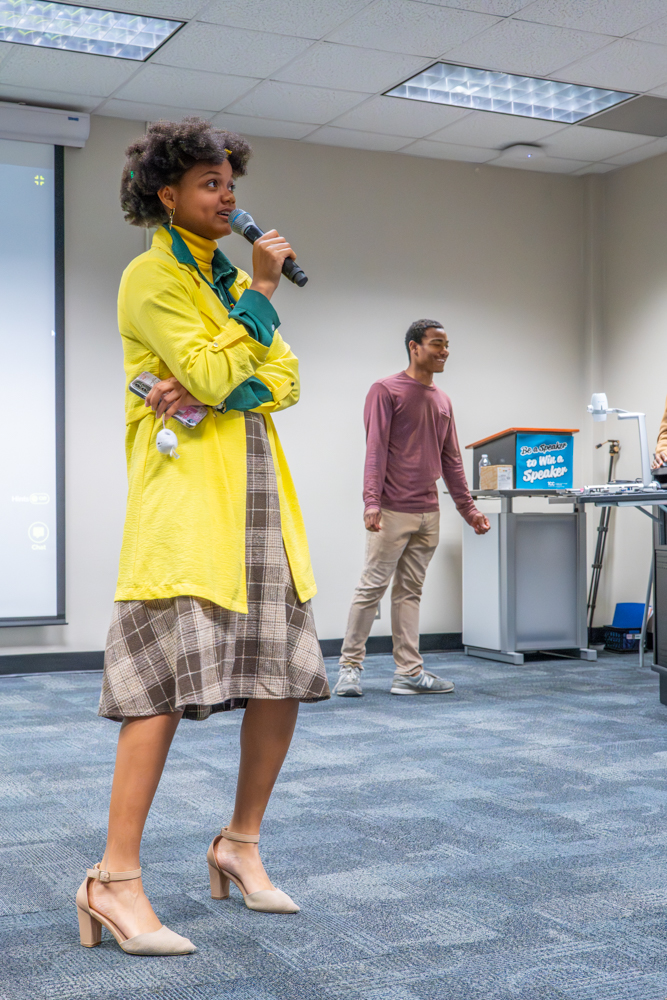

Marjeanna Burge’s grandfather was raised at a time when his heritage was shunned, forcing him to repress it and assimilate. But Burge’s grandmother ensured her culture wouldn’t be lost, allowing Burge to wear it like a badge of honor.

Burge is the NE intercultural network coordinator, and she is a citizen of the Comanche Nation.

This month is Native American Heritage Month, so two TCC employees from different

indigenous tribes shared their experience being a part of the community and how it has

shaped them.

Growing up, Burge wasn’t taught too much about her culture. Her quest for self discovery began once her mentor asked her what it meant to be a citizen of the Comanche Nation. She didn’t have an immediate answer, but she wanted to have one, so when she got her associate degree, she moved to Kansas and attended Haskell Indian Nations University. Afterward, she went to Kansas University and got her master’s in Global Indigenous Nations Studies. Currently, she’s working toward receiving her doctorate in sociology, and she plans to write her dissertation on Comanche tribal members.

“I was raised by my grandparents and my grandfather was full-blood Comanche,” Burge said. “My grandmother was white, but she was fascinated with the culture, so she’s probably the one that kept us connected to it in some ways.”

Burge’s grandfather went to Fort Sill Indian School in Oklahoma. It was a boarding school where Native Americans were forced to convert into European-American culture. Her grandfather’s sister told Burge stories of how they were treated in these schools, whipped if they spoke a bit of Comanche.

“He taught us probably about five words when I was a little girl, and I’ve never forgotten them,” Burge said. “But, he wouldn’t teach us the language. He would say, ‘Oh no, you need to learn English, and you need to just go to school and get a job’ and all that stuff.”

Now that she’s an adult, she has spent more time reflecting on why her grandfather may have kept his culture so hidden. Burge believes that he may have been ashamed of it since it was forcefully taken from him. But, even with all this adversity, she said he was still proud to be Native American. He was a quiet man, but he offered her glimpses of the

things he loved about the culture and people.

Burge said media and education are stuck in the past when it comes to representing Native Americans. In doing so, it makes the community seem like mythical beings that don’t exist anymore, she said.

“I’ve heard stories recently that some young person did not think that there were any Native Americans still alive,” she said.

“Reservation Dogs” is the first show to have a fully indigenous crew of directors, writers and series regulars. Burge said it presents hope for the community.

NE government professor Lisa Uhlir is Ojibwa, and she said the small population of Native Americans could potentially be the reason for the lack of representation. At TCC,

Uhlir said she ensures there is representation by taking time during Native American Heritage Month to do various presentations, telling stories about her people.

“Having those opportunities to sort of let people know that we’re still here, we still exist has been really valuable,” she said. “It’s one of the things I’m grateful for that they’ve done for us.”

On the topic of gratuity, Uhlir said what she has done to reclaim Thanksgiving, stripping it from its controversy. Instead of focusing on the negativity around it, she uses it as a connection to her historical past.

“I remember growing up, one of my father’s favorite things was whenever the

Redskins would beat the Cowboys,” Uhlir said. “That was his way of getting back for Little Bighorn.”

She said Thanksgiving is Native Americans’ holiday. It represents how her culture is all about helping others and how they’re willing to give more than they had. By focusing too heavily on the history of the holiday, it could minimize the value of her culture and how Native Americans helped, Uhlir said.

Beneficial changes that can help the community need to be federal, she said.

More power to reservations to punish non-native criminals, better financial and technological resources and a better curriculum for higher education for Native American students are a couple of changes she thinks could assist the community.

“Educating native students often require an understanding that we think in a different way,” she said. “We don’t think linearly, and we don’t think in the scientific method way. Requiring us to change creates internal dissonance.”

After Thanksgiving break, Uhlir will be doing a presentation on Native

American creations that people don’t realize were made by them. In past years, her presentations were more focused on historical tragedies, so she wanted to take a different approach this year.

“In the way the world is right now, it really would be a ray of sunshine to focus on positive things,” Uhlir said. “I want to be proud of my people. I want to be standing on the rooftops shouting how wonderful they are.”