By Kathryn Kelman/editor-in-chief

A student writes something concerning in a class assignment, such as revealing a desire to cause harm to themselves or others. What is the appropriate response? At TCC, the student’s instructor would notify TCC’s CARE teams who then conduct a threat assessment and create a plan of action for getting the student the help needed.

But a comment in a class assignment isn’t the only red flag faculty and staff are trained to look for that signal a student in distress.

Sudden changes in behavior, like changes in attendance or being more antagonistic, are also things TCC personnel are trained to look out for, said NW English instructor Theresa Heflin.

Heflin has worked with TCC’s CARE teams at least 10 times since they were introduced to her campus in 2013. In fact, she sent a report on a student to NW’s CARE team just last month.

“They’ve been fantastic and supportive,” she said. “We can turn our concerns over to them, and since we’re not counselors, it gives the students more options for help.”

All five of TCC’s physical campuses have a team that meets weekly, and the college is also currently working on putting one together for TCC Connect.

CARE teams, also known as behavioral intervention teams, are a cross section of representatives from different areas on campus to support students, faculty, staff and administration through an established protocol, according to the National Behavioral Intervention Team Association’s website.

NW student development services vice president Joe Rode said TCC’s campus CARE teams are one measure to mitigate the risks of incidents, like the February school shooting in Parkland, Florida, from occurring on one of TCC’s campuses.

TCC adopted the CARE acronym over the BIT acronym because they didn’t want it to be “punitive,” Rode said.

The CARE acronym stands for consultation, assessment, resources and education, all of which are functions of the teams.

“The number one way to prevent an active shooter is by proactively helping students and talking to them,” Rode said.

The teams use NABITA’s threat assessment, which goes over behaviors and offers remedies and solutions to aid students, South student support coordinator Belinda Lopez said, adding that the assessment also ranks students by a color. Red stands for extreme risk, orange for severe, yellow for elevated, light green for moderate and green for mild.

Anyone can report a student online by going to http://tccd.edu/care, which takes a person directly to the reporting form.

The teams don’t only look at students who pose a threat to themselves or others. They also work with students struggling with homelessness, domestic violence, financial crises and more, said SE student support coordinator Vekeisha Baker.

Once a student has been referred, the teams are alerted and then determine the level of urgency using the threat assessment.

“If it is urgent, we can call an emergency meeting or email to come up with an action plan,” Lopez said. “If it’s not urgent, then we can wait to do that at our weekly meeting and potentially follow up with the person who submitted the report.”

As NW’s student development services vice president, Rode serves on the campus’ CARE team as a co-chair and helps manage the referrals the team receives. He was also a member of the initial task force that developed TCC’s first CARE Team.

The teams comprise eight individuals from student support services, campus police, advising and counseling, health services, academic affairs, student accessibility resources, student life, and student conduct and Title IX.

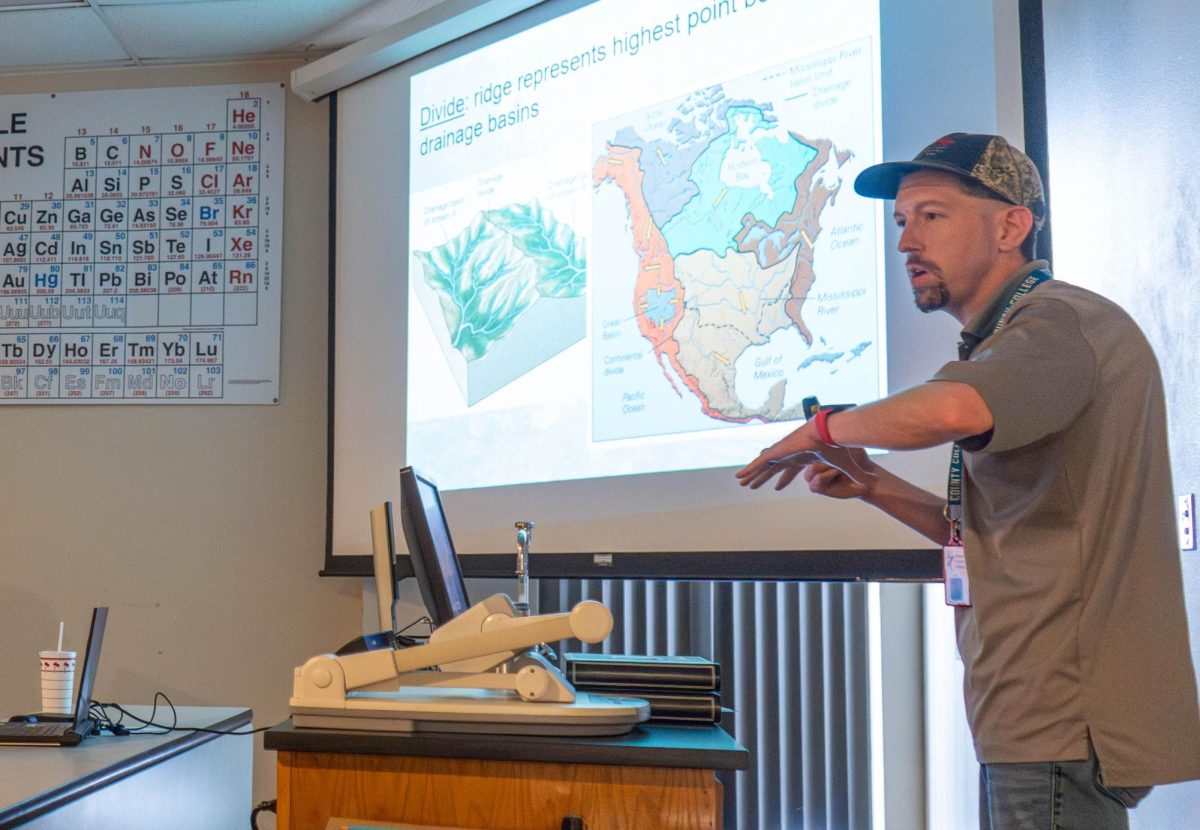

Collegian file photo

“The national association of behavioral intervention recommended the teams be comprised of people with different skills so they can get a variety of eyes on students,” Rode said.

Baker said students do not sit on the CARE team.

“Because of the nature of the concerns that are brought to us, we want to protect the identity of those students and what they’re going through,” she said.

BIT teams grew in popularity at colleges and universities following the Virginia Tech massacre on April 16, 2007, during which 32 people were killed and 17 were injured before the shooter committed suicide.

TCC introduced its first team to the college in 2011 after former TR student development services vice president Adrian Rodriguez joined the district in 2009 and noted the college didn’t have one.

After receiving support from administration, Rodriguez assembled a task force to evaluate the BIT teams at other higher education institutions. Following extensive research and training, the first team was implemented.

“The teams take a proactive and preventative approach by providing assistance to students who may be in distress through consultation with concerned faculty, staff and students,” Rode said. “They also communicate consistently between departments and other campuses and provide referrals to on- and off-campus resources.”

The FBI considers BIT teams to be the gold standard for keeping students and campus communities safe as the teams are proactive rather than reactive like the officers sent in after an incident has already taken place, Rode said.

South student development services vice president Larry Rideaux said the teams are in place to keep students from falling through the cracks.

“We don’t believe in throwing students away,” he said. “We believe we should provide the support to help them be successful and accomplish their goals.”

The teams address the issue internally or externally depending on the needs of the student, Rideaux said.

“We make it a point to refer students to needs outside of TCC when necessary such as the food bank,” he said.

Many reports the teams receive focus more on the CARE aspects rather than the behavioral intervention aspect of the team, said TR student support coordinator Tim Cason.

“It happens, but more often than not we see students in distress and serve almost like a social worker,” he said.

TCC has seen an increase in referrals this academic year, which has been the trend for the last few years, Cason said.

From Aug. 1, 2016 to July 31, 2017, 280 referrals were made around the district. From Aug. 1, 2017 to March 2018, 350 referrals had already been made districtwide, Cason said.

He said the increase is “wonderful” and doesn’t mean TCC has more students of concern.

“It means we’ve done a better job educating the community,” Cason said.

Rode said he thinks it could be a combination of both the teams’ increase in education efforts and an increase in students in distress.

“The more referrals the better, though,” Rode said. “The last thing we want to do is ignore students struggling.”

The increase could also be due to the number of mass shootings that have taken place in the past year, but they don’t know for sure, Cason said.

The teams’ efforts to point people toward the resources they offer play a role in the increase as does the growing national attention to mental health and school safety, but “that’s only one piece of the pie,” Cason said.

“We do see a surge in police reports and mental health referrals when incidents like that happen, but I personally chalk it up to the work we’ve done education- and outreach-wise,” he said.

Due to the confidentiality of the cases, students could not be reached for comment, but both Rode and Minor said students are appreciative of the assistance the teams provide. Lopez said the teams have received feedback from students thanking them.

The teams have also been praised by faculty and staff for the work they do. SE English instructor Emily Taylor-Gaulding said the teams are great and really come in handy for getting students in touch with other resources.

“Sometimes, it’s difficult for us to address outside of class stuff without a very direct confrontational feel,” she said. “The teams help smooth that over.”

Taylor-Gaulding said she hasn’t submitted any referrals yet this year but appreciates how well the teams keep them in the loop.

“I’m comforted knowing they’re [the students] talking to someone,” she said. “I’ve gone to them [the CARE team] on a couple of occasions when I wasn’t sure I should and that’s been really great too because I know they’re going to look at a problem regardless of urgency.”

It’s easy for people who report incidents to feel like they’re overworrying at times, she said, but the teams do a good job of reassuring them that it’s OK to bring up concerns they have and that they should.

TR reading associate professor Christi BlueFeather said in today’s climate, more help is good.

“Many students in high-stress situations will ask for help,” she said. “The CARE teams are my go to place, and I tell my colleagues as well.”

Though they don’t know the end result after reporting a student, BlueFeather said she is confident in the process.

“You have to trust the process is taking place,” she said.

She recommends that if anyone is ever in question of whether a student may need help or have any kind of feeling that they do, people should report it.

The focus of the CARE teams is on the students, said Rode, who hopes to improve student retention by developing relationships with those who are at risk. He added that providing a “culture of caring” for students is vital.

“We have incredibly skilled people on our CARE team and have built a solid network of resources for referrals,” he said. “It’s amazing how effective CARE teams are on campus, and institutions that don’t have BITs must rethink that.”