By Martin Ramirez/ south news editor

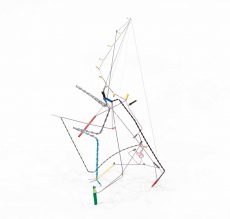

South had three new pieces of art installed on various walls on campus last month by Max Van Pelt.

Van Pelt is a painter, sculptor and installation artist. Art assistant professor Joshua Goode invited him to visit South, create a one-of-a-kind piece of art for the campus and talk to classes about his experience. Van Pelt arrived and chose an area he thought was best.

“In my visual work, I make sculptures, mixed-media paintings on paper and hybrid installations. I use a lot of different materials and techniques in my work,” he said. “Each piece is a deliberate act of drawing, marking the transition from nascent ideas that exist in the mind toward those that exist in sympathetic resonance with their surrounding spaces.”

The sculptures he formed on South are located on three different walls. Two installations are in the left hallway of the Recital Building near the art studio. The other is situated on a high wall in the Performing Arts Center on the left toward the gallery.

“I call them elements. They’re fragments of sculptures,” he said. “The sculptures are born from very simple urges to connect one or two materials, or maybe it is an idea about a color or a certain way of bending something. And then they spend long periods of time as incomplete fragments that I am not sure what do with until one day I will put two of those fragments together and see another idea.”

Growing up in Boulder, Colorado, Van Pelt practiced competitive Olympic-style target archery until he left for college.

“I think it taught me a lot about how to focus in my field of awareness onto minute details and become sensitive to very subtle variations in things,” he said. “It also made me comfortable with being patient and sticking at something for a long period of time, often with results that revealed themselves more slowly or not at all.”

Creating model airplanes in high school also helped his talent as an artist.

“For me, it was my first major experience working with my hands and learning about craft,” he said. “But there’s also this participatory quality. Not only were these formally beautiful objects, but they could also be turned around and engaged with by flying them through the air, crashing them and rebuilding. And I experience a very similar excitement with making artwork.”

As an avid whitewater kayaker, Van Pelt learned as much from close time spent with friends as he did in class.

“When you’re down low in the kayak, you can’t see very much,” he said. “You have to take in this constantly changing field of information — the horizon of moving water ahead of you — and then hone in on very subtle observations to ultimately determine the best way through. And I find that incredibly analogous to the sort of perception/attention that I’m trying to achieve in the studio every day.”

When he began classes at Dartmouth College, he took an art history course about modern architecture. This class introduced him to new inspirations and changed his artistic style.

“I started to learn about these incredible modernist architects like Louis Kahn and Carlo Scarpa,” he said. “These architects were incredibly sensitive to the way in which physical details affect people’s lives, and I think I was inherently drawn to that.”

Van Pelt began to look at drawings these architects had made while designing buildings. Then, an idea struck him. He used a projector to shine an image of Scarpa’s Castelvecchio Museum onto his paper and drew various lines, texture and shapes to start his drawing.

“And then I turned off the projector and started to investigate those marks, connecting them, adding to them and responding with my own subtle inclinations,” he said. “It’s a process that has guided almost every large piece I’ve made since.”

Van Pelt graduated summa cum laude in 2011 as a studio art major with a concentration in architecture. Then in the fall of 2012, he moved to Providence, Rhode Island, and set up a studio.

“I think creative work in the studio is so much about learning to follow your instincts during periods of being vastly uncertain. For me, it’s so much more about the unanticipated insights that crop up than it ever is about executing a vision. In addition, I can’t overstate how much more often I encounter inspiration in the middle of the work when my hands are moving than I ever do beforehand.”

He also offered advice to the class.

“I think it’s really worth taking the risk to push something beyond your knowledge of where you think it’s going to go,” he said. “Don’t be afraid to take a painting too far or push a sculpture to the point where it might totally fall apart. Because often when it does, it comes out better than you could have ever imagined.”