By Shelly Williams/editor in chief

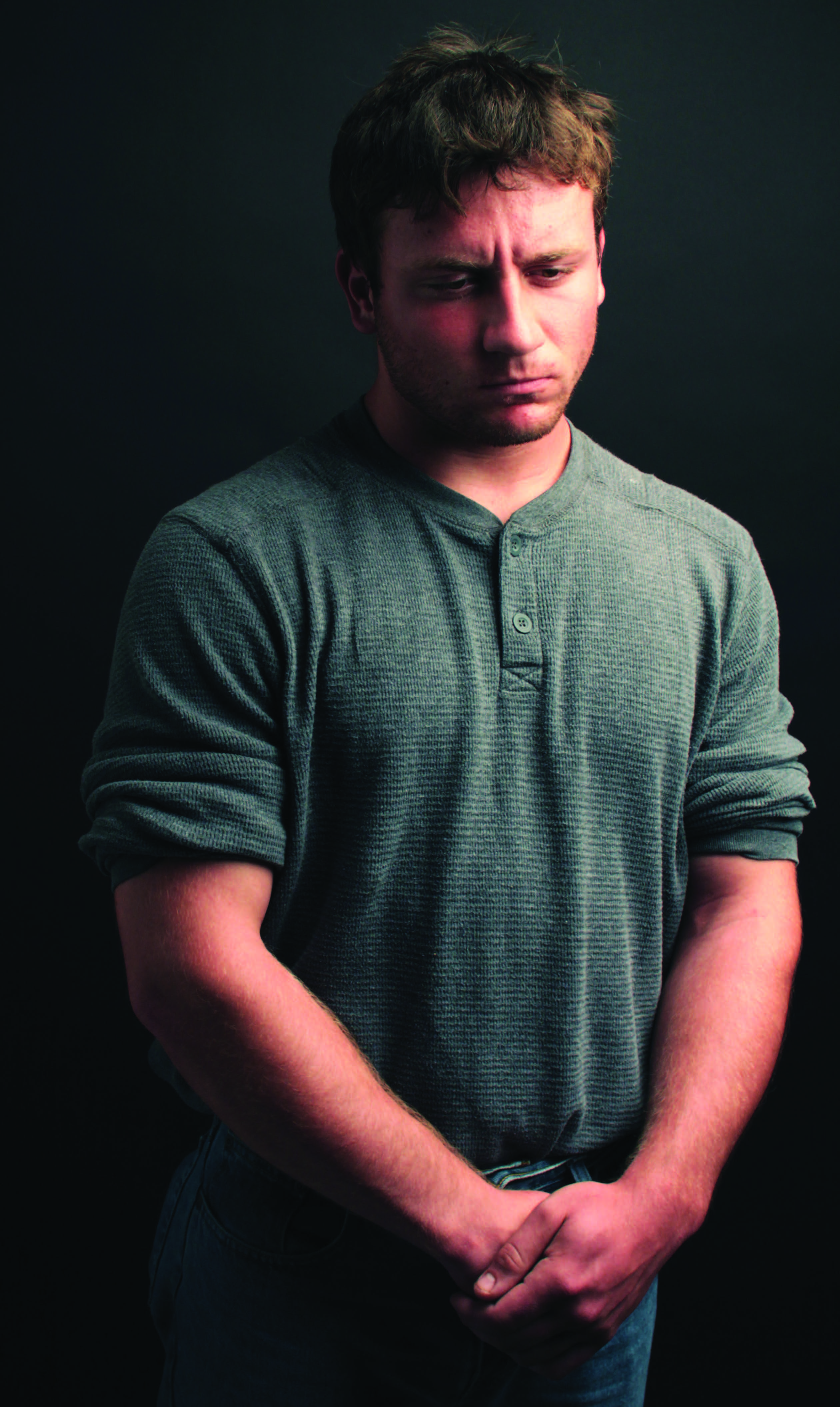

He sits at a table, fidgeting as he relives the sickness that drowned his body two years ago. He isn’t sure he’d be here if he’d given into it.

“Limits are defined by you and you alone,” said 20-year-old Jason Cates.

Before the NE Campus student and nursing major graduated high school, his body began to fail him. In March 2008, doctors diagnosed him with testicular cancer. But months before his diagnosis, Cates suffered from a different illness.

“Cancer sometimes brings up mysterious illnesses — illnesses that aren’t really explained,” he said.

A condition called costochrondritis held his lungs captive.

“It often brings the patient to see a physician or visit the ER because of the fear it represents a heart attack,” NE director of health sciences Dr. Woody Kageler said. “Costochronditis usually has no apparent cause.”

Kageler said the illness is an inflammation where the upper ribs join with cartilage that holds them to the breastbone or sternum. He said it’s more common in women and individuals over 40, but it can occur at any age

“It made it hard for me to breathe, and that’s when flags started to be raised,” he said.

That’s when Cates began asking questions.

A few nights before his diagnosis, Cates noticed one of his testicles was abnormally large. He soon visited the doctor, only to have his concern increase.

“It was really a sobering moment because he checked it twice and just sat there,” he said. “And then he said, ‘This isn’t good.’ That’s when I started to get really afraid.”

Testicular cancer forms in tissues of the testis and usually occurs in men between 15 and 34, but may occur at any age, Kageler said. According to the National Cancer Institute, an average of 8,000 new cases and 390 deaths occur from the cancer in the U.S. each year.

“However, it accounts for only about 1 percent of

cancers in males,” Kageler said. “Regular testicular self-examinations can help identify growths early when the chance for successful treatment of testicular cancer is highest.”

After his diagnosis, Cates said he began to crumble. Depression, an experience he’d already gone through before, and suicidal thoughts seeped into his mind.

“Years earlier, I had gone through a suicide clinic, trying to get over my depression,” he said. “But my suicidal thoughts came back because my grandfather had esophageal cancer, and I was raised without a dad, so he was my only father. So that [the cancer] brought up remnants of the pain I went through with him dying.”

Lost in his own instability, Cates grew more afraid for his life with the knowledge that the cancer could spread quickly. However, his family scheduled to have the cancer removed as soon as possible.

In April 2008, Cates went under the knife for the first of two surgeries. Surgeons removed the cancerous testicle, but after further testing, doctors discovered the cancer had spread to his lymphatic system, which helps protect the body against viruses and bacteria that invade the body.

“A lot of people have a fear of different things. My fear was the fear of the unknown and not knowing how far it had progressed,” he said.

At this point, Cates said he was emotionally compromised. He missed school because he couldn’t cope with it.

“I wanted to live so badly,” he said. “I was only 18. I didn’t want to have to ever go through the pain. I just wanted it over with.”

About three weeks after his high school graduation in June 2008, Cates underwent his second operation.

Surgeons sliced from the middle of his chest to his lower abdomen. He said doctors informed him they weren’t sure where the cancer was and would have to search his body to find it.

“But the doctor was extremely optimistic and didn’t fill me in on details until afterward,” he said. “He didn’t want to discourage me while there was still a chance.”

With 56 stitches and 14 titanium staples in his skin after the surgery, his body was a wreck. That’s when Cates said he hit rock bottom.

“At that point, I was about ready to give up because I didn’t know where it was going to go from here,” he said. “I felt as though it was basically one big trial and error.”

During the recovery process, Cates could see the pain around him. As he drifted in and out of consciousness, tears from his family forced Cates to face his choices.

“What hurt me the most was seeing my mom cry,” he said. “My mom basically raised me until my stepdad came along. Both of them really mean the world to me and to see them really both cry, it really hit me hard.

“That’s when I realized I can’t leave these people behind. I just can’t.”

Cates said his family even now is not ready to talk about his battle with cancer and that the subject is still sensitive.

Doctors said it would take two weeks for Cates to recover, but he did it in four days. Two days after his operation, Cates said he forced himself out of bed despite the searing pain from his stitches and staples. Another two days, and he was free of the machines his body was hooked up to.

Now Cates has been in remission from his cancer for almost two years and is working his way into the nursing field. During his stint in the hospital, Cates said his family couldn’t visit all the time. That’s when he said the nurses became his family.

“That made me interested in being there for other cancer patients who are in the same kind of situation,” he said.

Cates said it pains him to see those in similar situations give up. He wants to return the hope the nurses gave him for fellow cancer patients. He said when people begin to believe they’re against the odds, they’re setting themselves up for failure.

“That’s what I did — I was setting myself up for failure,” he said. “But I feel I was put on this earth to make people better, to make people happy. I want to return that to each and every one of these people.

“When people say, ‘Sky’s the limit,’ it’s a lie that society has taught. Go into the heavens, wherever you want to go. You just have to have the drive and the commitment to go there.”