OLLA MOKHTAR

campus editor

olla.mokhtar@my.tccd.edu

What ailed NE student Haley Southers’s family is the reason she’s at TCC.

Depression, anxiety, substance abuse and bipolar disorder affected her family in the ‘80s and ‘90s where mental health wasn’t talked about much, Southers said.

Seeing this growing up made her want to obtain a license for chemical dependency counseling and with it came the class called Ethics for Social Work.

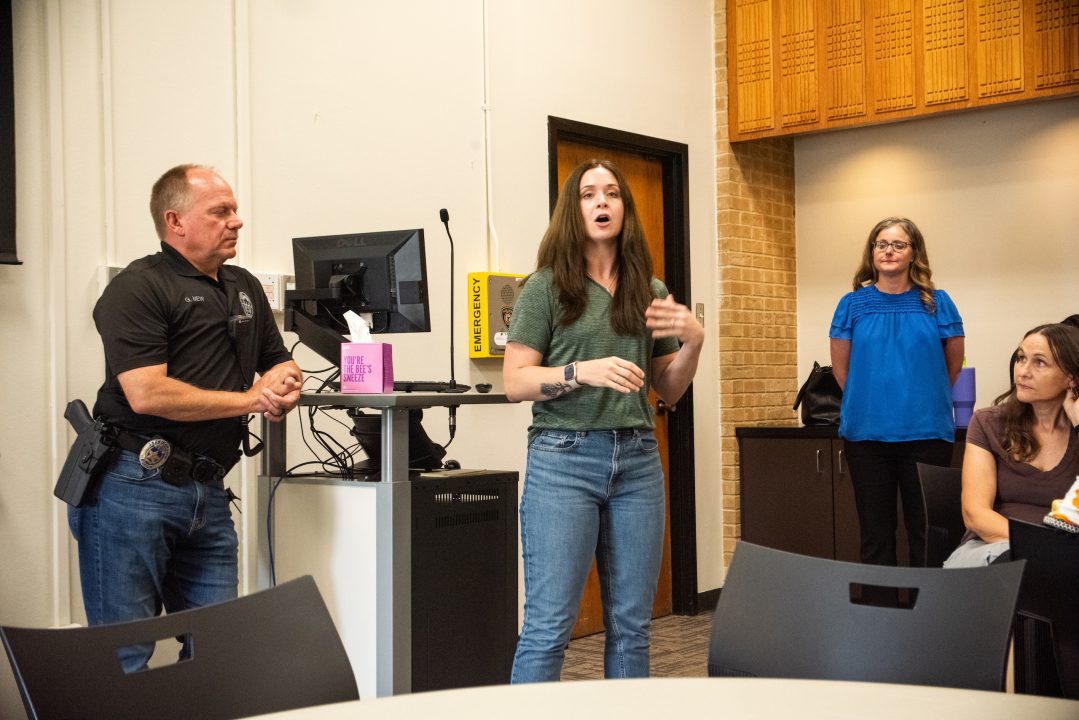

She, along with a group of classmates and a number of NE’s mental health personnel, had the opportunity to listen to the Grand Prairie Police Department’s Crisis Support Unit on NE April 17. In a presentation, the unit educated the students and department of mental health personnel about the ties between mental health and police work. How they make it work to slowly eliminate further violent escalation, especially with mental health crises, being the center of it.

The goal — reduce the stigma of mental health, the fear of law enforcement and provide a response and follow up to those in need.

Victor Allen, the professor of Southers’s class, said he organized the presentation to let his students and fellow personnel know that this type of program exists.

He also said that as a veteran, his community is often misunderstood. Allen hopes that after the presentation people know to notify the police, should they be contacted, of any mental health challenges a person may have history with.

He is hopeful the next generation of social workers, or maybe even his students can take that into play.

“Destiny is not an accident, and my students bring up very thought-provoking topics, which makes you want to take academia to a higher level by being more creative in your teachings and exposing them to arenas that they probably would have never encountered,” Allen said. “So, they can go ahead and pass the baton to future generations.”

The crisis support unit is made up of three co-responder teams. They partner a master’s level licensed mental health professional with a specially trained and law enforcement certified mental health peace officer. Together they ride patrol vehicles to assist in a number of ways, including responding to calls about individuals who are experiencing mental health crises.

This is something Southers is definitely interested in, she said. In fact, she is especially glad she can become a part of a new generation of social workers that can change the stigma around mental health.

“It feels really good, it’s really rewarding,” Southers said. “Even though I’m just getting into it. It still feels good to know at some point I’m going to be able to give other people the kind of help and resources that some of my family members weren’t able to get or just weren’t willing to accept.”

When Greg New, a crisis support officer, first started working as a police officer 35 years ago, he said mental health wasn’t really talked about in the police community. Back then it was an assumption that a person was simply disgruntled. New said that the space around mental health is better now that training is mandated for new police officers.

“Younger officers are seeing something and being able to change some of their perspectives on what’s going on. I think it’s a better change for the future,” New said.

Though there is a disparity in this field, New is hopeful that with more training and the help of the public it is possible to fill it. Currently more police departments are recognizing this and implementing it in their respective cities, he said. They are also beginning to recognize how educating the officers in mental health and dealing with their own can make them better equipped for the public.

“It’s also recognizing changing the eyes of a long generations worth of the way we do things,” New said.

Before, if a person was in a manic stage he would probably see them as more aggressive and not realize that they were having a mental health crisis. Now he recognizes some of that, learned to slow down, take a step back and maybe learn to deescalate and then try to start working on them.

“We’re always going to make mistakes because we’re human. It’s how can we minimize those mistakes,” New said.