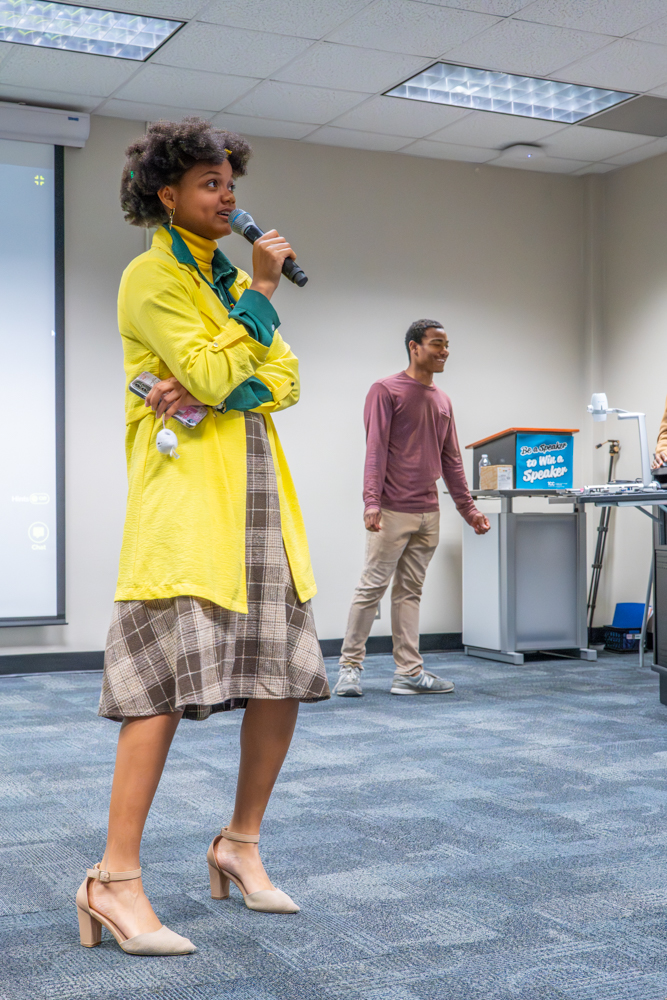

By Ashley Bradley/ne news editor

Steven Branfman showed a group of students techniques of the Japanese style pottery called Raku by throwing, glazing and firing his own work.As Branfman sat spinning his work on the ceramics wheel, he told the class during the Sept. 11 workshop on NE Campus some of the techniques he uses for making his art.“It’s all about feeling as you go along. Nothing is automatic,” he said.

Although the students were quiet, they all seemed to be in a good mood. Jokes were made as he used a sponge and his fingertips to make soft ridges in the clay.

“How many can you make in a day?” associate professor of art Karmien Bowman asked.

“Sitting making pottery all day? Oh, I don’t know, maybe six or seven,” he answered.

By the end of Friday, he had made eight.

Before the class went to check Branfman’s work in the kiln, a student asked how he responds to a request for a specific design.

“I’m not going to make something if I wouldn’t already make it myself. I’m not going to make something if it’s not my style,” he said. “If they like it, they can buy it. If not, it’s part of my artwork anyway. That way, everyone walks away friends.”

While Branfman left his work on the wheel to dry, the class made its way outside to see what the kiln had done to his work. He took tongs and pulled each item out revealing four pieces. The last one was the largest and fire red from the heat inside.

The artist controls the kiln, which can reach a temperature of 1,800 degrees, Branfman said.

“What happens if it’s not ready when you pull it out of the kiln?” a student asked.

“It’s like checking the cookies. If they aren’t done yet, just put them back,” said Bowman as Branfman laughed and agreed.

“That and experience will help,” he said. “After a while, it just becomes second nature to know when to take them out.”

After he pulled his pieces out of the kiln, he led the class back in to finish his other piece on the wheel.

He began talking about what to do to make each work specific and random, but Bowman said that’s not always easy to do.

“It’s really hard after many years to achieve random because you already know what’s going to happen,” Bowman said.

For Janice Bowman, no relation to Karmien, experience isn’t the problem. This semester, she enrolled in her first ceramics class.

“I haven’t ever thrown,” she said. “Just watching him gives me an idea of what I need to do.”

As an undergraduate, Branfman knew that he wanted to work with Raku pottery.

“It captured me because of its physical nature. Handling the hot pots interested me because with that kind of art you have to be in touch with it the entire time,” he said.

Although Branfman was already teaching Raku workshops near where he lives in Boston, he started to become more popular after his book was published in 1991 and was asked to teach in Europe.

“I knew I wanted to teach. Then I started doing it,” he said. “It wasn’t until later after the first book published that I started teaching around the world.”

On Saturday, participants of the workshop brought pieces of clay to make their own work based on Branfman’s style and technique.