By Cindy Reed/reporter

(Part two in a three-part series on the Sandwich Generation—when the role of a family member changes to accommodate children and elder parents.)

Waking up one day and realizing the parent-child roles have reversed, many adults may feel like Alice Through the Looking Glass.

Caught in the middle of a generational sandwich is often difficult although potentially rewarding.

Even under the best of circumstances, caregivers often find themselves burned out, mentally and

physically taxed beyond belief.

Zoran Basich, president of Nursing Home Solutions and leading expert in long-term and elder care, wrote an article for Today’s Senior Network (todaysseniornetwork.com).

“ Being a caregiver is a stressful responsibility that can lead to tension, migraine headaches, high blood pressure, asthma, nervous stomach, bowel problems and chronic lower back pains,” he said.

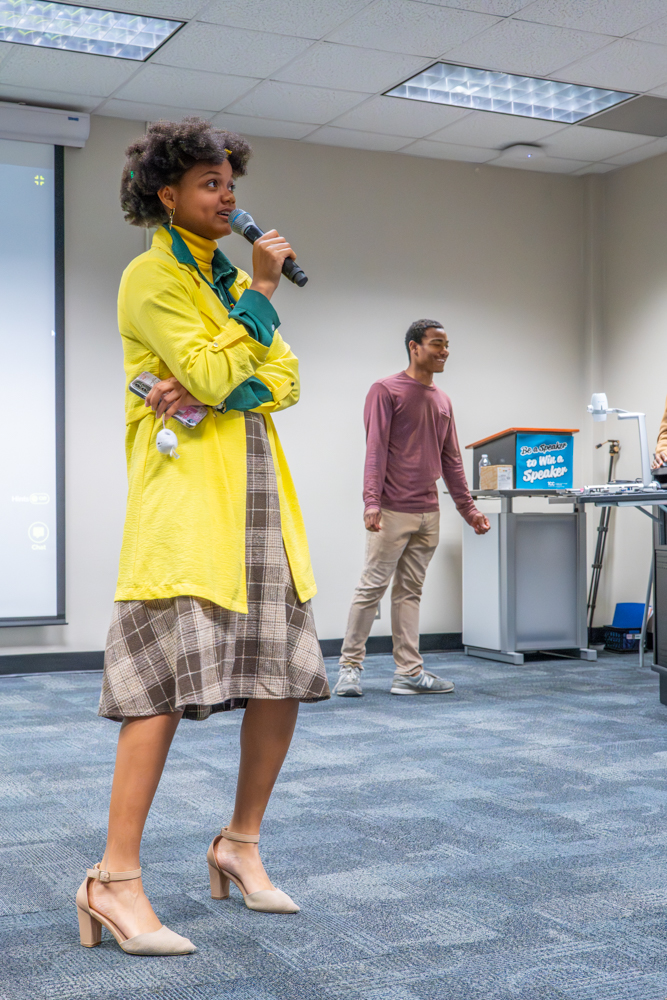

Kelley McAnally, NE Campus student and mother of a young child, helps care for her grandmother, mother and in-laws.

“ My in-laws did not save well,” she said, “neither did my grandparents.”

McAnally spends much of her free time taking care of their needs, running errands and chauffeuring them to appointments.

Some signs of caregiver burnout include irritability, fatigue, mood swings, snappishness or resentment toward the care-receiver, loss of sleep or restlessness, Basich said.

Those experiencing such symptoms should seek professional help, learn and use stress-reduction methods or find alternatives to the situation, including skilled nursing facilities.

Dr. Laura Overstreet, chair of the sociology/psychology department on NE Campus, said 60 to 70 percent of elder care is carried out in the home of and provided by family members, generally a female.

Shana Guzman, NE Campus student, is typical of the caregivers even though her mother was only 52 when she suffered a debilitating stroke.

Guzman went through a substantial amount of anger and resentment, which left her feeling guilty.

Guzman continues to care for her mother though her mother has returned to work as a stock clerk at a local Wal-Mart. Her mother’s speech limitations since her stroke have made it difficult for her to communicate with customers, so she works the midnight shift.

Meanwhile, Guzman has come to terms with their circumstances and has requested other members of the family chip in to relieve some of the financial burdens of caring for her mother.

Experts say the job is too stressful and strenuous for most people to remain full-time caregivers indefinitely.

When facing caregiver burnout, the individual should ask herself the following questions:

“ Is my caregiving doing more bad than good?”

“ Is my quality of life being compromised to the extent it is also compromising my care-receiver’s quality of life?”

“ Is it time to consider, and can I accept, an alternative care option?”

“ Do I know enough about the financial implications of putting my loved one in a skilled nursing home?”

Most caregivers need outside assistance. Nursing Home Solutions has pioneered the field of helping families wade through the legal and financial ramifications of putting a loved one into a skilled nursing facility.

Making such decisions is not easy.

A multi-site study by the University of Pittsburgh, published in the August 24, 2004, issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, indicates caregivers who institutionalized their loved ones do not experience relief, but rather suffer additional emotional trauma from their decision.

The study’s lead author Richard Schulz, Ph.D., professor of psychiatry and director of the Center for Social and Urban Research at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, said former caregivers continue to feel distressed because of their perception of their loved one’s decline and suffering, along with the new challenges such as frequent trips to the long-term facility.