By Kourtney Cribbs/reporter

In the corner of the Walsh Library on NW Campus stands a white cube large enough to hold a person. The sun shines through the large windows, casting a radiant glow on this window into an artist’s mind.

Eric McGehearty’s installment of “Doorway of Books” was made especially for the space, built with students and teachers. It even contains library books that were going out of circulation.

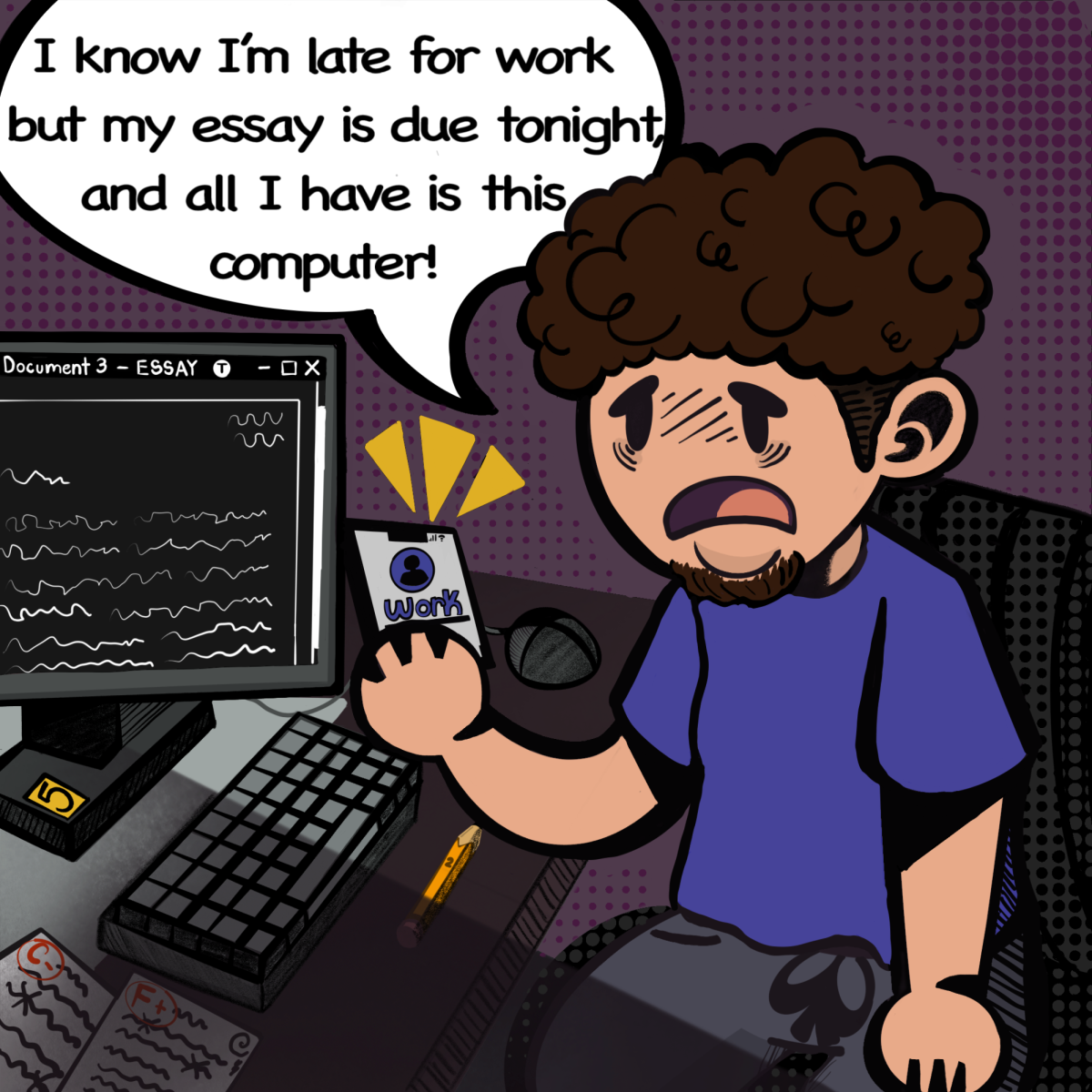

The doorway of the white cube is layered with books of all sizes and colors with one hole near the bottom of the stack. The hole was placed strategically to make the viewer uncomfortable as he or she stoops over to see what is inside. What the viewer will find is a white screen that plays shaky, unclear text that contains words like “dyslexia.”

The awkward position of the screen gives the feeling and emotion that McGehearty feels as a dyslexic.

Last Wednesday, McGehearty spoke to students and staff about his art and his struggles with the disability. Despite never reading a book in his entire life, McGehearty received his master’s degree in fine arts from the University of North Texas and taught at TCC and Dallas County Community College. After a few years of teaching college, he said he is much happier as a professional artist and consultant for the Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic, a nonprofit organization based in New Jersey.

McGehearty is an abstraction artist, meaning he starts with something real and then changes it. Many of his pieces are autobiographical and focus on one idea, primarily his perception of literature and how the mind deals with literature.

But this wasn’t always the case. During a graduate sculpture class, McGehearty said his frustration with his work became “dark and painful” and contained several ideas in one piece.

His professor found the work moving but said it lacked the personal touch and left the viewer uncertain about the message.

McGehearty did not tell people that he was dyslexic unless it was necessary. However, he confessed to his professor and was encouraged to use this struggle in his work. Working through his disability took more than a year, but finally the art made sense, he said.

“Art was always a safe place, but now that it had a reason and got more serious, now that I zoomed in on one idea, the work could speak volumes,” he said.

McGehearty’s work is relatable to all types of people. As an artist, he appealed to students like Amber O’Dell.

“I wanted to see him focus on something outside the box and not on the limitations,” she said. “I think he uses art as a barrier.

“I have a family member who is dyslexic. I think people can identify with him.”

Student Jerry Hartfield, who had a stroke and is now blind in one eye, said he was inspired by McGehearty’s accomplishments.

“I want to try something new and different now. I want to learn something new about me as a human,” he said.

As a consultant for the Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic, McGehearty has the opportunity to speak in schools about his art and about the non-profit organization that helped him.

“I really believe in what they do,” he said.

“Being successful in life is something they want kids to understand is attainable and let them know about the resources out there. We want kids to know you can be great. We give them the confidence and provide the tools.”

The children “get” his work, he said.

McGehearty said when he shows a piece to children, they shout out, “It’s about reading.” McGehearty encouraged students to pursue their excellence.

“Stop worrying about things you struggle with and turn something you’re good at into something your great at,” he said. “Let your will and desire show through — that’s when your life shines through.”

To see more of his work, visit McGehearty’s Web site or attend his one-man show at the McKinney Avenue Contemporary in November.

Anyone with a visual impairment or dyslexia can contact the Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic, which has been the leading accessible audio book library for students for the past 60 years, at www.rfbd.org.