By Linah Mohammad/ reporter

For years, the view from Hussein Abed’s classroom was the concrete wall that is the barrier in Jerusalem or, as the Palestinian refers to it, the “Apartheid wall.”

For years, Danielle Weitz would hide her real identity from others, afraid of their judgments because she was Jewish.

Though their lives on opposite sides of the Israel-Palestine divide may seem far too different, the SE students’ stories are nearly parallel.

Abed, born and raised in Beit Hanina, East Jerusalem, has suffered his entire life under Israeli occupation.

“A long time ago, you could tell the Israelis, ‘Go back where you came from!’ But nowadays, you can’t,” he said. “If you tell an Israeli this today, he’d say, ‘Go back where? I was born here.’ This is what makes getting rid of the occupation harder now.”

Weitz, on the other end of the spectrum, is a Messianic Jew. Her family had fled the persecution in Europe and came to the U.S. for refuge.

“Being a Jew is a part of who I am, my culture, my ethnicity. It’s a part of my life,” she said. “My parents would hide it because they would be bullied at school if they were found out to be Jewish. My dad would be called the ‘Christ killer’ and stuff like that.”

Weitz admitted there are times when she hides her Judaism, especially if she senses people’s hatred.

“When I serve a lot of Muslims, I make sure I’m not wearing anything. If I am wearing a Star of David necklace, I want to hide it,” she said. “Even though I don’t have a problem with them, I feel like they might have a problem with me if they knew I was Jewish.”

Our differences are creating this ridiculous hatred that shouldn’t exist. So many people are dying as a result of this, and it saddens me because there’s so many lost lives and for what?

Danielle Weitz

SE student

Weitz has said that she does this because she’s had bad experiences in the past regarding her identity.

“I remember when I would be really open about it and tell everyone, ‘Yeah, I’m a Jew,’ they would look down on me and criticize me,” she said. “They would ask if I hated Muslims or hated Arabs. They would just say hurtful things to me and treat me like I was below them, like I wasn’t equal to them. If I’m walking into a store and someone sees my Star of David, I feel like they give me cynical, judgmental looks. Sometimes, people would just cut in front of me.”

Linda D. Epstein/MCT

When making Arabic friends, Weitz is constantly afraid of their rejection because of her identity. Sometimes, she wonders if she should tell them she’s Jewish.

“The huge SE [Campus] Arab population intimidates me because I don’t know how they perceive me,” she said.

Although he is a Palestinian, Abed is very accepting of Jews.

“I don’t say that all Jews are bad. Many Jews are good people,” he said. “Generally speaking, the hardships Palestinians face are because of the Israeli government, not the people. I don’t see Jews as my enemies.”

Another one of Weitz’s struggles is merely watching the news.

“It’s hard for me to turn on the news and seeing what’s being broadcasted about Israel because the media shows a lot from the Arab side and not a lot from my side,” she said. “Like the last time [2014 Israel-Gaza Conflict], they showed Arab children crying and all the effects of that. It made it look like Israel was the enemy versus looking at it from an equal perspective. Both are wrong. This is equal.”

Oddly, according to Abed, almost all Arabs agree on the biases of the international media toward Jews and Israelis.

This is pretty much my life over there — a life of war, a life of constant occupation, humiliation and misery. My heart is dead, what do you want me to say?

Hussein Abed

SE student

“It hurts me. It hurts to see how hatred is so prevalent in our society. And how we can’t just be at peace with each other and how we think that violence is the only way to cure what’s going on,” Weitz said. “It’s very troubling. I try not to watch the news because it makes my blood boil.”

As a Jew, Weitz stands up for Israel. She is, however, against some of Israel’s policies.

“I am pro-Israel, but I can recognize the faults that Israel is still making,” Weitz said. “I also recognize the Palestinians’ right in the land. I just think they’re wrong that they don’t recognize Israel as a country and that they want to take over. I am not saying that Israel is perfect and Palestine is to blame at all. I do see faults on both sides, definitely. There’s hatred and violence on both sides.”

On the other side of the world, one of Abed’s struggles is the Israeli West Bank wall, which separated Abed’s family’s houses and made his life as a Palestinian in Israel harder.

“The wall was built in the middle of my aunts’ houses,” he said. “The sisters built their houses next to each other, but the wall separated them. If they want to visit each other now, it could take hours, and they have to go through multiple machsoms. It happened to a lot of families, not only mine.”

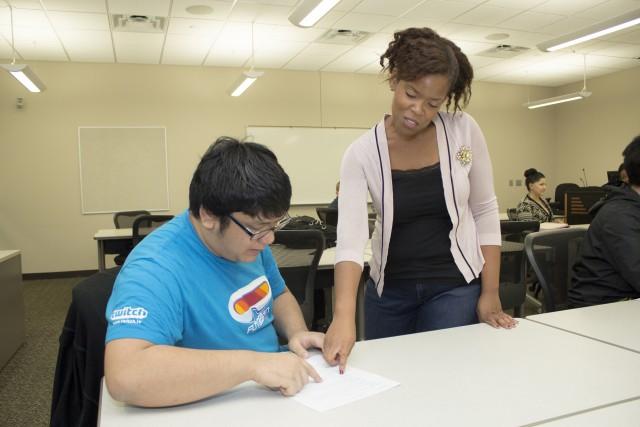

Katelyn Townsend/The Collegian

Machsom, the Hebrew word for checkpoints, is often used to refer to Israeli checkpoints, where they carefully inspect Palestinians passing through. The process can take hours.

“I get it because it’s [the wall] a protection method, but at the same time, it’s just more segregation, and it’s putting more strain on the fact that, ‘Oh, I am different from you, so I need to separate myself completely from you and not associate myself with you,’” Weitz said. “I have mixed feelings about it. I don’t think it’s going to solve anything in the long run. It’s going to create more of that feeling that we’re opposite, we clash, we hate each other.”

Before the wall, Abed’s school used to be really close to his house in Jerusalem.

“It was five minutes away,” he said. “After the wall was built, it started to take us anywhere from two to four hours. Sometimes, I’d get to school, and it’s already the second period.”

According to Abed, the inspecting process can be thorough or superficial, depending on how bad the conflict is.

“It is up to them. Sometimes they make it really hard for us,” he said. “It also depends if people are throwing rocks at them or not. They detain people for hours. They strip-search them, all sorts of things.”

For Abed, going back home after school was long and trying. Some days, Israeli soldiers would fire tear gas. He’d come home with teary eyes.

A lot of Palestinians try to jump this wall, but, according to Abed, they get caught. Then, they’re either shot or detained for a couple of hours.

“They’re then thrown back into the Palestinian side,” he said. “This wall has turned the West Bank into a cage, where they throw ‘the animals,’ as they call us Palestinians.”

People of the West Bank are trapped inside the wall. To leave, they need a visa or a permit, which are both hard to obtain.

“I see the West Bank as a big prison,” Abed said. “I feel crammed whenever I go over there.”

According to Abed, there is a clear distinction of Israeli neighborhoods and Arabic neighborhoods — the two rarely mix. The town of Beit Hanina, an Arabic town, is surrounded by a few Israeli settlements, French Hill, Pisgat Ze’ev and Neve Yaakov.

“Because of its location, Beit Hanina has become really dangerous. A lot of kidnapping is going on,” Abed said. “Kids are being kidnapped from our front door.”

Abed’s family owns a store in East Jerusalem’s old souk, or market. According to him, it’s not frequently visited anymore because tourists head to the modern Israeli malls. Many protests also break out there.

“Whenever a protest begins in the old souk, the Israeli forces attack the protesters with giant horses, sound bombs and tear gas,” he said. “They attack everybody in the souk, left and right.”

According to the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Israel since 1967 has demolished around 2,000 Palestinian houses in East Jerusalem for being built without permits, which are hard to get.

“I am definitely not pro any of that,” Weitz said. “I think all these cries for help, all these quick fixes are just going to create more problems in the future.”

Abed’s friend’s house was bulldozed for having a balcony built without a permit.

“The Israelis came to their house at 4 a.m. and told them they had to evacuate the house because they were going to destroy it,” he said. “I remember the following morning was crazy. The army came in with helicopters and armored vehicles. There were huge clashes and random arrests. At last, they bombed the house. They couldn’t bulldoze it.”

No compensation was ever paid.

“This is pretty much my life over there — a life of war, a life of constant occupation, humiliation and misery,” Abed said. “My heart is dead, what do you want me to say?”

Weitz contemplated her life and Abed’s.

“Our differences are creating this ridiculous hatred that shouldn’t exist,” Weitz said. “So many people are dying as a result of this, and it saddens me because there’s so many lost lives and for what?”