Over the last decade, mass shootings have become the new normal. President Obama said in a press conference after the recent shooting in Oregon that the response and media coverage have become typical and in ways make the situation worse.

But as media have adapted to a style of reporting on mass shootings, one thing that deserves to be re-examined is how many times the name and face of the shooter are splashed across the screen.

Of all the multi-day coverage these stories garner, the media do a great job painting a vivid portrait of the mass murderer but more often than not fall short painting a picture of victims’ lives.

Whether they speak to the shooter’s family members, friends, surrounding community or co-workers, viewers often end up with a better sense of who the shooter was than the actual victims.

To help remedy this, the parents of an Aurora, Colorado, theater shooting victim started a movement. Caren and Tom Teves, founders of No Notoriety, are asking reporters to limit the number of times the shooter is named in any one story and editors to consider how they use the shooter’s likeness. Both stated most of these perpetrators thirst for the attention achieved by killing several people.

It’s difficult to dispute something like this when television news in its 24/7 news cycle clearly paints a picture of an individual who wants the attention.

The Aurora theater shooter, for example, told his psychiatrist that he feared he wouldn’t make his mark on the world in science. Despite being in the doctorate program, he dropped out of it and decided he’d make his mark through a mass shooting.

The shooter from Umpqua Community College in Oregon had a manifesto citing other mass shootings as inspirations. These events don’t exist in a tiny bubble that goes away once the media loses interest in covering it.

Journalists play an important and integral role in helping these shooters identify with other tortured individuals with similar tendencies. At the very least, taking up No Notoriety’s challenge could do more good than harm. And as Tom Teves said, “It couldn’t hurt to try.”

With attention taken away from the shooter, it would give viewers and readers a chance to hear more about the victims and the lives impacted by such a violent act.

The other half of the challenge is limiting and choosing carefully the likeness of the shooter. This would include images used while referring to the person.

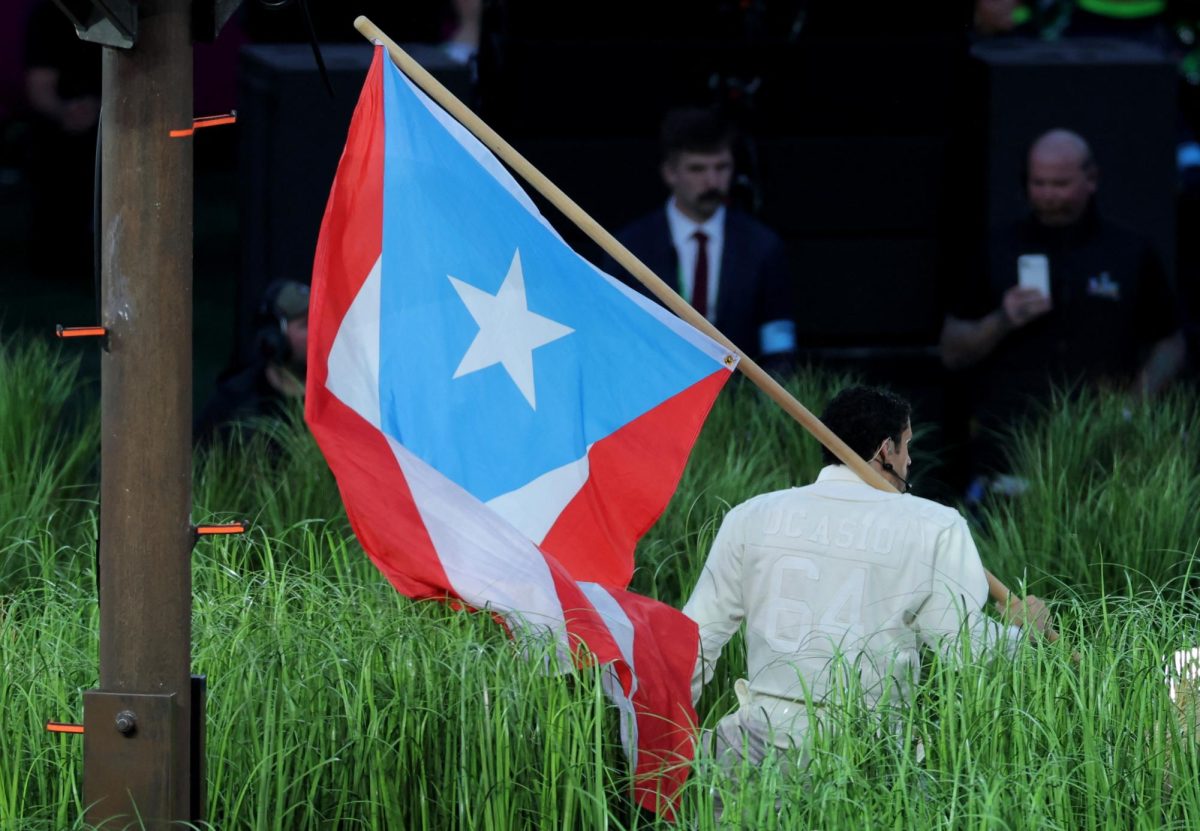

With the shooter at the South Carolina church, the picture that might instantly come to mind is a person wearing hunting pants and combat boots and dauntingly holding a handgun.

Or maybe it’s the photo of him proudly burning the American flag. Or the one where he’s stooped and holding up the Confederate flag.

Showing images like these can last in people’s minds long after the initial event. And while most people might associate those images with mental instability, some would consider them to be a display of strength and perhaps something to be admired.

People magazine’s editor Jess Cagle wrote in the Oct. 26 editor’s letter that his publication “will be careful to avoid giving individuals who commit or attempt these crimes more notoriety.”

After speaking with Tom Teves, CNN anchor Anderson Cooper made it policy on his show to reduce likenesses and name recognition.

News coverage of a mass shooting should not strive to play at viewers’ or readers’ curiosity in the macabre. It should strive to inform and, in cases of death, paint a whole picture, not just one section of it.

No more notoriety for those who do it through destruction and death.