Spellbound by the history of Salem, Massachusetts, four SE Campus instructors set off on an enchanted quest to explore the magical town that left them more bewitched by its story than ever before.

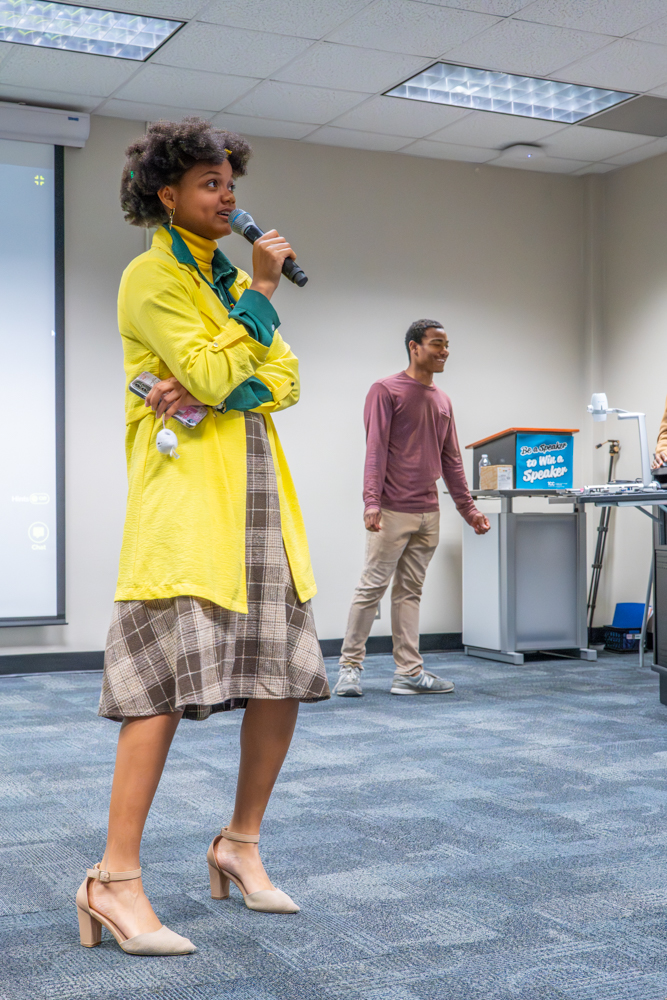

Yvonne Jocks, Leigh Anne Bramlette, Madison Durapau and Stephanie Hawkins sat in a circle when debating the different theories of the Salem Witch Trials in the late 17th century. Back and forth their conversation went, each possessing a unique expertise on the topic.

“I actually am a witch, a practicing Wiccan,” Jocks said.

She met the other instructors in 2019 during a trip to York, England. Prior to the pandemic, a program called Faculty Abroad funded their visit. This was when Jocks captivated the other instructors on the topic of witch hunts. “I kept trying to figure out the reasoning behind all of it,” Durapau said defeatedly. “It’s something that does not make sense.”

Durapau is mesmerized by all things spooky, but she discovered Salem’s dark story is too grueling for reason. She and Bramlette enjoyed digging into the psychological aspect of the history, but Hawkins stepped in as they became more exasperated in their discussion.

“What you’re doing is using logic,” Hawkins said.

Hawkins was the historian of the group. Each time a new part of the story was brought up, she would interject conversation with historical documents supporting what the other instructors would say.

But, as Hawkins noted, there was no logic to the witch hunts.

The four women discussed the fact that the craze began after the printing press was invented, and King James Bible was published, allowing people to read the text for the first time.

“All of a sudden, the church is now having to fight these people interpreting the Bible on their own rather than [being] told how to,” Durapau said.

Protestants allowed for followers to read the Bible while the Catholics didn’t. The rivalry between the two had already fueled conflict, but this established a religious war.

“The second best-selling book after the Bible was a witch-hunting manual,” Jocks said.

“Daemonologie”, written by King James prior to taking the throne, actualized witchcraft and claimed it to be evil. The book manifested a fear of what couldn’t be understood and became a term used to accuse people who were different.

“Before the great witch hunts, it was relatively safe to be a witch throughout Europe,” Jocks said.

The rise of capitalism in England followed shortly after, changing women’s role in society. Instead of working outside of the home, women were expected to have and raise multiple children for the new world.

“[Women] healers were vital to their communities,” Durapau said. “But that was not the case for the Salem Witch Trials.”

During a cold February in 1692, almost 40 years after the worst period of witch hunts carried out in England, the Salem Witch Trials began.

Samuel Paris, Salem’s minister, called upon a doctor when his daughter and niece began acting abnormally. It was reported they would stare off absent-mindedly or go into aggressive fits and make loud animal-like noises.

“When [the doctor] could not come up with a diagnosis, there was no answer other than witchcraft,” Hawkins said.

Tituba, an indigenous Native enslaved to the minister, was accused of using Bahamian folk-magic on the young girls and blamed for their outlandish behavior. Hawkins said this claim has since been disputed because descriptions of the magic used were English folk-magic, not Bahamian.

The young girls never claimed to be bewitched until the adults began asking them who had bewitched them, according to the instructors’ research.

“They were not the adults in the room,” Jocks said.

A copy of Cotton Mather’s book “Wonders of the Invisible World” was found in Paris’ home. This book tells a story of a family who had been bewitched in gruesome detail.

“Cotton Mather’s sources of witchcraft sound like something out of ‘The Ring,’” Hawkins said. “Jaws snapping, bones dislocating, it’s so detailed.”

The women said they believe during the long winter in Salem, Tituba read this story to the young girls, and it’s what influenced them to act out. Being a child in Puritan society meant they must listen and obey, and the instructors believed this was a way for them to get attention.

Either way, this event launched an accusation frenzy. Many people followed suit claiming others in the community had bewitched them, and after a year of Salem’s witch hunt 19 people were sentenced to death.

“None of the people who were executed in Salem were witches,” Jocks said.

Bridget Bishop, the first women executed, stood out from the rest of the community in Salem. She wore colorful clothing and owned a tavern, both of which were frowned upon.

“Marginalized people, the outcasts, they stood out and were executed,” Hawkins said. “When I think about the witch trials, I still see aspects of it, of people who have a hard time around those who are different.”

Their trip to Salem did not provide them with the answers they wanted, but rather it shed light onto the sinister past they knew of the town.

“It fascinates me, how they were othered in every way during their lives but now the town itself has made them, not a caricature, but a message of inclusion,” Bramlette said.

Salem has claimed witch and empowered the term. The instructors agreed the trip allowed them to expand beyond the dark witch hunt story and speak upon the town’s underlining message to be different.

“Salem has become this mecca for modern-day witches and Wiccans,” Jocks said. “The people who died were not witches, but they’re still ours.”

The four spoke for hours about the trials in Salem, down rabbit holes they went describing all their different theories but always circling back to the main point.

“Embrace being different, it’s great to be different,” Hawkins said. “You don’t need to fit in. You don’t need to conform.”