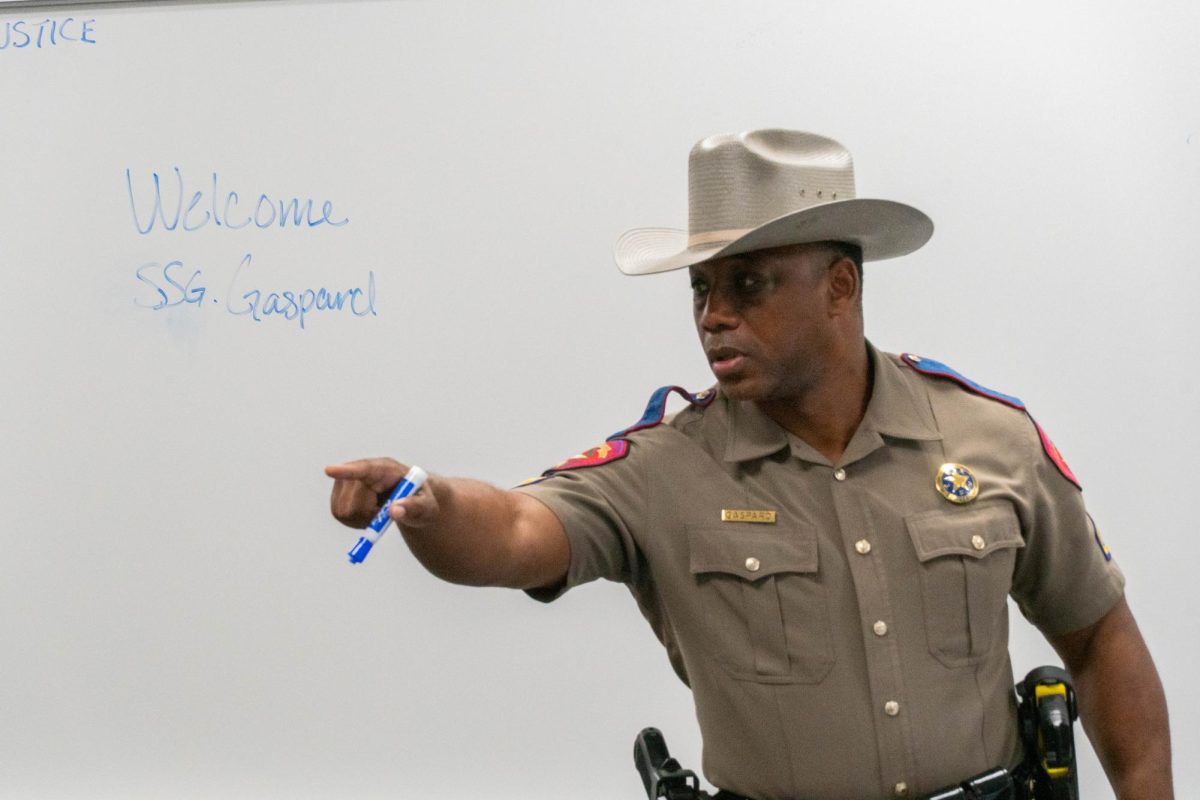

Photo by Casey Holder/The Collegian

By Ashley Bradley/ne news editor

Before SE student Eric Peterson knew about the world, before he knew about the “birds and the bees,” before he knew how to ride a bike, before he knew how to spell his own name, he knew he was adopted.

He would later find out that his name could have been Alma Gentry.

“My parents told me I was adopted before I even understood what it meant,” Peterson said. “Every April, we celebrate the day my adoption was finalized.”

Peterson also has an adoptive sister named Lauren. His adoptive father, Mike Peterson, made cartoon stories about their adoptions so they knew where they came from.

“We would show it to them before they went to sleep,” said his adoptive mother, Ann Peterson. “I thought it was the honest thing to do. They had loving mothers that wanted to give them to a family with a mother and a father.”

Because Peterson knew at a young age his parents weren’t blood-related, he began to imagine meeting his blood mother. When he would get in arguments with his adoptive parents, he would threaten to go live with his “real” parents.

“It was hurtful, but he was just trying to find out who he was,” Ann Peterson said. “He didn’t talk a lot about [his birth mother] growing up, but I knew he wanted to meet her.”

Because of adoption laws, Peterson had to wait until he was 21 years old to find his birth mother. Within a week of his 21st birthday, he contacted the adoption agency, Latter-Day Saints Family Services.

“I found out later that both of us had called the agency around the same time. Like a week apart,” Peterson said.

• • •

When Peterson’s mother, Kerri Rochelle, was 16 years old and living in Oklahoma, she got pregnant. She didn’t plan on telling her mother right away. She instead went to a friend’s mom for advice. When she came home later that day, her mother was sitting at the dining room table. The news had already traveled. She knew Rochelle was pregnant.

“She told me to come and sit down,” Rochelle said. “She never asked me what I wanted to do. She just said, ‘I know you’re pregnant, and this is what we are going to do.’ I never had a say.”

Her mother had strong religious beliefs, and she forced Rochelle to give the baby up for adoption.

Both her mother and their priest decided she would put the baby up for adoption through the Mormon church.

She then moved to Houston to live with a family who housed her during her pregnancy. After this time, she decided to no longer be Mormon.

“I was terrified because I was 16,” she said. “I was housed with a family that I didn’t know. I couldn’t participate or do anything with the youth group. I had to go to the adult services. I was stripped of all of my rights. I was dis-fellowshipped. It was very emotionally cruel.”

Peterson was born on Oct. 3, 1987, and Rochelle put the name Alma Gentry on his birth certificate.

Every year, she would do something special for the day, even though she didn’t have her son to share the celebration with.

“Every single year on Oct. 3, I would make or buy a cake and have a party for him,” she said. “Just me and the cake.”

She would then spend the rest of the month in a daze, wishing she had her son in her life.

“October was always the worst month of the year because I would go into withdrawal and get very depressed,” she said. “When I got older, I would drink for the entire month. Now that I’ve met him, that has all gone away.”

• • •

Three weeks after the two originally contacted the agency, they were given the other’s name and a phone number. Peterson was at work when he received the news and asked the agency to tell Rochelle to call him at 6 p.m. after he got off work.

Meanwhile, Rochelle was sitting in front of a computer in Indiana, where she was visiting her friend. Nervous about talking to her son for the first time, she decided to search him online.

“I went on MySpace and searched his name,” Rochelle said. “There were only two. I knew it was him. I was so glad he wasn’t Mormon.”

Though mothers don’t usually want their son’s status to discuss drugs, Rochelle was relieved.

“She got really excited that my status was ‘Staying high til I die,’ instead of saying I was going on a mission or something,” Peterson said.

Peterson and his birth mom talked for hours that night.

“I was so excited that I recorded our first conversation,” he said. “The most exciting thing for me was that I found out she wasn’t Mormon.”

The first time Peterson met his birth mom was at a Super 8 motel in Katy, Texas, just outside of Houston.

“She’s really cool,” he said. “She’s someone I would hang out and chill with.”

While getting to know his birth mother, he learned they shared the same taste in music and movies and that he had a half-sister named Bree.

“I had never told her that I had had this other son because I didn’t want to confuse her,” Rochelle said. “I told her the night before we went to meet him in Houston. She was so happy she busted out crying. Because we had just watched the movie Juno, in her 9-year-old mind, she understood why I didn’t tell her. She just kept saying, ‘This is just like Juno!’”

• • •

Because he wanted to get closer to his mother and half-sister, Peterson and Rochelle decided he would move to Fayetteville, Ark., and they would live together.

Originally, Peterson was going to wait until his apartment lease was up, but because he got fed up with his roommate, he broke the lease and said his goodbyes to Arlington, hoping never to return.

“I just wanted to leave,” he said. “I wanted to live with her.”

He lived in Arkansas for only one month.

Because Peterson couldn’t find a job, the two didn’t know each other well enough and the entire situation was stressful, Peterson moved back to Arlington.

“I didn’t want him to talk to his adoptive parents while he was here because I was trying to find out if I was his mother or his friend,” Rochelle said. “Because we are so close in age, it was hard to find a balance.”

Still in Arkansas, Peterson and Rochelle began to fight because they both thought creating the relationship would be easier.

“We ruined something great because we jumped into it too fast,” Peterson said. “That’s the lesson here.”

The two still stay in contact. They text regularly, and Peterson still talks to his half-sister.

“The first night he came to Arkansas, I came in from work and just sat in the doorway watching them interact. It touched me to see my two kids together, getting along so well. It was like they always knew each other,” Rochelle said.

The void that was missing in her life had now been filled. From the minute she gave Peterson away in the hospital room, she knew she would see him again.

• • •

They now keep a blog on MySpace named Alma Gentry. In the blog, Rochelle discusses her plans to write a book of the events.

In one entry, Rochelle shares e-mails from people who have become regular readers of the page. In the text, people reach out for help and advice on how to reunite with their adopted children and tell the stories of their personal reunions.

“Get ready to have the emotional roller coaster ride of your life,” said one of the e-mails.

In a later entry, Rochelle transcribed the journal entries she wrote while in the hospital for the delivery. She had three days with Peterson and cherished every moment because she knew exactly when the last one was going to come.

“Alma’s gone now. I spent every moment possible with him on Tuesday because I knew Wednesday would come quickly, and it did. I woke up this morning in pain, both physically and emotionally,” she wrote in her journal Oct. 8, 1987. “I live for the day I have my own baby, with a man who will support and love me and help me raise my child.

“I don’t know if I could ever have a baby as beautiful as Alma. But as soon as I’m financially ready and able, I’m going to have my own family and my own Alma.”

After years of waiting, Rochelle did meet her son. Though the relationship hasn’t come as easy as they hoped, they both love each other.

People dream of perfect relationships with others, including those who have long-lost parents, but most of the time that fairy tale doesn’t come true, Peterson said.

“Sometimes I think I should text her, but I just don’t,” Peterson said. “It’s like with my parents here. When they call sometimes, I don’t feel like talking to them on the phone for an hour, so I just don’t answer.”