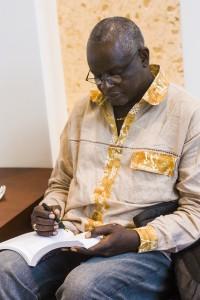

By Karen Gavis/editor-in-chief

As he stood in an underground dungeon filled with stagnant water, the tall, thin, French-speaking captive wondered if he would ever again see daylight.

It was 1998, and El Memeyi Murangwa was being tortured for writing a newspaper article about the genocide of the Tutsi people spilling from Rwanda into the Congo, his native country. His article asked those in power to halt the massacre of innocent people.

“For that reason, they [Congolese military] attacked my house. My house was destroyed, and I was jailed in a presidential camp underground,” he said. “The same Tutsi they killed in Rwanda, we have the same people in the Congolese, and they started killing us. They asked the population to kill us because the way we look.”

Murangwa’s ordeal took him from being a torture victim in Africa, to a refugee in New York, to a security guard in Fort Worth and finally, a TCC graduate.

He would see daylight again, but first, he had to make it through the ordeal.

Murangwa said the Congolese Tutsi organized to protect themselves, and many in the east of the country were being arrested and interrogated as rebels, and innocent people, including women and children, were jailed.

“Army, police and citizens were killing people. They killed a lot of people in August 1998,” he said. “They killed all members of the Tutsi who were in the army or government. I survived that killing.”

While being interrogated, Murangwa said he was beaten, his arm was broken and his back was burned by electrical wire. When it rained, water would seep and rise in his underground cell, and he was forced to eat, drink, stand and urinate all in the same water.

“That water was my food,” he said. “Sometimes, I would try to see if I could find something to eat in there.”

But that was before he heard the sound of a familiar voice.

One day, Murangwa said, an Army general came to the camp and ordered the prisoners brought up. When the guards opened the cell doors, those held in the cells beside Murangwa were dead.

“I was the only one who survived those conditions,” he said.

Though still alive, Murangwa said he had dwelt in darkness for so long that when he was brought above ground, he was unable to see. However, he recognized the general’s voice as that of a friend from elementary school.

Hearing his friend’s voice made Murangwa smile, and the general recognized the gap between Murangwa’s teeth.

“He recognized me that night. Before that, it was hard for me,” he said. “I was in very, very bad shape.”

Murangwa said guards took him back to his cell, but the general kept the key.

“They could not open it [the cell] anymore to torture me,” he said.

Afterward, Murangwa said the general’s wife sent buttered bread to his cell. Within a few weeks, he was freed.

“I was starving,” he said. “I was almost naked.”

Murangwa was covered in lice, he said, and an officer took him to a barber, bought him clothing and instructed him to drink but not eat anything for four or five days or he would die. He was experiencing starvation, and his body needed to readjust to food.

After that, Murangwa said he was placed under international protection. The United States had provided 1,500 visas for Congolese refugees.

“Of my people, I was the leader of the community. I was saved in 1999 by the U.S. State Department who decided to give protection to Congolese Tutsis,” he said. “We were escorted by the Red Cross. They brought buses to get us to the airport. Anything could happen at that moment.”

Murangwa was later flown to America where he stayed four days in New York. Without enough time to properly say goodbye to their fellow countrymen, groups of refugees were then dispatched to different cities.

In March 2000, Fort Worth became his hometown, Murangwa said.

He worked as a security guard on TR Campus, where he said he met TR president Tahita Fulkerson.

“During my patrol, I escorted the president to her car,” he said.

Murangwa said Fulkerson thanked him and told him to let her know if she could do anything for him. Later, he visited Fulkerson’s office and shared his story.

“She took me from her office to the registrar office. From the registrar office, I was sent to the testing center, and I passed the test and was able to register for classes,” he said.

Murangwa will graduate from TCC May 10.

“I feel great. I’m excited about it,” he said.

Fulkerson said Murangwa is the type of student TCC is designed to serve. She described him as a soft-spoken, gentle, unassuming, modest man with a wonderful smile.

“I will be happy to applaud him as he walks across the stage,” she said. “He is an amazing man.”

Murangwa said the English language has been his biggest challenge, especially during job interviews. But he plans to major in communications and wants to work as a public relations officer helping people to better understand American culture.

TR English associate professor Mary French said Murangwa was a delightful student with much to add who was interested in Egypt and ancient literature.

“There was a gentleness to him, a positive quality,” she said. “I very much enjoyed him as a student.”

Murangwa said he thinks graduating from TCC will be a good example for his children and other Tutsis in the area who still work menial jobs after more than 10 years.

“We stick together as a community,” he said. “We share a common past.”

Murangwa said people have misconceptions about Africa and think the continent is poor. However, it produces gold, diamonds, coffee and other items of wealth.

“The country is not poor. It is the way they do business is not right,” he said.

Part of the problem, Murangwa said, is that government workers are paid under the table, and soldiers are provided guns but no wages. It would be better to make sure soldiers were paid and hospitals had mattresses, he said.

“If you want a birth certificate, if you under the table give $20, you get it,” he said. “If not, you don’t get anything. That is the problem. Can you imagine living in a country like that?”

Murangwa described soldiers in ragged clothing without money but wielding weapons coming upon a woman working in a field demanding that she lay down.

“She wants to be alive,” he said. “When one do it, the other ones come. In America, it is different. You don’t pay the government workers [under the table].”

The general, Murangwa’s elementary school friend, is now imprisoned, but Murangwa is in touch with his family, he said.

As for Murangwa, he continues to write and hope for changes in his homeland.

“I’m still writing,” he said.