Art is about making emotion visible — and while works of art are fulfilling to look at and to make, they can serve a practical purpose with just about anyone’s mental health.

The last year and a half has been a lot to handle. Science backs this up — in the first year of COVID-19, symptoms of anxiety and depression jumped significantly in adults, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As a result, countless people worldwide have turned to professional help to cope with the trauma spurred by isolation and a new way of living. The use of therapy is up, which is a very good thing.

But sometimes, gathering thoughts is hard.

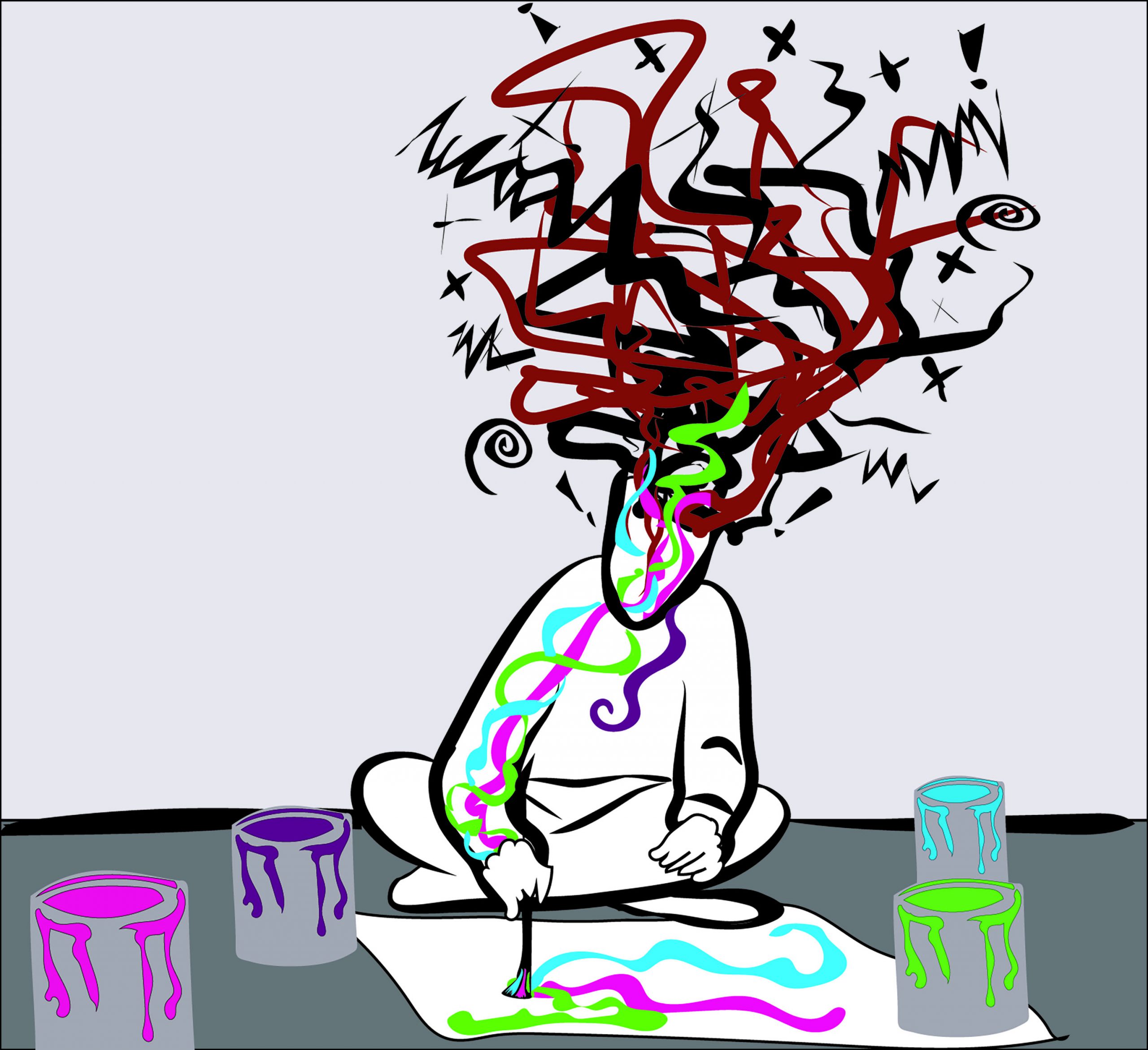

How many times in the last year has a patient sat across from their therapist, teetering on the edge of a breakthrough, and felt a complete loss of words? Trained professionals are experts at talking patients through these moments, but sometimes the words just won’t come no matter what. The ideas are there. There are thoughts buzzing around the back of the mind, filling every nerve with meaning, but the patient is unable to make sense of them.

Therapy is all about working through issues and trauma by collecting thoughts and making them verbal. When these thoughts are jumbled and confusing, taking paint to canvas and pen to paper can give them a literal shape.

Art therapy draws on the subconscious. It brings ideas from the back of the mind and places them on paper. It gives insight into what the artist is feeling and how they view those feelings in ways that words may not be able to express.

On a purely physical level, art therapy gives the patient something to do with their hands. Not a distraction, but a focused motion to stir ideas. The calm swipe of a brushstroke. The smooth glide of a pen. Patients feeling a loss of control can find comfort in these things.

Oftentimes, art therapy is more about the act of art-making than it is about the final product itself.

This is why patients who might not consider themselves creative, or who might not have experience with visual art, can still find meaning in its process. Colors and shapes stimulate thought. Knowing exactly how colors and shapes unfold and take form can give insight into how thoughts come to be.

This isn’t to say that valuable information can’t be pulled from a piece of artwork made in a therapy setting. In fact, the opposite is true — the final product can be a stunning embodiment of the issues consuming the artist at the time. Even works of art made without technical proficiency can deliver an arresting impact.

While painting is probably the most common medium used in art therapy, many other methods are used to help patients heal. A popular alternative is the use of collage-making with magazine cutouts — a method that can be especially beneficial to people intimidated by the endless possibilities of paints. Like the calming effects of paint, cutting and pasting images can provide physical, emotional and spiritual insight. A collage is all about comparing and contrasting images, which can help a person dig deeper into themselves and how they perceive the world.

When an artist views the art they make when thinking about a specific experience, they learn more about that experience.

There is precedent for using art as therapy during times of national crisis. The practice has its roots in the U.K. and the U.S. following the second world war when mental health facilities began treating the post-traumatic stress disorder of returning soldiers by allowing the soldiers to paint.

The process is just as beneficial today. While there are many professional programs that use art to supplement traditional interview therapy, the creation of art in any context is therapeutic.