OLLA MOKHTAR

campus editor

olla.mokhtar@my.tccd.edu

During one of his shifts, TR student Marc Núñez-Díaz said his supervisor was going around giving nicknames to his favorite employees.

When it came to him though, the supervisor gave him the name “Fruity Pebble.”

Núñez-Díaz is all too familiar with microaggressive comments as a queer and bilingual Mexican American man, this was just one of many he has gotten.

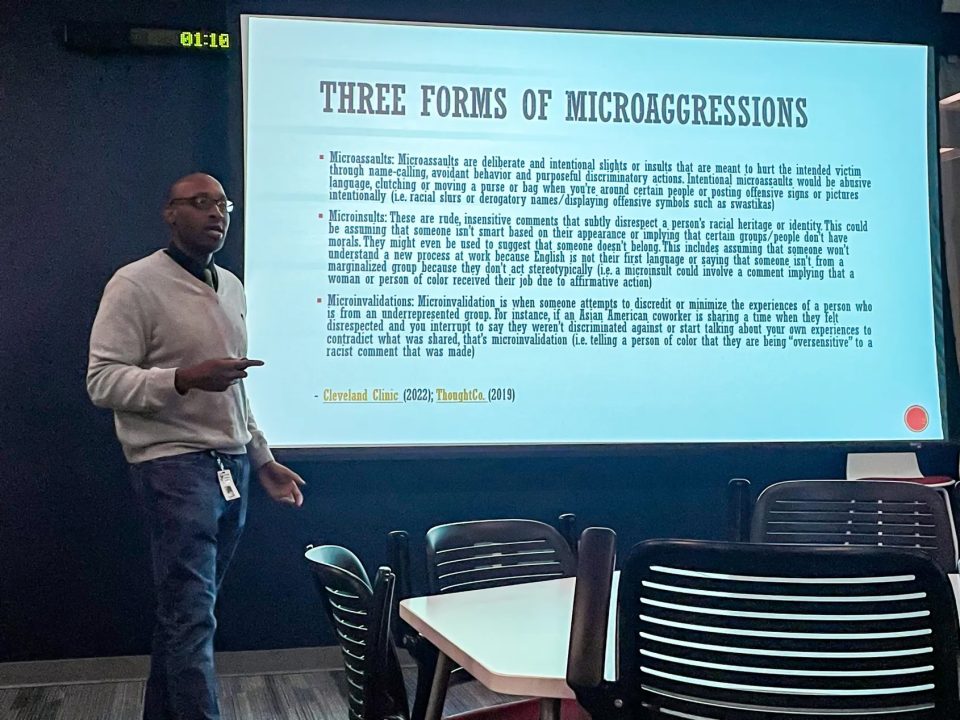

TR counselor Osaro Airen, Ph.D., explored how the comments Núñez-Díaz impacted people of marginalized communities during a presentation titled Microaggression in Mental Health.

Though the original definition of microaggression was given by Dr. Chester Pierce, Derald Wing Sue, Ph.D., refined the term to what it is today. Microaggressions are everyday verbal, nonverbal and environmental slights, snubs, or insults, whether intentional or unintentional which communicate hostile, derogatory or negative messages to the target person.

Airen said it can happen to people of color, LGBTQ+ groups or really, any marginalized group.

What Núñez-Díaz was experiencing was one of the three types of microaggressions, a microinsult. These are rude, insensitive comments that subtly disrespect a person’s racial heritage of identity, Airen said.

After the comment, Núñez-Díaz felt weird because his supervisor was a straight man joking about him being feminine and queer.

“I felt pretty “othered” when he said that,” Núñez-Díaz said. “I wish people considered that joking about someone’s identity, whether it be race, religion, gender, sexuality, etc., is harmful, so late in this age, and in line with something that a white supremacist would say.

He didn’t know how to react when his supervisor said that, but one thing’s for sure, he wishes he stood up for himself.

“I could’ve retorted with ‘And my nickname for you is ‘Homophobe’. Don’t do that.’” he said.

A takeaway from Airen’s presentation is the comparison between microaggressions and death by a thousand papercuts, Núñez-Díaz said.

“Each offense does not seem to be harmful, when in actuality they are,” he said. “Your feelings are valid and it’s important to stop someone from continuing their harmful patterns of behavior, these are things that I wish my younger self knew.”

“I could’ve retorted with ‘And my nickname for you is ‘Homophobe’. Don’t do that.’” he said.

As someone who focused his dissertation on multicultural affairs, he has worked in many diverse communities. Airen said receiving microaggressive comments can affect one’s physical health because of the stress it imposes on their psyche. Because the body is connected it can affect their mental health as well.

In this event, Airen said it was paramount to speak up, respectively and letting them know that it isn’t right. A lot of times, when people receive these types of comments they retort to laughing nervously because people don’t want to be “othered.”

“But the question is, are those the people that you actually want to associate with in general?” Airen said.

During the presentation, he emphasized that people should stand up for themselves and not be apologetic by saying something. Even if people say taking it to an authority figure is too much, or it isn’t a big deal, they should respond with “It was a big deal to me.”

“If it affects them, and it’s not fair to them, then that’s all that matters,” Airen said

TR student Jason Wilson said the reason he came to the event was to profess his ignorance and learn to better communicate with the younger generation.

Several scenarios were given to the audience to promote discussion. One of them being how the Vietnamese American CEO of a hospital was presumed to be an intern by the chief nurse during a tour for donors. The chief nurse proceeded to interrupt the CEO and demand she do something else.

“There was a lot of assumption,” he said. “A person would not only assume, but then they would intentionally involve themselves in a situation of, this person can’t be giving this tour to this group, because they’re this ethnicity. So, for me, personally, taking a step back trying to be more observant, trying to listen and then respond and not necessarily react to a situation.”

As a former military serviceman, he noticed that a lot of conversations regarding microaggressions wouldn’t be addressed. This included an instance where he was doing a funeral service with two other African American military servicemen.

When the family of the deceased went to talk to the three of them, they only addressed Wilson assumingly because he was the only one that was white, Wilson said. This happened even though he was the lowest ranked out of the three.

Having grown up in Louisiana he also noticed that the mindset of not talking about these instances was rather pervasive. It is only when one emerges from their environment and being exposed to other people that people learn what’s acceptable, he said.

Having conversations and divorcing from the idea of following in the older generations’ ideas about microaggressive behavior is one thing he’s learned to do once he became an army veteran.

“It’s like relearning how to communicate,” he said.

Connecting with others and sharing experience is what Airen hopes the students will take away from the presentation because shared experiences are very powerful. They make people who don’t even know each other connect with what they don’t know or what they need to learn.