Logan Evans

managing editor

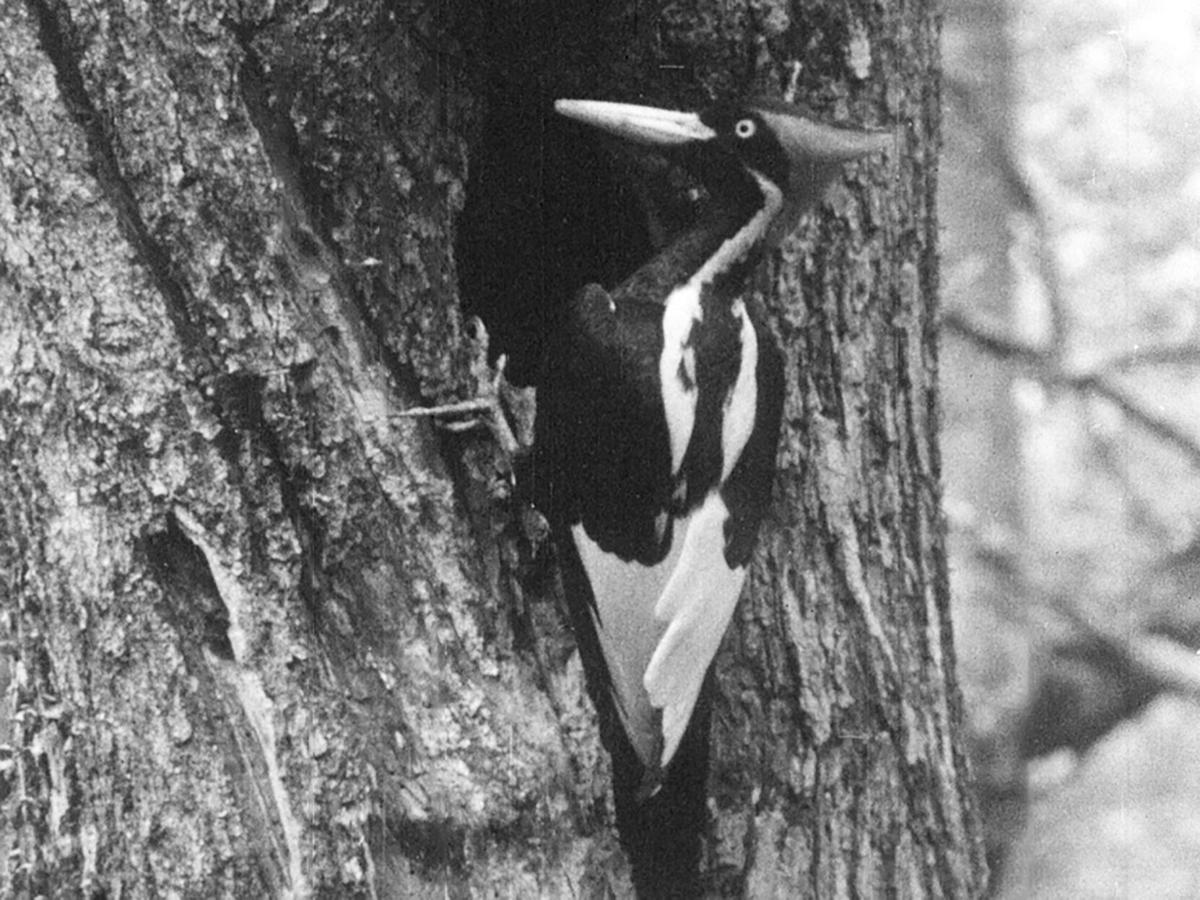

The ivory-billed woodpecker was one of the largest woodpeckers in the world. At 20 inches long, it boasted a 30-inch wingspan and a stark display of black-and-white feathers. The males sported a bloody shock of red on the backs of their heads.

It was nicknamed the “Lord God” bird for what birdwatchers might shout after seeing one. But it will never be seen again, according to a recent proposal by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The proposal seeks to remove 23 plants and animals from the endangered species list due to extinction — the largest proposed batch in history.

While it’s easy to hear news like this and feel hopeless, it’s important to think about species that are endangered, how they become that way and the threat of more magnificent creatures living among us being snuffed out forever.

Oftentimes, extinction impacts not only the species being depleted but other organisms living within their ecosystems. Among the species listed in the recent proposal is a group of freshwater mussels, many of which became extinct after the U.S. built dams in their habitats along the Eastern side of the country. This led to a shrinking habitat, which was further invaded by pollution.

There were once three hundred species of mussels in the United States. They supplied food to Native Americans and people harvested them for pearls and for mother-of-pearl to make buttons. Now, hardly anyone eats freshwater mussels and buttons are mostly made of plastic.

Freshwater mussels filter water and work to stabilize riverbanks. Because of their extinction, others within their ecosystem will surely suffer.

As for the ivory-billed, the elusive bird once populated stretches of woodland in the South. When timber companies began churning through forests in the early 20th century, the bird quickly disappeared.

In fact, the USFWS cites the last confirmed sighting to have been in 1944. Reports in 2005 of sightings in eastern Arkansas ignited a frenzy of birders and biologists scouting the area. The most credible proof of the bird found at this time was a pixelated video taken from a kayak of what might have been one fluttering in the distance.

Now, all that remains of the “Lord God” bird is an archive of more than 60 lifeless specimens at Harvard collected between 1869 and 1914. Their stilted bodies and zig-zag feathers give us a small idea of what they might have looked like alive and in flight.

So how can we prevent more endangered species from reaching the same fate? A big part of the answer is proper funding.

The Endangered Species Act, passed in 1973, has prevented a reported 99% of the species on the endangered list from becoming extinct. This is proof that funding and legislation geared towards nature conservation works.

The ESA has not been fully funded for decades. As of 2019, hundreds of endangered species were receiving less than $1,000 a year for their recovery. Some receive none at all.

With a fully-funded ESA, we can conserve nature better. Until then, more animals will be doomed as the Lord God was — lost to the wilderness of the past.