Logan Evans

managing editor

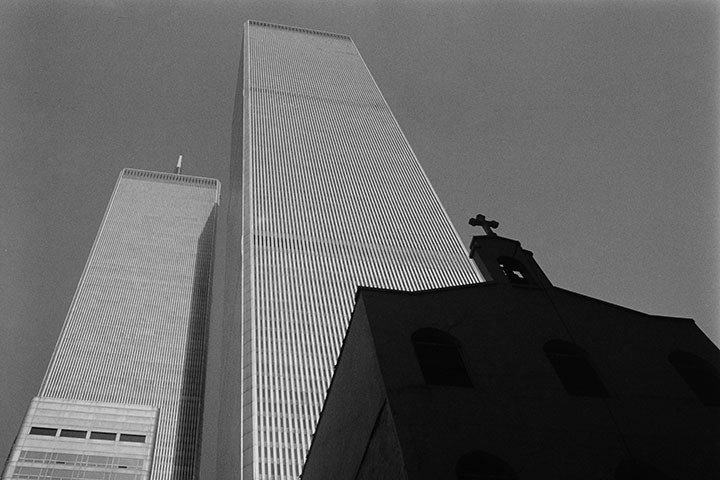

Settled in the heartland of North Texas, Tarrant County sits some 1,600 miles from New York City — a world of difference in terms of culture, landscape and attitude. But on the morning of Sep. 11, 2001, that distance was folded in on itself as the country came together to grieve.

SE associate professor of history Kristan Foust was a student attending NE Campus when news of the attack broke. Classes were immediately canceled for the rest of the day. Foust and her roommate began packing their bags, planning to drive to a family farm in West Texas, where they’d be safe in the event of additional attacks.

“We were all so scared,” she said.

NE instructor of history Samantha Elkins was only in sixth grade. She remembers teachers whispering to one another outside her classroom at J.B. Little Elementary in Arlington. There was a tension choking the air, she said. Something was happening, but her classmates didn’t know what. Then came rumblings that a group of students down the hall was getting to watch TV during music class.

By the time Elkins went to music class, the TV was turned off.

“When the first plane hit, everyone kind of assumed it was an accident,” she said. “When it became apparent it wasn’t, the school didn’t want to scare any of the students who might have family traveling on planes.”

Two decades later, Elkins looks back at that day as a turning point, both historically and personally. New fears began sprouting up in the U.S. over national security and terrorism, things that everyday citizens were hardly thinking of before. Fear was rampant.

“In many ways, 9/11 was the end of my childhood,” she said.

But above all else, Elkins looks back and admires the people who did good when times were the hardest.

“People came together, they gave,” she said. “The first responders were incredible for what they did at ground zero.”

TCC coordinator of fire services Bill Pearson was a Fort Worth firefighter in 2001, but on the day of the attacks, he was off-duty meeting a friend for coffee. Watching NYC firefighters disappear into clouds of smoke, he thought to himself, “There’s a good chance some of those guys aren’t going to go home.”

Twenty years later, Pearson and his department use the memory of that day and the 343 firefighters who were killed in action to teach their students — many of whom weren’t yet born — of the danger inherent to their career path.

“With the job, there’s risk,” he said. “There’s going to be some tough days. It’s what those guys experienced.”

All told, around 3,000 people were killed by the attacks in 2001. In addition, over 6,000 were injured and reports of hate crimes against Muslims spiked.

During this time, NE intercultural network coordinator Marjeanna Burge decided to visit a mosque with a non profit she was working for. Muslims in the area had been receiving death threats, and Burge’s organization wanted to show solidarity.

“I’ll never forget the smiles, the hugs,” she said.

Burge said she recognizes a pattern in how we sometimes respond to tragedy, comparing the stigma that followed Muslims after 9/11 to the reported rise in anti-Asian hate crimes in the wake of COVID-19. She believes there are lessons to be learned.

“There’s a bigger picture somewhere than just us,” she said. “These experiences we go through are an opportunity for us to learn and do better.”

Two decades later, Americans remember the lives lost, sacrifices made and the compassion that can bridge any distance — physical, spiritual, or otherwise.