(Ariel)

NINA BANKS

campus editor

nina.banks@my.tccd.edu

Since the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, the education of racial issues has become a hot button issue in politics.

The matter has become politicized with officials such as Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis defended the choice to reject AP African American studies from Florida curriculum citing that it is “indoctrination.”

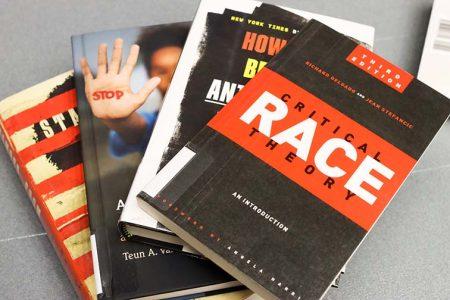

Among the topics that conservative politicians have attempted or successfully restricted from school curriculum is critical race theory. According to Merriam-Webster, critical race theory “[examines] the relationship between race and the laws and legal institutions of a country and especially the United States.” SE history instructor Eric Salas believed people fear what they don’t understand.

“The way we alleviate fear is by increasing knowledge,” Salas said. “If we increase our knowledge as to what critical race theory is then we would probably be less apprehensive towards it.”

The censorship of books centering around race and LGBTQ+ issues has been enacted in several school districts in Texas. Though the bans are primarily in public and K-12 libraries, SE public services librarian Matt Butler felt college libraries may be next.

“It’s been felt more in the public libraries,” Butler said. “But I feel like it could possibly start coming for education and college libraries. But as of right now, it hasn’t really happened yet but I feel like it’s coming.”

For SE student Syrina Kimuyu, the lack of education surrounding Black history is not surprising.

“We didn’t speak about it,” Kimuyu said. “There were teachers who were teaching incorrect information.”

Opponents to using critical race theory in the classroom argue that it is discriminatory to white people. However, Kimuyu believed learning about it is necessary to learn.

“We don’t want to make the same mistakes that we have in the past that shouldn’t have even been made,” Kimuyu said. “I don’t care about the guilt, we need to learn about it.”

Teachers may face scrutiny over discussing current events without going over both sides of an issue, which may defer many from even discussing these topics at all. Salas understands the hesitance teachers may have to explore certain ideas.

“Yes they’re afraid,” Salas said. “High school educators work 40 plus hours a week, and everybody argues that public school teachers don’t get paid well. If that’s their gig and it gets threatened, then it isn’t even worth the hassle.”

Despite the often polarizing debates, Salas hopes that individuals can learn to understand one another.

“Because I understand something means I agree with something, that’s not true,” Salas said. “I can understand you and not agree with you. And I think in the classroom we should instruct students to think critically and that it’s OK to understand things and not agree with it.”