By Andrea Conley/reporter

Tall, dark, heavily tattooed and possessed of a dimpled, baby-faced smile, the 21-year-old blends into the scenery, so to speak. At TR Campus, he fits the same general description of hundreds, if not thousands, of students.

But Antonio, who asked that his last name be omitted from this story, could not be more different than the average first-year college student. He is a former gang member who was selling crack by the time he was 14 years old.

He lives in an entirely different world now, and he is eager to share how he went from the world of “street pharmacy” in Arkansas to the world of research papers, math labs and final exams here in North Texas.

By the time he was 8 years old, Antonio liked having a lot of money in his pockets.

“You know the chocolate candy they give little kids to sell for fundraisers? I used to sell it and keep all the money for myself,” he said. “Sometimes I would be carrying around $400 or more.”

By age 13, he was hanging out with gang members. And at age 14, an “O.G.” (original gangster) introduced him to crack.

“He stressed for me to never use the drug, but he taught me to cook it and sell it,” he said.

By his mid-teens, Antonio would be jailed time and time again for possession. But when he was not locked up, he attended school and made good grades in spite of his poor choices in friends and business activities.

“Sometimes I got expelled and sent to alternative schools,” he said. “But I would eventually earn the right to return to public school, so I finally graduated.”

Graduation, after all, had always been a priority. It was something he had often discussed into the wee hours with his 16-year-old sister, Dominique, who was also a good student and who had been his best friend. When Antonio was 14, she died in a house fire.

He decided he would graduate in memory of her because she had been so excited about her own plans and goals for an education.

“I wanted to make sure to graduate because she never got her chance to,” he said.

Antonio, whose grief and devastation would slowly drive him further into gang life, credits his stepfather for making sure he did not get into even worse trouble than he did.

“I came to Texas during summers and stayed with him. While I was with him, he kept me on the straight and narrow,” he said. “He married my mom before I was born, so he was the only father I had ever known.”

It was only when he returned to Arkansas after summer vacations that Antonio would resume his criminal activities.

“By the time I was 15, I had bought a gun — a .357,” he revealed.

He continued to get caught in possession of crack and was sent back and forth to jail. The turning point came when he was about 18.

“This time, while I was in there, I changed my whole mindset,” he said.

For starters, nobody, not even his mother would write or visit him. He had a lot of time to think. He usually refused to eat at all. Now slender and athletic, he recalled weighing more than 300 pounds when he was last incarcerated.

And Antonio was particularly struck by things like seeing his cellmates eating the food he had angrily tossed into the trash. When he was finally released just before he turned 19, he vowed to never go back to jail.

“I used to donate plasma three times a week. That was the only money I had after I spent my savings,” he said.

Antonio recalled having about $10,000 in cash hidden in a shoebox.

“I saved that money for years while I was younger selling crack. I finally used it — about $4,000 to buy a car after I got out, and I gave the rest to my mother and my granny.”

He would eventually grow tired of the paltry proceeds from donating plasma and began selling weed.

“But I never touched crack again,” he said.

Antonio’s beloved stepfather died of cancer in 2006. But not before he introduced Antonio to his biological father. In 2008, he reconnected with his biological father and learned of several half-siblings, including a sister his same age. They became close in a way that comforted him and reminded him of his sister who had died.

“It took about three or four months, but she convinced me to move here and enroll in school,” he said.

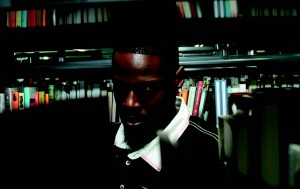

He now supports himself with the meager earnings he gets through work study. His co-workers in the library are quick to offer praise to the young man who describes his life now as a “rebirth.”

“He takes initiative. He offers to take on anything I need him to do,” said librarian Stephanie Wineman. “I’m happy to have him back for this school year.”

Another TR librarian, Andrea Neal, recalled what Antonio was like when she first met him.

“He was very quiet, very reserved,” she said. “Now, you can see him coming out of his shell. He is much more confident when he is helping students. And he is taking steps to learn more about his job.”

He is completing his core requirements for his associate degree, after which he plans to study kinesiology and possibly become a coach.

He now spends his free time studying and talking with several teenage cousins about the importance of steering clear of the life he feels fortunate to have escaped.

Antonio believes he has been successful in staying away from drugs and gangs for the past two years because he is far removed from the negative influences in his past. He said his experience has made him more careful in choosing friends.

“If I meet somebody who reminds me of a person I used to hang with, I make better decisions — to not socialize with them,” he said. “TCC has helped me out tremendously. Without them, I wouldn’t be where I am now.”