By Kirsten Mahon/tr news editor

Multi-tasking is one thing, and self-absorbency is another.

Students are doing both, and it’s not just students either. Even faculty members are victims of the techno-busy world, using speakerphones in their offices and texting on the go.

“I can call somebody, talk to them while I’m typing an email,” said Stephanie Blakely, TR coordinator of student success. “Is that really giving either task 100 percent of my attention?”

Blakely calls it splitting the brain. Doing five things at once means each of those things is getting only 20 percent of the attention.

“What does that mean for my work? I’m certainly not getting an A,” she said. “And you know we’ve come to this idea where we have to get stuff done, and deadlines are shorter. And so I have to call someone and email at the same time … I don’t have a choice.”

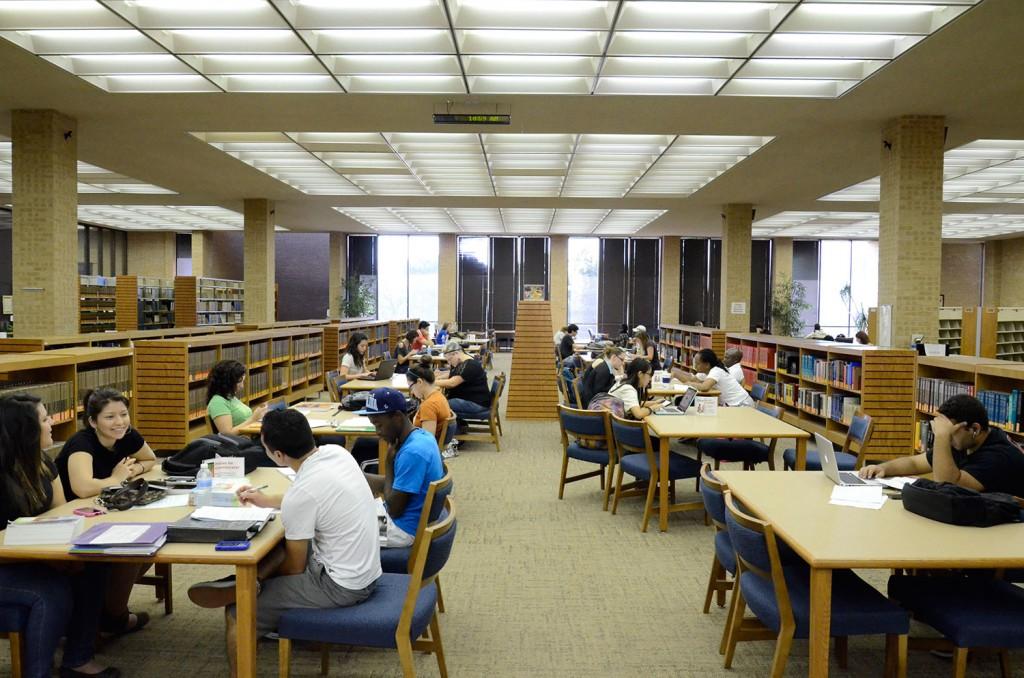

Students today are expected to do more than they were 10 and 20 years ago, Blakely said. Before they had cell phones and beepers, students were considered full-timers at just nine hours. Now that 12 hours is the minimum for a full-time student, most students who finish within four years often end up taking 14, 15 and 16 hours per semester. If they have jobs as well, they are constantly in between the two and home. If they have families, they are juggling all three with a cell phone on and glued to the inside of their palm because it is impossible to be in more than one place at a time.

Cheryl Law, TR speech instructor, said dependence on electronics affects everyone.

“When you talk about communication, you’re talking about face to face. It’s a transaction,” she said. “You take in what they’re saying, their behavior, the verbals and non-verbals. All of that matters. You can’t do that when you’re focused on something else. And when you’re multi-tasking, what is that telling the other person?”

Some people spend 20-40 hours in virtual communities now, rarely having to leave their homes at all, Law said. Yet they are just as connected to the screen as the busy-bee student with a to-do list longer than the student’s body.

Blakely wonders how often students have hurried from one class to another never looking up long enough to see someone they know pass them and say “hi.” The struggle to even notice each other is beginning to become the struggle to communicate in general, let alone in person, Law and Blakely agree.

“They write emails to their instructors as text messages,” Law said, referring to students. “They don’t use capital letters or punctuation. It’s just one big, long text.”

Technology has brought society many ways to communicate but rendered our communication to the bare minimum because of it, Law said.

“It is becoming difficult to communicate because you have to talk in their language now,” she said.

Blakely said people should worry because some students aren’t learning how to have a face-to-face conversation with authority or how to talk appropriately and treat each other respectfully.

“We have to adjust,” she said. “We’re getting to a boiling point where the pendulum is swinging back the other way.”

Blakely and Law agree that by living on screens, students are losing touch with their environments and can barely react to each other in passing. The path the younger generation is headed down will only create barriers instead of bridges.