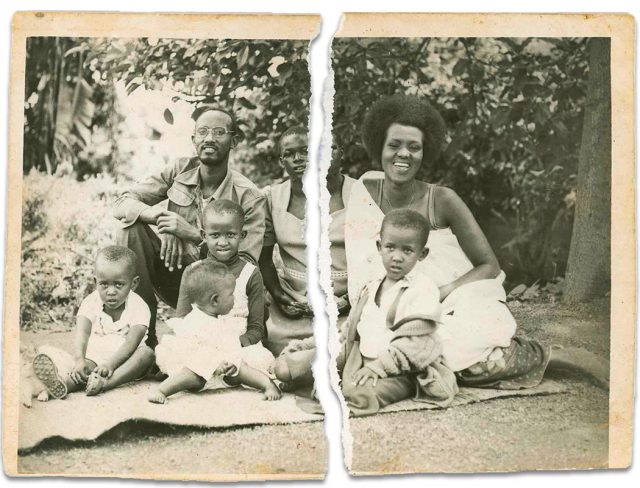

– Photo courtesy Blandine Uwambaye Ntagwabira

Rwandan genocide: 25 years later

By JW McNay/Editor-in-Chief

For most people, April may not hold much significance.

For NE student Blandine Uwambaye Ntagwabira, she understands the pain the month can bring. Blandine survived the Rwandan genocide, which started 25 years ago this month.

“You feel like ‘April is coming,’” she said.

The Rwandese and rest of the world recall each year the 100-day period beginning on April 7, 1994, when an estimated 500,000 to 1 million people were killed. The U.N. commemorated this date as an annual International Day of Reflection.

For survivors like Blandine, the 25th anniversary of the genocide relives the trauma of a time when the people of the country didn’t consider themselves Rwandese but rather belonged to one of three ethnic groups: Hutu, Tutsi or Twa.

In elementary school, Blandine, a Tutsi, recalls her teachers taking time to ask students “Who are you?” in reference to their ethnicity, which led her to ask her dad why it was necessary.

Blandine’s dad told her there wasn’t anything she could do to change it. That’s just their identity.

“But to me, it was no identity,” she said.

In 1994, Blandine was only 11 years old and didn’t fully understand the history and political factors that contributed to that mindset.

At that time, the Hutu people were the majority and controlled the government as well. The assassination of Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana, a Hutu, set in motion the events of the genocide. As it was believed the Tutsis were responsible, Hutus took revenge on Tutsis, who were targeted and systematically slaughtered.

At that time, the Hutu people were the majority and controlled the government as well. The assassination of Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana, a Hutu, set in motion the events of the genocide. As it was believed the Tutsis were responsible, Hutus took revenge on Tutsis, who were targeted and systematically slaughtered.

Being Tutsis, Blandine’s family abandoned their home in an effort to find safety. Her father told her to throw away the key to their house in the city of Butare, which confused her at the time because she didn’t know how they would be able to get back in later.

“My dad looked at me and said, ‘I don’t think we’re going to get a chance to go back,’” she recalled.

Along with her family, she took refuge in a Catholic church outside Butare in addition to 600 other people. The church previously had been a safe haven, and there was an expectation that militias wouldn’t attack the location.

However, the church didn’t offer the protection they expected. Her family was killed in front of her: Her father, shot near the heart; her brother, a grenade; and others, killed with machetes.

“I got a chance to survive,” she said. “It’s not because I wanted it, but it was God because I didn’t do anything to get a chance to survive, to be honest.”

After rounding them up, the killers used gunfire aiming above the crowd to cause them to drop to the ground. While vulnerable, the defenseless people were struck with various weapons.

Blandine’s left index finger was broken when she instinctively used her left hand to protect her head. She was a wearing a small necklace her dad gave to her for her birthday. The killers used a knife to take it from her and cut her neck.

She awoke among the bodies weak from blood loss, looking for where to go. Thinking about returning to her house, she found out it was already destroyed.

She awoke among the bodies weak from blood loss, looking for where to go. Thinking about returning to her house, she found out it was already destroyed.

Blandine wasn’t confident she would make it to a refuge because checkpoints were set up all throughout the cities. She spent some early nights in a nearby forest and waited while the sounds of alarms and people’s death screams could be heard in the distance.

Blandine was the only one of eight siblings who survived. However, surviving meant that people were still searching for her as well as other Tutsis.

It was unsure whether Hutus would immediately turn her in or kill her, and any Hutus who opposed the genocide were just as likely to be killed, especially if they were found sheltering a Tutsi.

At such a young age, her only hope was to find family ties. The first family she reached included a close friend of her mother.

“They were surprised to see me because nobody was expecting anyone to survive,” she said.

This, like many subsequent visits, yielded a short stay — one day, in this case. The danger was too much for the family, but they helped connect her with an old friend of her dad who wanted to help.

The family was ready to help, but much like her previous temporary home, they were worried about the consequences for housing a Tutsi.

“They were not happy because they knew if [others] found me, they’re going to die,” she said.

“They were not happy because they knew if [others] found me, they’re going to die,” she said.

She stayed three days before being moved, but her next destination required a four-hour walk in the morning hours. However, a man living at the residence refused to help Tutsis. He didn’t see her as an innocent little girl but said she had “poison like a snake.”

And just like that, she was on the run again.

Having to put thoughts of being tortured and killed aside, she ended up with a new family who also had children from her elementary school.

“When I found there were young kids in the house, I was like, ‘This is the end. I’m going to die because there is no way the kids can keep a secret. They’re going to tell the people I’m here, and they know me,’ but they didn’t say anything,” she said.

But the search for Tutsis still wasn’t over, and she could not stay there after a visitor to the house questioned who she was.

Her options continued to be limited. At one point, it was suggested she escape and take refuge in the nearby Democratic Republic of the Congo. However, some Hutus also had gone to the Congo, so she was unsure if she could really be safe there.

Through more connections, Blandine ended up with a family who housed her for months. And as the genocide came to an end and it was safer to travel, her desire to see if any of her other family survived led her to return to Butare.

She arrived to the city on a bus not knowing if she would ever find family who survived the genocide. It didn’t take long before she came across her aunt, Chantal, who was riding a bike to work.

“I was like, ‘Am I dreaming? Is it my imagination?’” she said.

But it was really happening.

Chantal was so surprised that she froze long enough to fall off the bike. Blandine had to deliver the bad news when she was asked if anyone else had survived.

After their reunion, her aunt told her she should leave the family she was staying with and move in with her to go back to school, which she wanted.

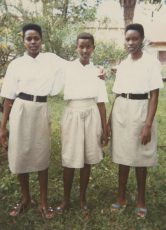

She moved in, returned to school and finished elementary and ultimately continued on through high school. Yet during high school, Blandine’s aunt contracted AIDS and died. Chantal was 27 years old.

“It was hard to understand,” she said. “She was my only one friend. She was my aunt. She supported me. So, to be honest, to be where I am today is because of her.”

As the years passed, Blandine continued to pursue higher education studying law and social science. During these years, she met her husband, Gaspard, a Rwandan whose parents survived the genocide. They got married in 2007 and moved to North Texas in November 2008.

As the years passed, Blandine continued to pursue higher education studying law and social science. During these years, she met her husband, Gaspard, a Rwandan whose parents survived the genocide. They got married in 2007 and moved to North Texas in November 2008.

She transitioned into life as a stay-at-home mom when her son was born. At 3 years old, he was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes, requiring monitoring and care around the clock. She later gave birth to a daughter as well, but Blandine’s drive for education led her once again to search for a school.

She asked her husband for nearby possibilities, and he told her maybe North Lake College in Irving because he had attended there before. Their search led them to find NE Campus because it was closer to home.

However, the educational system was a challenge to navigate for Blandine. She set up an appointment with the counseling and advising office. But language and communication were barriers as she was still learning more English.

Blandine asked if anyone could talk to her in French. This led her to the office of NE counselor Masika Smith.

After learning Blandine was from Rwanda, Masika initially struggled whether she could help her. Masika is from the Congo, and the two countries have a long, difficult history with each other.

In 1994, Masika was living in the Congo, but as a teenager, she didn’t fully understand the genocide as it was happening. A few years after, Masika left the Congo.

Twenty-five years later, the two met across the globe in Hurst, Texas.

“Am I going to be able to work with her?” she first asked herself. “She hasn’t done anything to me. I haven’t done anything to her.”

Masika had a momentary doubt of how she was going to help Blandine due to their backgrounds but soon realized there was no reason that she couldn’t.

“If there are any conflicts, it’s among whoever is having conflicts with each other, but it’s not at your level,” Masika said, recalling advice from her aunt.

Regardless of whether a student is Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa; from Rwanda or Congo; or any other background, Masika wants students to know that TCC counselors are here to work with everyone.

Masika asks herself what can be done to teach people to not let bitterness or hate take control of their lives as well as what should be done to educate future generations.

“What can we do as an institution to start facilitating an environment of healing, peace, reconciliation?” she asked.

This can be done by teaching traits that hopefully will help avoid future atrocities, she said.

“I think if we can raise leaders with critical thinking and empathy, then I think we’ll raise great leaders,” she said.

Blandine, now 36, is currently taking part-time classes with plans to go into a nursing program. Caring for her son motivated that interest.

“In the society we are living in, there are many people who need help,” she said.

From Rwanda to TCC, she’s had 25 years to process and reflect on past events. But after living through the painful legacy of the Rwandan genocide, her focus now is on her family and school.

“I learned how to love myself because if I give up on me, there is no way my family can survive,” she said.