By Alyssa Pate/reporter

Photos courtesy of Netflix

TCC students and faculty have weighed in on Netflix’s newest phenomenon, Making a Murderer, and not everyone is on the same side.

“From an opinion of someone who has only heard about the case, it seems like the filmmaker’s purpose was to sensationalize the case,” NW student Jared Tyra said. “I don’t doubt they made a buck or two off of it.”

Making a Murderer was created by filmmakers Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi over the course of 10 years. The film was released Dec. 18 on Netflix.

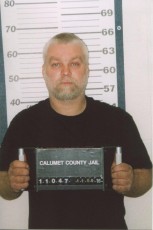

The docuseries tells the story of a Wisconsin man, Steven Avery, who was convicted of sexual assault in 1985. Eighteen years later, Avery was exonerated by DNA evidence. While in a civil lawsuit against the Manitowoc County sheriff’s office and district attorney, Avery was arrested and charged with the murder of 25-year-old Teresa Halbach.

“The evidence against him was insufficient, and from what I’ve gathered, he looks to have been framed,” SE student Shelby Thompson said. “I think the fact that there is ‘possibly’ an innocent man that has spent years and years of his life in prison for crimes he did not commit attracts people. It’s a miscarriage of justice, and the public wants to change the outcome.”

Thompson is not the only student at TCC who thinks Avery was wrongfully convicted and there were problems with the evidence.

“The evidence against him was improperly handled, and there wasn’t enough investigation of other persons of interest,” NE student Michaela Valdez said.

Halbach, a freelance photographer, routinely took pictures for AutoTrader magazine and frequented the Avery property. On Oct. 31, 2005, she visited Avery and two other homes to take pictures of vehicles. She was reported missing less than four days later.

The Avery family cooperated with police and gave the search team permission to enter their property. On Nov. 5, 2005, a search team member located Halbach’s vehicle partially hidden on the Avery property. This find led to an eight-day search of the property where police found Halbach’s car key in Avery’s bedroom, Avery’s blood in her vehicle and her remains in a fire pit behind his trailer.

Avery was arrested and charged with murder on Nov. 9, 2005. On March 1, 2006, Avery’s 16-year-old nephew Brendan Dassey confessed to his and Avery’s involvement in the sexual assault and murder of Halbach.

The confession, which he would later recant claiming coercion, led investigators to search the garage where they found a bullet with Halbach’s DNA. Although the evidence points to Avery’s guilt, his defense team argues that the evidence was planted and that he is being framed.

Avery was convicted of first-degree intentional homicide and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Dassey was convicted of first-degree intentional homicide as party to a crime, mutilating a corpse as party to a crime and sexual assault as party to a crime. He was sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole in 2048.

“The non-blood DNA of the defendant found on the hood latch (under the hood) of the victim’s SUV — this is not only inconsistent with the planting defense, it completely dispels it. … The defendant can’t reach under the victim’s hood if he had nothing to do with her murder,” Ken Kratz, former special prosecutor and Calumet County district attorney, told The Collegian.

“The bullet, with the victim’s DNA on it, matched the gun hanging over the defendant’s bed, when it was seized from his bedroom. So, this means that that gun fired that bullet (before 11/5) and it had the victim’s DNA on it … why did the filmmakers leave all this out of their docudrama?”

Demos and Ricciardi said they left certain pieces of evidence out of their film. They contrasted their documentary against a trial, pointing out that a trial includes all of the evidence while a documentary does not.

Kratz believes most of the evidence was left out to help the filmmakers sway the audience in favor of the defense.

“The filmmakers spoon-fed the audience to only be able to conclude one thing … that there was a miscarriage of justice,” Kratz said. “If both sides of the case were equally presented (like in the jury trial), people would know he was guilty, just like the jury did.”

Since the conclusion of the trial, countless online petitions have been started asking for Avery to be pardoned. One petition on Change.org has accumulated more than 462,000 signatures.

Avery and Dassey have both filed appeals, but have both been denied new trials.

“There are thousands of cases disposed of daily across America, the overwhelming number by plea bargain,” said Brent Carr, judge in Tarrant County Criminal Court No. 9 and NW criminal justice instructor.

“The media rarely covers routine case dispositions. They are always drawn to the train wreck. On some occasions, this results in a wrong being corrected. On others, it is rank speculation that does not stand up to close scrutiny. I am not convinced the general public has a preoccupation with this case.”