Over New Year’s weekend, federal immigration authorities apprehended 121 adults and children in a series of raids aimed to curb illegal immigration.

The raids took place in several states, including Texas, and those in custody were to be deported back to Central America.

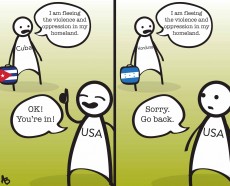

White House press secretary Josh Earnest said the removal effort would hopefully discourage Central American families from sending their children on a dangerous journey to enter the U.S. illegally. The exception, however, lies with illegal immigrants from Cuba.

In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Cuban Adjustment Act in the midst of the Cold War. In a nutshell, the CAA attempted to undermine communism by giving Cuban migrants refugee admission and, in some cases, immigrant visas.

In 1995, the CAA underwent several changes during the Clinton administration known as the “wet foot, dry foot” policy. Essentially, this revision said any Cuban immigrants intercepted in water between the two countries were to be returned to Cuba or a third country. However, Cubans who arrived to shore or traveled to America through another country were still granted amnesty.

The reason Cubans were and are currently still granted amnesty is because they can cite persecution under the Castro regime. Unfortunately for Central Americans, their oppression is less systematic and not government-regulated, and, therefore, they aren’t granted the same privileges Cubans receive.

This doesn’t mean to undermine the hardships many Cubans still face in their homeland, but the days of forced labor camps and political executions seem to be lessening. To be fair, Cubans do not enjoy the same freedoms Americans do. Cubans still face political repression, unjust imprisonment and prisoner torture, censorship and restrictions on the freedoms of women, assembly, education, health care and religion.

By no means should the federal government revoke amnesty for the Cubans who are clearly being repressed. However, the government should no longer turn a blind eye to immigrants in similar dire straits, specifically those from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, countries whose immigrants have been specifically targeted in January’s raids.

Both El Salvador and Guatemala have seen their fair share of repression in the form of violent government suppression, military insurrections and mass killings. In addition, all three countries face the threat of drug trafficking violence that affects both cities and small towns.

Poverty, food insecurity and deforestation make living increasingly difficult if not dangerous for these fleeing immigrants, but still the United States does not see a reason to harbor those in need.

Clearly, the U.S. is fully unprepared to accept all potential immigrants who would hope to flee hardship. The country lacks the jobs, housing and resources needed to properly take care of all potential migrants, or the immigrants would get jobs by undercutting the wages of those currently employed, which would cause a severely negative impact in both the economy and American sentiment toward immigration.

In actuality, we should only let a certain percentage of immigrants in yearly, make sure they are adjusted to society and then do the same next year. However, one thing we should not do is play favorites. Be it Cubans, Syrians or Salvadorians, we should let in an appropriate and fair percentage of those trying to migrate from each country because the answer is not in a wall miles long and high or in an all-come, all-served immigration policy.

Like most things in life, the appropriate response is found in the middle with just a little bit of moderation.