By Katelyn Needham/ editor-in-chief

Peter Matthews/The Collegian

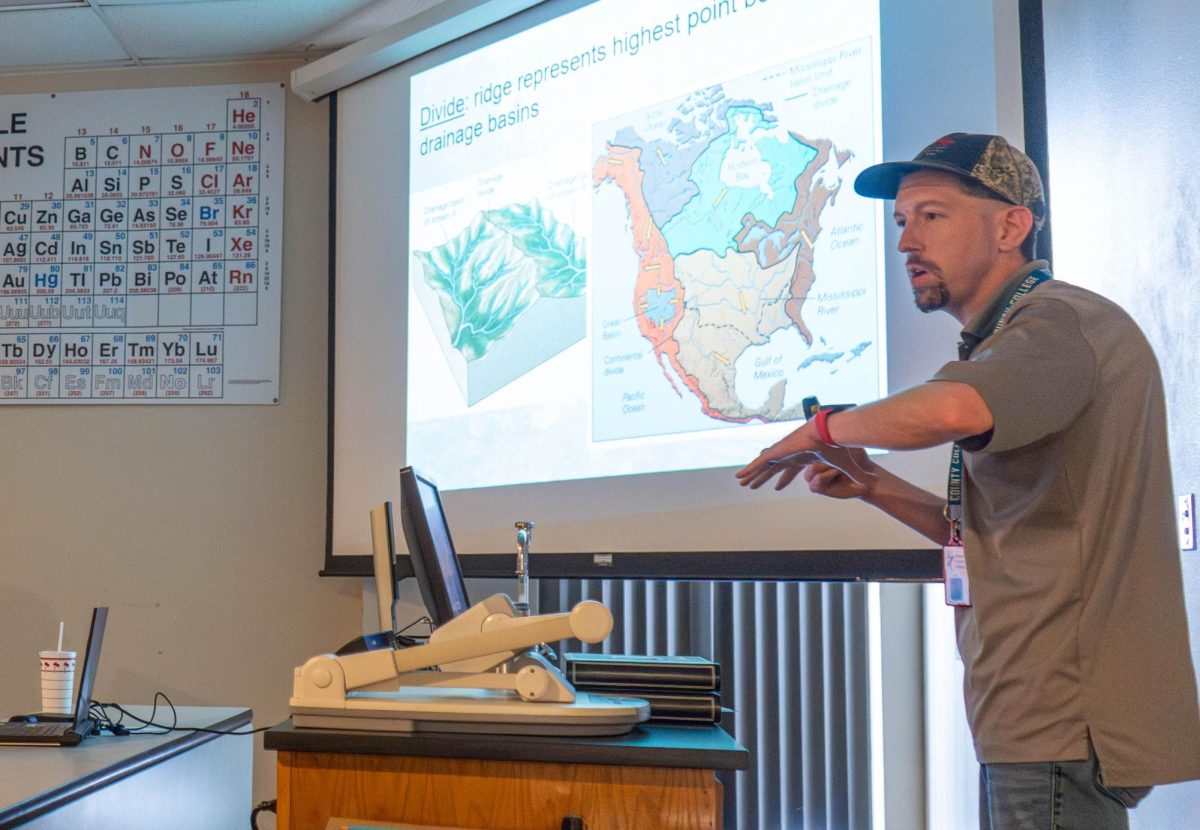

ESEE 2134 on SE Campus is like every other lecture hall.

Anatomy and physiology students fill the seats attentively taking notes, occasionally sneaking glances at the digital clock to see how much time is left.

SE biology professor Hung Vu stands at the front of the room drawing a diagram on the chalkboard of the human torso so he can explain how the botulism toxin paralyzes the muscles. While he draws, he tells stories from his time fleeing Vietnam after the fall of Saigon.

Just by looking, you wouldn’t know that Vu was a political refugee, one whose life was worth only seven bags of rice.

“To get to Thailand, I had to go through the Pol Pot regime on the border of Cambodia,” Vu said. “They hated Vietnamese. They enslaved me about a year and a half. It was brutal. We had to sleep outside with nothing on, and then we would go into the fields and slave there to plant rice.”

Photo courtesy Hung Vu

An estimated 1.5 million people were killed in Cambodia under the Pol Pot regime. The mass graves the victims were buried in are often referred to as the “killing fields.”

“When we got caught by the soldiers, and when I say soldiers, I don’t mean men. Some of them were children, only 16 years old,” he said. “The guns were almost as tall as them. They took us inside and showed us these flip-flops lined up. I thought they were gonna give us shoes but no. We saw a very shallow grave. And they say those right there are dead people, and if you run, you’re going to be right there.”

Vu was only 16 at the time he was captured.

“They don’t kill you with a bullet, nope. That’s a favor,” he said. “Bullets cost money. They make you dig your own grave. Then they line you up along the side and use a shovel to whack you behind the back. They had the skill to whack you almost dead so that you drop into the hole. That was easy for them.”

The International Red Cross eventually freed Vu and other refugees.

“The International Red Cross drove the border every day,” Vu said. “They had a shack that was almost like a clinic. They would give out food and medical supplies. That’s where we were trying to get before we were captured. But the Red Cross doctors came over and said, ‘Those people are refugees. I would like to take them with us.’ To take us, they traded for each person with seven bags of rice. I was seven bags of rice.”

Before Vu was enslaved on the Thailand border, he had to travel over 600 miles on foot, boat and bicycle over the course of 12 days to escape Vietnam. Three of the nine people in the travel group would die before reaching Thailand.

“Most people who left went by boat,” he said. “You could go out into the ocean and find a bigger boat that would pick you up. If you claimed to be a political refugee, they would help you. The majority of people do that, but many of them die because there would be no one there. They would run out of supplies and food and die, and it’s more expensive to go that way. So my mom saved up money to send me through the west side through Cambodia.”

In April 1975 after the fall of Saigon, any government officials associated with the United States were thrown in prison. Vu’s father was one, leaving his six siblings, his mother and Vu to be pushed out of the city.

“We had to make our own house, our own food and try to survive,” he said. “Most commonly, the families that had money would send their sons away. Otherwise, they would make you join the army. The only function they have is to carry materials to support the real army, and most of them die.”

Peter Matthews/The Collegian

Vu’s mother paid a guide 30 ounces of gold to ensure his passage into the democratic country of Thailand. His father and siblings would come to America in 1989 when his father was released after 14 years in prison.

“My life would not go easier if I had stayed in Vietnam,” he said. “I would not have finished high school, and if I did, I would not have made it to college.”

After Vu was freed from Cambodia, he was granted only 45 days in Thailand. He applied to come to the U.S. and was accepted due to his father’s work with the government. Before he could go, he had to spend nine months in a processing center in the Philippines.

“The PC camp gets you familiar with the culture and English so that you don’t experience culture shock,” he said. “I had background in English but just the pronunciation was hard. I remember vividly that when I came over, the doctors with the Red Cross started my interest with medicine. I don’t like the doctors that wear a $200 tie and drive a Mercedes. I want the doctor that’s been in the jungle taking care of you.”

After arriving in the U.S., Vu used programs on KERA like Sesame Street and Clifford to help with his English. He took a year and a half of English as a Second Language classes and other developmental classes at the University of North Texas. When he received his bachelor’s degree, he taught the anatomy and physiology lab there, and his teaching career began.

“It’s where I learned that having English as a second language was not that bad,” he said. “The first time I stood in front of a class, I was terrified. The students even made fun of my accent. I told them they could laugh at my English, but they can’t laugh at my science.”

After Vu got his master’s in neuroscience, he came to SE Campus to teach in 1996. The campus had just opened, and he only taught night classes because he commuted from Denton.

“He’s an extremely positive individual,” math and science dean Thomas Awtry said. “His classes are entertaining, and he has very high standards. I highly respect him. He cares about students but also students learning the material. He uses humor and connections with real life to help make a point. If a teacher can give students a picture, it helps them so much more.”

Photo courtesy Hung Vu

Vu is known as a difficult teacher among students, but SE student Janell Santiago credits his class with her successful study habits.

“I find lectures interesting when you can tell how passionate the speaker is about what they are speaking about,” she said. “You can tell how much Dr. Vu understands and loves teaching A&P through his lectures. I understand A&P pretty well because of him, and I also learned how to study because of this class. This class was very challenging, and you have to study if you want to pass.”

One of the things that Vu is well known for is using stories and real-life situations to explain the class material. He credits his experiences with shaping every part of his attitude and teaching styles.

“You guys say ‘Oh, this is tough,’ and I say ‘No, you can do this,’” he said. “I think it’s a plus for me as well that I can see students in a different way.”