HOPE SMITH

editor-in-chief

hope.smith393@my.tccd.edu

Second grade taught me that there was something not quite right about myself. My report cards were riddled with concerns about my focus, and on parent-teacher days my mother was shown the neatly organized classroom cubbies and had to guess which one was mine.

Her hint was the disorderly chaos box of pens, pencils, odds and ends spilling over the edge that was not like the others.

And just like that cubby, I felt very different. Not in the way people want to be, anyways. I was disorderly in ways that teachers were concerned about.

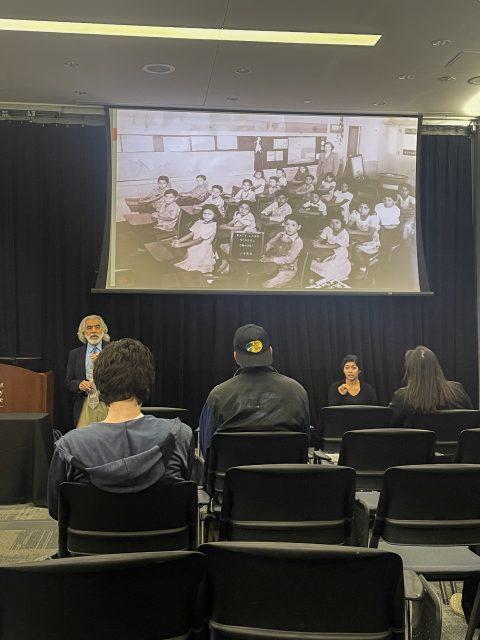

I knew something was not quite right with me when I was eventually placed in a small focus group. I knew when I stayed there three years later, when time fell through my fingers like sand, when I watched my peers get separated into classes for those better at school than others and I was not in that group.

So, as a child, I decided something was wrong with me and that no one could really tell what. And that was a big problem, which made me a big problem. And I lived thinking like that.

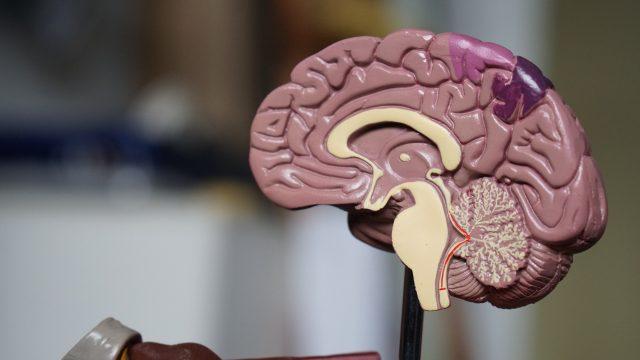

I was seventeen when I was diagnosed with ADHD. I had already spent most of my life believing that my symptoms were a result of something terribly wrong with me, so this diagnosis was both relieving and horrifying. My “wrongness” finally had a name, but I had grown up with it completely untreated.

The thing is people are not made defective and mental disorders don’t make you any less deserving of a happy, successful life. I was not wrong for the way I was. I was a child operating in a world that hadn’t yet explored how ADHD looked in young girls. I did what I could with what I knew.

My symptoms were not the typical obvious hyperactivity, it was subtle. I was easily distracted, talkative, forgetful. All these things just seemed like they were a “Hope” thing. Something about it all made me think I just grew wrong, like a tree warping around its obstacles.

I did not see it as something quirky or silly. I hated my “Hope” thing that made me disorganized, late, forgetful and distracted.

I tried every day to be anything but that so people wouldn’t see how imperfect I really was. That reality was terrifying, because it could confirm every bad thing I thought of myself since I was eight.

I wish I could’ve gone back in time to tell myself as a kid that just because I was not advanced did not mean I lacked worth or importance.

Coming to the realization that nobody is normal was the best thing that could’ve happened to me, because it took me outside of my own perspective. Absolutely nobody is the model citizen or the perfect human being.

There are so many people like me out there that my own problems are hardly world-ending serious. Everything I deal with, someone else has. What matters is how I navigate my life knowing I am not neurotypical.

Differences in how you function does not define your place in society.