By Shelly Williams/editor in chief

Editor’s note: The story below may be triggering to those who self-harm. If urges to self-harm arise, please seek help.

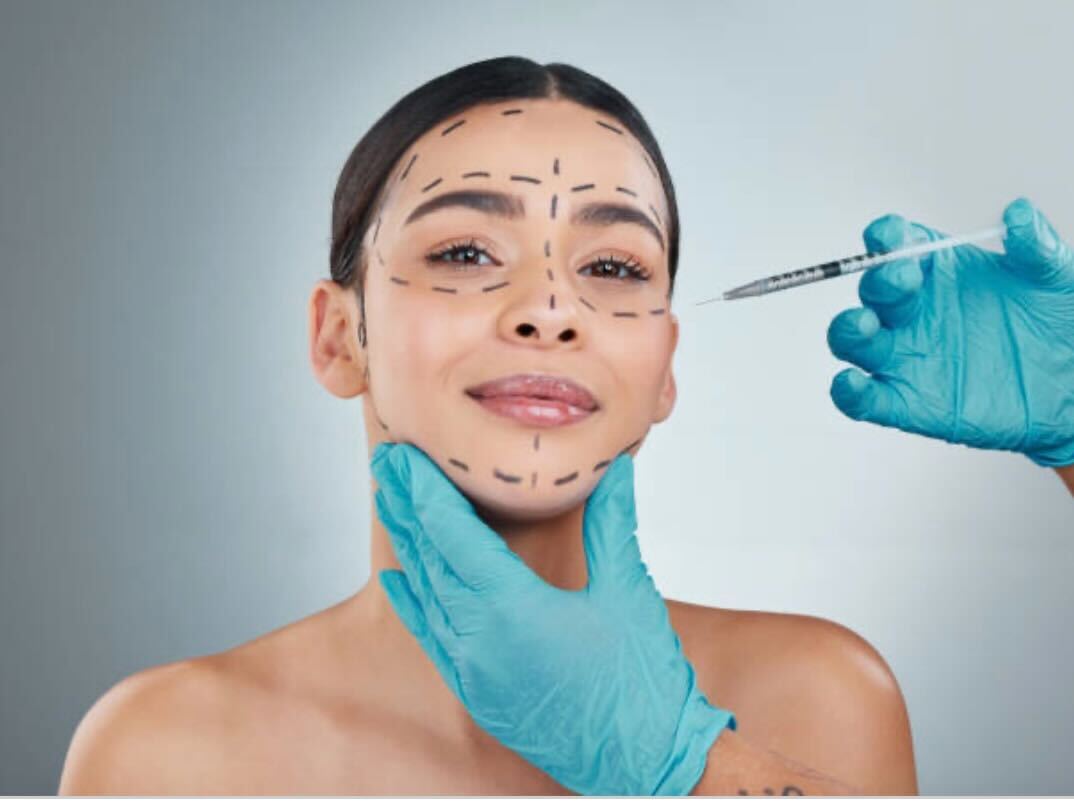

It’s been a while. Occasionally, there’s still an urge to do it. But she’s learned to control herself, NE student Natalie Cener said as she runs a hand over her marked arms.

Cener will be 23 this month. She stopped cutting herself when she was 18, but it was a part of her life for eight years before that. She has about 150 scars that tell her story.

“Before, I couldn’t stop myself. I’d just end up doing it, and I didn’t even realize I would do it,” she said. “Now, I just take a couple of breaths. Maybe play my guitar for a few minutes and just chill out.”

She is one of an estimated 2 million in the U.S. who intentionally injure themselves through cutting, burning, pulling hair or other ways, according to the Mental Health America website.

“People who cut do feel strong emotions that they don’t know what to do with, so they turn that emotional pain into physical pain,” said Patti Bolle, a licensed professional counselor in Southlake. “It’s a way of controlling emotions that they don’t know what to do with.”

Bolle, an expert in self-injury counseling, said self-harm mostly begins around puberty. Trauma and lack of a stable family also play big parts in the start of self-injurers.

For Cener, it was her father.

“He is ex-Army. He used to hold a lot of things in, and he’d come home,” she said. “He’s not going to hit the wife. The wife will leave his ass. He’s going to hit the kid ’cause the kid can’t do anything. I was his outlet.”

At 10 years old, Cener was walking on eggshells in her home. She said he could be the nicest guy in the world, but it took only a little tip to push her father over the edge, turning him into “the worst terror in your life.”

“He’d hardly use things. It was always his hand,” she said. “He used to say, ‘If I know it hurts my hand, I know it’s hurting you.’”

But it was the bruises and occasional cigarette burns from her father that pushed Cener over her own edge.

Being a military child, Cener moved around a lot. She was an only child. So her pets became her world, or the closest friendships she had to the real thing.

But with a dog that constantly tore up the backyard, she said her father thought it best to get rid of her best friend.

“I freaked out. I didn’t know what to do,” she said. “I packed my backpack, took my dog, and I took off for two days. I was 10 years old.”

Two days later, she returned home, received a beating and was told she’d be sent to military school no matter what she thought, she said. Only he used more explicit words.

This was Cener’s breaking point. She said she wasn’t aware of what she was doing, but she’d taken a razor to her skin. After her first cut, her mind awoke to the sight of blood.

“I was freaking out because I was bleeding,” she said. “It wasn’t something huge, just a scratch. But the little bit of blood was like, ‘I did that.’”

Growing up, Cener was sheltered, she said. She didn’t watch TV, much less like it. She said she had no idea other people self-injured. This made her feel completely alienated, so she’d hide her cuts more with long-sleeved shirts, even in the summer. And she would make up excuses, like she cut her arm while she was outside playing or she had bandages meant to cover a rash that never existed, something Bolle described as common.

“The way a lot of self-injurers hide it is by becoming wallflowers, not joining in activities that would make them feel good and get endorphins going. They tend to wear baggy clothing to hide their bodies,” she said. “I wouldn’t even categorize the ‘Emos’ as cutters. It’s not the same.”

Cener’s frustrations escalated. So did the cutting. Moving around so often meant learning to not get attached to people she cared about. As she entered adolescence, her sexual orientation became just another way she felt alienated from everyone else.

“I knew I was different,” she said. “You know how you play house when you’re a kid? Well, I wanted to be the daddy. Being the mommy was just weird for me.”

With this internal struggle also came the external struggle of dealing with bullying in school. Cener faced fights, and peers called her a “fag” or “dyke,” but she wasn’t allowed to cry about it, she said.

“I was my father’s daughter, but I was also his son,” she said. “He’d often say, ‘No daughter of mine is going to cry.’”

After a while, she said it came to using whatever she could find to get the relief she wanted. Cener would break shavers to reach razorblades. She’d take apart diabetic testing strips to get to sharp needles. At one point, she used a knife.

Cutting was her way of dissociating from life, she said.

Cener remembers her worst time when she was 15. She doesn’t remember doing it, but she remembers the blade sticking out of her skin.

“I remember coming out of it, and there was a knife in my leg,” she said. “I’ve got this scar that’s two inches long on my leg. I had to have 15 stitches. On the other side, there’s about a half-inch scar from where it came out.”

That’s when her parents realized Cener needed help. She was sent to therapy, leading her to open up and talk about the emotions inside.

“Then there’s the whole stigma of you going to a therapist because you’re crazy,” she said. “It took a long time before I got comfortable enough to really open up about some issues. The whole process was hard — an uphill battle. Very uphill.”

Bolle said this stigma is where many people get stuck when it comes to reaching out for help. Self-harm is also something that is hard to stop because it’s hard to let go of, she said. Many think that it’s the only way to cope because it’s all they know, she said.

“First of all, talk to somebody because we’re not here alone,” she said. “I think everybody’s got self-deprecating stuff that they deal with. Most people won’t call it self-injury because they’ve got it under control, but any kind of addictive behavior that’s not healthy for your body is considered self-injury.

“I get so many people sent my way, and they just want to hear that it’s OK, that they’re not perfect, and to take a breath. And let’s start one step at a time on this road to recovery, and let’s get past this. Everybody’s walking around with their skeletons, but none of us are perfect.”

Cener has been cut-free for almost five years. Her family’s relationship is improving. She’s engaged to her girlfriend of seven years and is planning a trip to Massachusetts to legally marry her partner. And her family, she said, even says, “I love you guys,” at the end of every phone call.

But self-harm isn’t an issue that happens only to teenagers, Bolle said. If hidden well enough, if ignored long enough, she said it could go into college, post-college and even marriage.

“You have to be ready, and you have to be aware that your coping mechanism isn’t healthy. Then you have to accept that you’re flawed,” Bolle said. “And then you have to be willing to try other things, other alternatives and move away from your old habits.”

So Cener will have to continue her uphill battle, fighting off the urges that occasionally still haunt her mind. To those who may be struggling with self-harm, she said it’s best to reach out for help.

“I’m not a good advice person, but even if you’re afraid or not, it’s always best to talk to somebody,” she said. “’Cause if you’re a cutter and nobody knows, you could be dead the next morning. You need somebody watching your back.

“I needed that when I was going through that. Nobody watched me for the longest time. Nobody knew. And I have all the scars that I’ve got to deal with now.”

Help & warning signs

Outlets for those who need help:

ω S.A.F.E. Alternatives (Self Abuse Finally Ends) — www.selfinjury.com, 1-800-DONTCUT

ω To Write Love on Her Arms – “a non-profit movement dedicated to presenting hope and finding help for those struggling with depression, addiction, self-injury and suicide. The movement exists to encourage, inform, inspire and also to invest directly into treatment and recovery.” Visit www.twloha.com for more information.

Warning signs of risks for self-injury:

Unexplained cuts or bruises

Trouble handling emotions, especially sadness, fear and anger

Low self-esteem as evidenced by a tendency to self-denigrate

Arms and legs always covered

Presence of an eating disorder or possible substance abuse

Suggestions for helping someone who self-injures:

Parents should not react intensely (such as fear or anger).

Threats (such as grounding) and rewards (such as later bedtime) are rarely effective.

Do not ask “Why are you doing this to me?” or even “Why did you do that?”

Speak to the person calmly, and non-judgmentally while expressing love and concern.

Listen — don’t try to offer an opinion or “fix” the problem but try to foster open communication.

Educate yourself on self-injury to better understand where the self-injurer is coming from.

Tell the person you are concerned and that the person can talk to you about anything, and then follow through with that.

Source: S.A.F.E. Alternatives, www.selfinjury.com