By Michael Foster-Sanders/campus editor

Policing tactics lead to fear, anxiety among minorities

Gemeral Berry was sitting in the car in front of his house talking with a friend when he was swarmed by law enforcement thinking he was a suspect in a string of robberies around his neighborhood.

“Four police units came from three different directions, and we’re sitting there. A unit parks behind us with the lights on, and there are two units in front of us,” the NE journalism adjunct instructor said. “The officer asks me for my driver’s license. I asked them why did they stop, and the officer said, ‘There have been burglaries in the area, and we were checking out strange people.’ And I told the officer, ‘If you look at my driver’s license, you will see that I’m in front of my house.’ The only thing the officer said was, ‘Here’s your ID.’”

Even though this happened years ago, Berry is still agitated telling this story. He pointed out a lack of trained empathy on the officer’s part. He felt the officer thought he was above giving an apology for a misunderstanding.

“What I am annoyed at still today is that officer should have at least said, ‘I see you’re here at your house. Sorry for the inconvenience. Have a good night,’” he said. “That officer said nothing. And that’s a problem.”

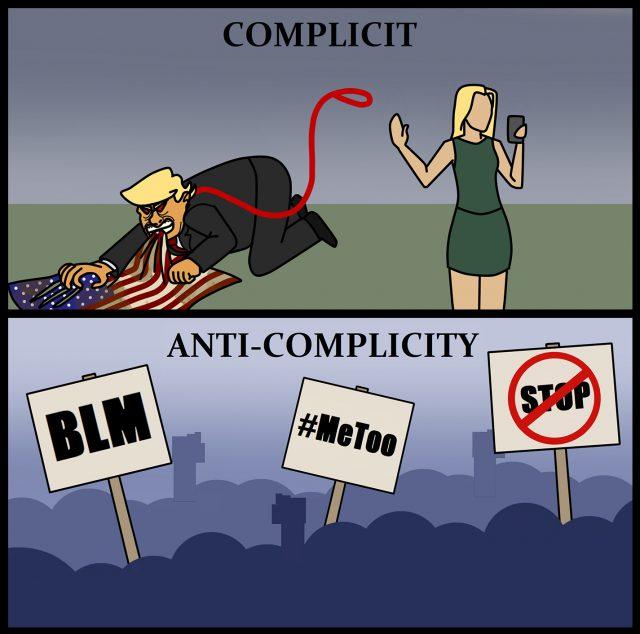

After a string of racially charged incidents involving law enforcement received national attention, minorities in the TCC community shared their experiences with police. While they said not all police behave badly, their experiences have shaped a mistrust that hasn’t gone away.

NE student Cameron Davis feels like a change needs to be made to how law enforcement interact with minorities after an incident with one suburban officer.

“I felt he only did it because I was black,” Davis said. “Police should give minorities an equal chance when policing instead of policing by stereotypes. I feel that racism is still intact.”

Davis was at a high school football game hanging with friends when he went to get a drink of water. While going down the stairway with friends, he passed a police officer who accused him of bumping into him.

“This white police officer said I bumped into him, but I didn’t,” Davis said. “The officer said did I want to get kicked out the game for bumping into him and threatened me with having to pay higher ticket prices to come to future games.”

Even with Davis’ friends telling the officer that he didn’t bump into him, he was kicked out of the game and given a citation. Davis filed a complaint against the officer and is waiting on a response from the department.

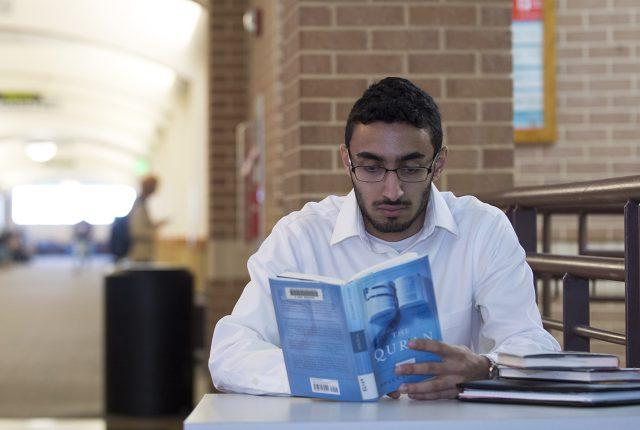

NE student Isaac Sigala said he was a 9-year-old child when his view of law enforcement changed during a traffic stop with his father, sister and a family friend.

“My dad was pulled over, and he had drugs on him, and his white friend tells him to give him the drugs and don’t worry about it,” Sigala said.

Sigala, his father and his 7-year-old sister were searched for over an hour and a half, but the police didn’t search his father’s friend.

“He had the drugs in his boot and was holding a conversation with the officers without being searched,” he said. “That stuck with me.”

Sigala said he’s never had a good interaction with police but still has faith in law enforcement and believes training could help alleviate issues with minority and law enforcement interaction.

Berry echoed the same sentiment about police going through training.

“Are the police being trained properly to interact with the public?” he asked. “One of the things I think happens too many times is those officers are not for diversity. Or if so, they don’t take it seriously.”

Stanford University’s Open Policing Project found evidence linking prejudice to why police require far less reasons to search black and Latino drivers than their white counterparts.

The largest traffic stop study completed looked at more than 60 million police stops in 20 states from 2011 to 2015. It found blacks and Latinos were twice as likely to be searched during a traffic stop than whites. Blacks were 20 percent more likely to receive tickets than whites, and Latinos were 30 percent more likely to receive tickets than whites.

NE radio/television/film instructor Adrian Neely knows about being racially profiled, or “driving while black.” His story is about an encounter late night on an Elgin, Texas, highway.

“I was pulled for doing 51 in a 50,” he said. “The officer asked me could he search the car. Was I supposed to tell him no? It’s dark, and it’s pretty late. It was cold outside while I was waiting for him to get through searching the vehicle. He let me go after, but 51 in a 50 and searching my vehicle was enough for me.”

Sigala explained the unwritten rules that minorities have to know when going through small towns with a high chance of being racially profiled.

“When you’re driving through Hurst and you’re a minority, you know not to be ‘riding dirty’ and have everything in order because Hurst is not the place to be messing around,” Sigala said.