By Kenney Kost/editor-in-chief

When an elderly man strolled into NW administrative assistant Kathy Saburn’s office, there was no way she could have known the scope of the story she was about to hear.

“When he said he was 96, I wanted to know his story,” she said. “And what a story he has.”

NW continuing education student Peter Belpusi has many stories to tell from his 96 years. The one thing that has stuck with him since he can remember is his love of art. This love of art has led him full circle back to school to continue perfecting his craft.

“It started from reading fairy tales, and then I would try to draw what I imagined,” Belpusi said. “We did a little art in grade school, but it wasn’t until high school that I got more serious and was able to take more art classes. I did my first painting using a nude model when I was 16.”

Directly out of high school, Belpusi went to the Cleveland School of Arts where he could put all his energy into his art. From 8 a.m. to around 4 p.m. every day was spent in various painting, clay working and drawing classes.

“Art school is not like university where you have academics most of the day and take one ceramics or painting class per semester,” he said. “It was all-day art and then homework projects.”

For five more years, he would attend art school in Cleveland and the Art Institute of Chicago. Then, in June 1941, life would change dramatically as he was drafted into the Army.

“We [U.S.] had not entered the war at this point,” he said. “But [Franklin] Roosevelt started the draft prior to entering, and we were to serve one year. Art school students were not exempt. Seniors at a university were exempt until they graduated.”

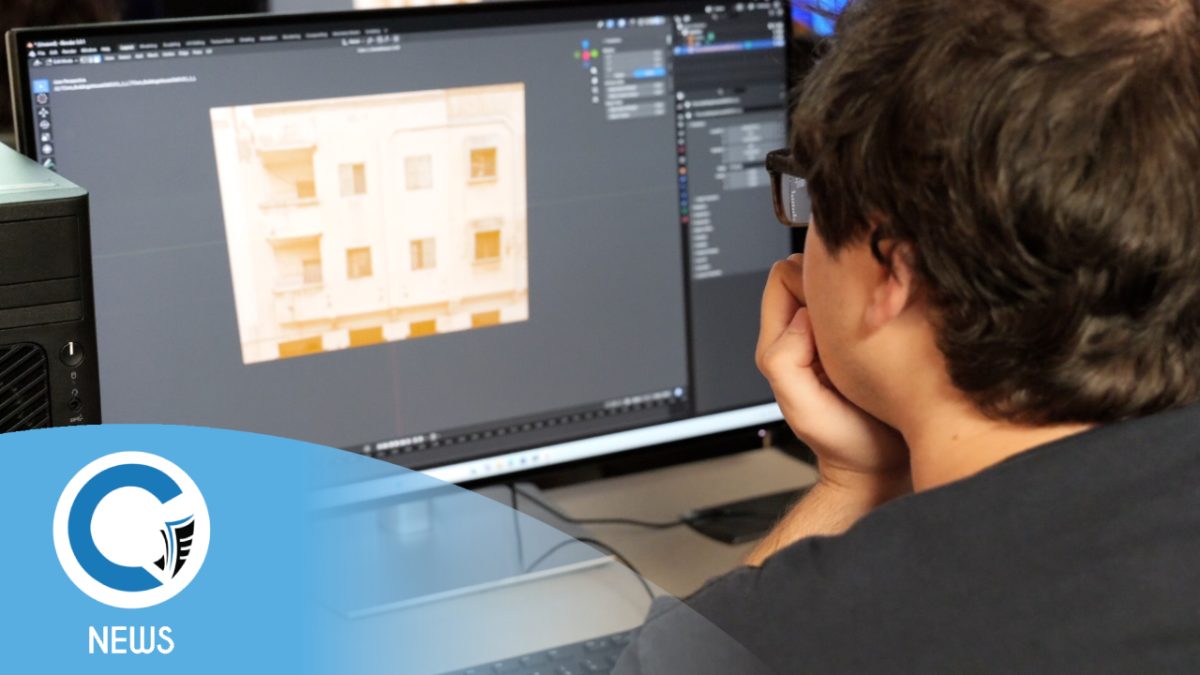

Little did Belpusi know, the one year was about to turn into more than four years when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entered the war in December 1941. Belpusi fought in five campaigns across Europe, serving in the 4th Armored Division Tank Artillery under Gen. George S. Patton in the Battle of the Bulge among other battles.

“I was right in the middle of it,” he said. “When you see a tank and the round comes out of the barrel of the tank, and you hear the whistle of the round coming out of the barrel and the explosion of it hitting at the same time all around you, you know you are in a battle.”

Belpusi was also at the battle of Normandy, though not the initial D-Day siege.

“Once they established a beachhead, about three or four miles, we set up these pontoon bridges for our tanks to cross into Normandy,” he said.

The break from art was a blessing in disguise at first, and Belpusi was so engaged in the military and the war he didn’t have time to think about painting for the first two years. Then, strep throat forced him into a military hospital.

“While I was in the hospital, I got the urge to paint and asked the nurse for watercolor paper and paints,” he said. “I had finished one and was just going to throw it away and start another when the nurse stopped me and said she liked it so much and asked if she could keep it.”

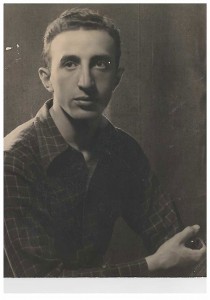

![NW student Peter Belpusi shown [middle] with his crew during World War II. The tank and all crew members survived five European campaigns totaling 4,000 miles including Normandy. Photo courtesy Peter Belpusi](https://collegian.tccd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/10092013OldPeter-300x231.jpg)

“I married her just before I went to Europe,” he said. “I married her so nobody else would when I was gone. I loved her and knew it.”

After the unexpected stay in the Army, Belpusi was ready to get out and finish art school. So in 1945 after the war, he did just that graduating from the Art Institute of Chicago in 1946.

After graduating, he taught art at Lake Forest College in Illinois for 10 years and then in Chicago public schools for another 25 years before retiring. During this time, his wife also taught art around Chicago, and the two of them ran a ceramics company named Wheeling Ceramics.

“I loved teaching,” he said. “I like to be around people, and I just love my art you know. It’s fun, and I wanted to pass that along. The ceramics shop was another outlet for us to focus on our art. Not to mention, we made a lot of money.”

After 35 years of teaching and working the ceramics company, the two decided to retire, sell the shop and buy a farm. They purchased an 80-acre farm in Missouri in the early ’80s. Belpusi was 63 at the time and said he just wanted to relax, paint with his wife and enjoy nature.

With help from neighbors around the area, the two ended up with 40 head of cattle by the time they sold the farm in the 1998.

After a while, he realized he hadn’t been doing much to stir the creative juices. Being so busy with the farm, he said he lost sight of why he bought the farm in the first place, which was to have the freedom to paint and work on his art. So after some thought, he decided to try his hand at writing a book. He wrote his autobiography, A GI’s View of World War II, which is available at the Walsh Library on NW Campus along with some of his translations of Shakespeare including Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra.

“I was looking for inspiration for a novel I was attempting to write on the life of Jesus Christ, and my wife suggested I read Julius Caesar for inspiration,” he said. “It was written in Shakespearean language, so I began to translate it, and before I knew it, I had translated four acts.”

When he showed them to his wife, she suggested they try to publish the work in a dual-column fashion with Belpusi’s translation right beside the original on the page. Once they got it published and bound, they went to the local schools and sold them, he said. This prompted him to do more, eventually translating 16 volumes worth of Shakespeare’s work and selling them around the country.

“We went everywhere,” he said. “We saw Florida, New York, California and everywhere in between.”

The two of them would plan camping trips along their route and would visit as many schools as they could in an area on the way to a campsite, set up camp, eat, sleep and do it all over again the next day.

“It was fun to travel like that around the country,” he said. “We would hit seven or eight schools in a day and around 30 on a trip. Of the 30 schools we would hit, 15 or so would buy the books. So it was a nice deal.”

This went on for about 10 years until around 1994 when his wife came down with Alzheimer’s disease, Belpusi said. He took care of her himself for about eight years on the farm, but it eventually became too much for him.

“It’s gradual, you know, she would forget small things, but it gets to a point where it is just too hard,” he said. “One of my four daughters, Roberta, suggested I come to live with her in Saginaw. So I sold the farm and used some of that money to put an addition on her house and moved in around 1998.”

Nathlie Belpusi died in 2003, and Belpusi fell into a bit of depression.

“I didn’t advertise my depression or anything, but I was a little depressed after she died,” he said. “I pulled out one of my paintings, and it was brittle and looked really bad. So my daughter and I rematted and framed it, and the painting came to life.”

For the next six or seven years, Belpusi worked on framing his entire collection of works, between 600 and 700 pieces and putting them in climate-controlled storage. It was at this point that his daughter told him about art classes for senior citizens at Tarrant County College.

“I said, ‘I’m too old,’” he laughed. “And she said, ‘No, no, no. You can join the senior citizens classes they offer, and it doesn’t cost anything.’ So I took a painting and ceramics class. That was about four years ago, and here I am still taking classes.”

During his time on NW Campus, he met art professor Eduardo Aguilar and began discussing his stockpile of art.

“Some of the students had begun asking me if I could curate a show for his 100th birthday,” Aguilar said. “I said I don’t know for certain if I would be here in five years and said we could reasonably do one for his 96th birthday, which was this summer.”

Aguilar knew Belpusi had a lot of work compiled, but he had no idea what was in store.

“It was a daunting task,” he said. “There were over 500 works in that storage facility, and I had to get it down to 30 or less.”

Aguilar said it was good for Belpusi to get his work displayed, and the student body really enjoyed getting to see how he progressed as an artist throughout his lifetime. Aguilar said he can see that Belpusi enjoys the atmosphere of being around students and having a space to be creative.

“If you are creative, you have to create,” Aguilar said. “His body may be old, but his spirit is young.”

Belpusi agreed.

“I love my art,” he said. “I’m glad they gave me the one-man show here this summer. Everything I do is from my own life and artistic experiences. When you spend a year and a half on the battlefield, from Normandy all the way through the war without a break, it has a powerful impact. My art helps me express experiences like that from my lifetime.”