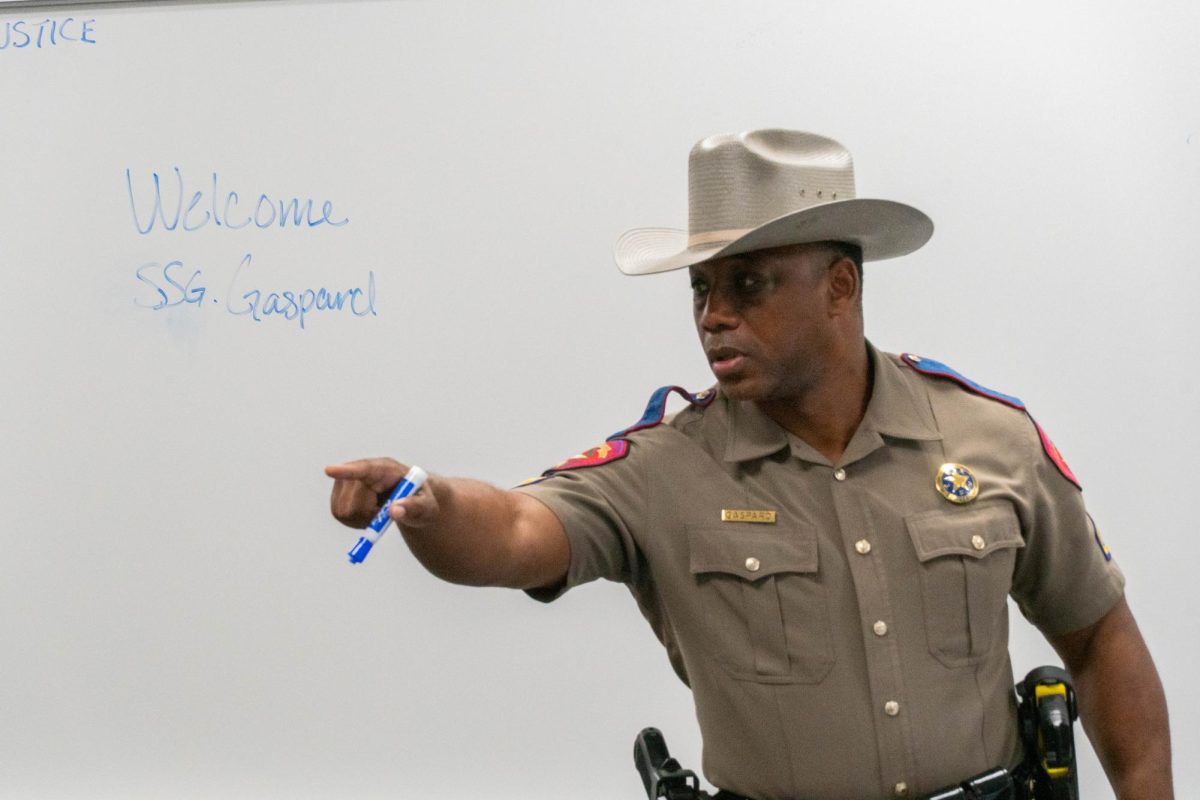

By Anderson Colemon/reporter

Photo courtesy Edward Larson

World War II and Afghanistan veterans shared their experiences during a Veterans Day celebration Nov. 6 on NE Campus.

Edward Larson, now 88, served as a C-46 pilot from 1942 to 1945, enlisting at the age of 17 and remaining in the reserves until 1956.

“I’m humbled by the fact that I was asked to be here,” he said. “For the last several weeks, I’ve been trying to stretch back over 70 years. This isn’t an easy thing to do. It is mind-boggling.”

Larson described as “romantic” his travels to North Africa, China and Brazil. His time in Natal, Brazil, was especially memorable.

“I was in Natal for about two weeks until the rest of my outfit showed up,” he said. “I was happy because it was completely filled with fine beer, beautiful girls and good cigars. And even though I was 18, I was quite impressed with all those things.”

Some of his least favorite trips were those across the South Atlantic to Ascension Island, a stopping point on the way to Africa.

“The airplanes we had then weren’t exactly thrilling,” he said. “The wind blew through them like someone left the window open. It was quite an adventure to try to find the airport at Ascension Island. The island was only about a mile and three quarters or two miles long, and the runway was on a hill.”

The first time Larson truly felt he was in a war zone was the moment he walked off the plane into Al Fashir, Sudan.

“There were British bases all through the North African campaign,” he said, “squadrons of bombers and hurricanes. It was primitive, dusty, dirty and hotter than hell.”

Larson’s final overseas assignment was to carry a group of Japanese prisoners to a surrender ceremony in China.

“It was a tremendous honor to get to participate and be a part of that,” he said.

After the ceremony, it was time for Larson to return home, but he made the journey by ship, not airplane.

“Coming home was a trip,” he said. “It took 32 days to get to New York City.”

The voyage seemed even longer, he said, because of disease and storms in the middle of the North Atlantic.

Once home, Larson could not get the war out of his mind.

“Strangely enough,” he said, “the men I worked with during the war had gotten so close and we became so emotionally involved with one another that they were my family.”

Larson closed with his hope for a better future without war.

“I don’t want any more wars,” he said. “I don’t like them. At 88, I’ve seen enough. I hope that a time comes when we will be past all this.”

Brian C. Fleming, who describes himself as “the blown-up guy,” joined the Army right out of high school and deployed to Afghanistan in 2006. He was twice the victim of explosions.

“While in Afghanistan, I was blown up twice, which isn’t a lot,” he said. “I had a friend in Colorado who has been blown up 16 times, and by looking at him, you would never know anything had happened to him.

“My point is this: there are probably more veterans with extreme experiences, and I’m proud of them. They come back to school, and they try getting their lives back again.”

Fleming’s first bombing occurred only a month after his arrival in Afghanistan. The second took place in July 2006 when a white van driven by a suicide bomber exploded close to Fleming’s vehicle. He remembers only waking up in a ditch, having no memory of the actual blast.

After a long recuperation because of third- and fourth-degree burns and a short-term memory problem, Fleming returned to the U.S. to receive his Purple Heart and a Texas Purple Heart license plate – “NiceTry” – referring to the suicide bomber who tried to kill him.

Fleming created a website, www.Blownupguy.com, dedicated to helping other wounded vets.

“I don’t regret getting blown up,” he said. “It’s a privilege to be alive. I wouldn’t be where I am now or who I am now.”

The celebration closed with William Cobb of the Veterans Administration telling veterans there’s always a place to go and a person to talk to if needed.