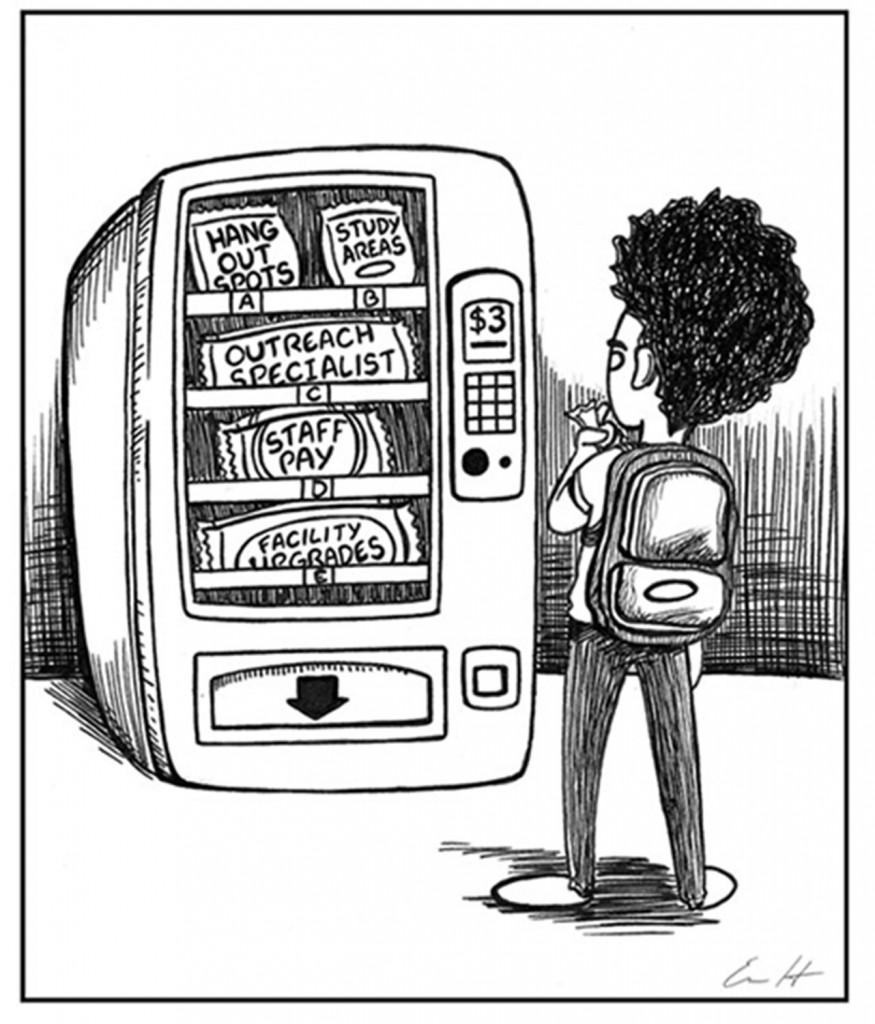

By Mario Montalvo/multimedia editor

Con artists are stealing financial aid money out of the pockets of unsuspecting college students.

According to an article in The Chronicle of Higher Education, students will apply for Pell Grant funds and then enroll in classes. After receiving grant money, they won’t attend class or flunk out but still keep the award money. The culprits are called “Pell Grant runners” or “stipend chasers.”

Runners target community colleges with lower tuition because the payout is highest, the article said. Because these colleges cannot check previous academic records, runners can repeat the scam up to nine times.

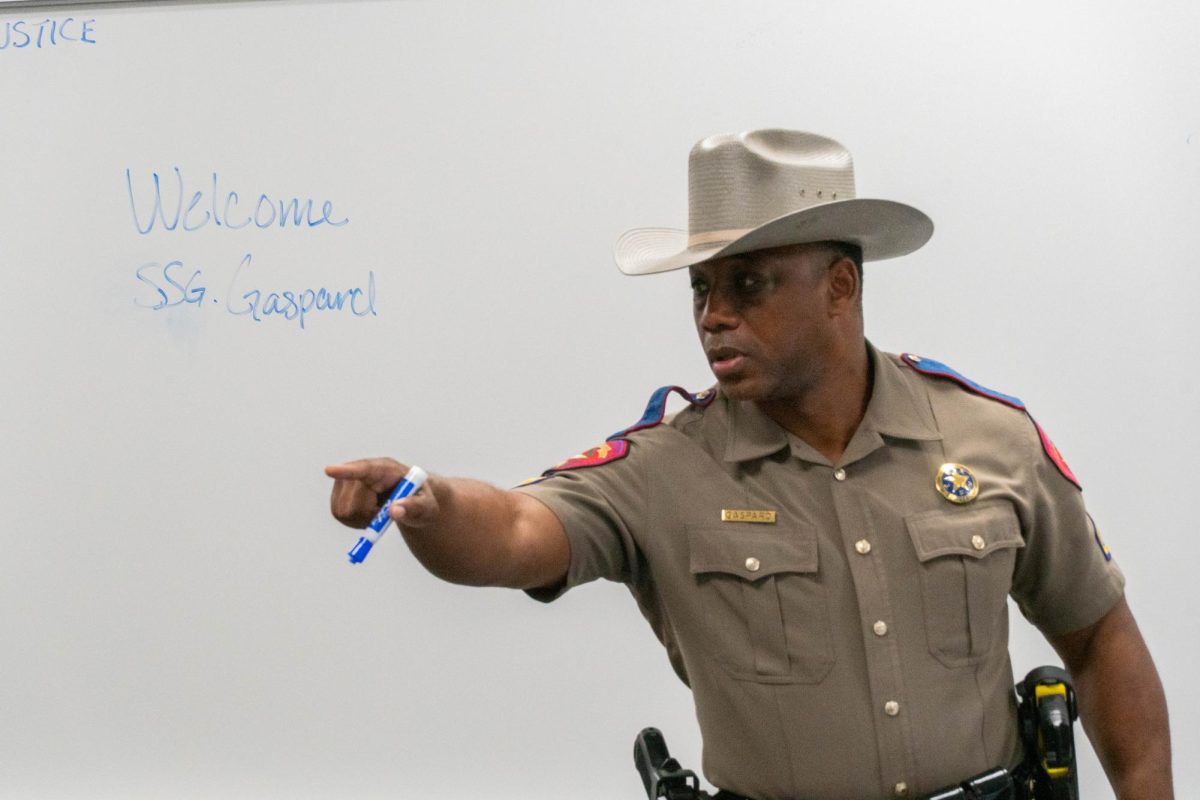

TCC students are required to provide college transcripts from all previous institutions, said district director of financial aid Samantha Stalnaker.

“They certainly have to tell the truth,” she said. “If they don’t tell the truth, we don’t know that they’ve attended another college.”

Some schools are taking steps like disbursing awards through installments to deter runners. Other schools are starting students with poor academic histories on academic probation and withholding funds until their grades improve.

All TCC students receiving financial aid are required to meet certain academic standards to be eligible, Stalnaker said. They must maintain a minimum 2.0 GPA and complete a certain percent of the classes they attempt. If students withdraw from or fail all of their classes, they’re suspended and become ineligible for future financial aid, she said.

“They can’t just register for classes and drop all but one to get an A,” she said. “They actually have to be completing their classes moving toward the degree to be successful.”

In some cases, students may have to pay back some or all of the money they received. If they received financial aid before classes begin but never attended, students are responsible for repaying the funds to the U.S. Department of Education, said NE financial aid director Consuela Mitchell.

Teachers can drop students who miss class. If they get dropped before completing 60 percent of the class, they must repay the money. If they fail to pay, they will not be eligible to collect financial aid anywhere in the country.

Stalnaker said the school runs its own reports and tries to keep track of students who don’t attend class.

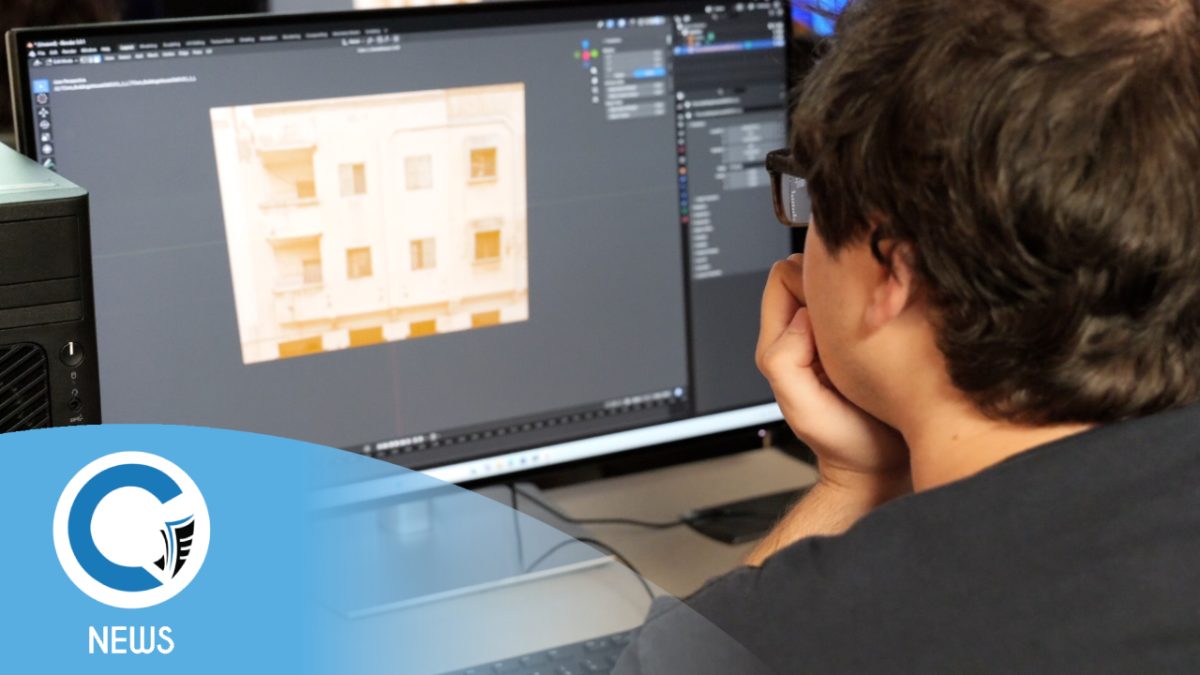

With the increasing popularity of online courses, tracking student progress may be more difficult, said NE student and Pell Grant recipient Juan Olivera.

“You could just pretend you’re doing your work and then take the tests, fail them and then you won’t have to pay it back,” he said. “You don’t have to show up for anything. It’s all online.”

Mitchell said she has not encountered any Pell Grant runners on NE, but Olivera said he knows students who have abused their financial aid in a similar way.

They spend the money on expensive clothing or going out instead of on tuition and books, which takes money away from students who actually want to succeed, he said.

As well as taking money from legitimate students, the practice takes away seats in classes that would otherwise go to students needing to take those classes.

Students who never attend classes also cause a decrease in enrollment numbers, Mitchell said.

Only about 10 percent of students receiving financial aid are placed on suspension, Stalnaker said.

“Because of that, 90 percent of our students get the money. They use it, they’re successful and they’re fine,” she said.