The Paleolithic era is known for the massive amounts of technology and history derived from that period. The wheel. Fire.

And art?

When ice was more prevalent than grass or trees, when saber-tooth tigers were at the top of the food chain, untamed men and women were drawing, carving and sculpting.

Deep in Europe and the Middle East, caves, some still hidden, are full of treasure — not made of gold, bronze or silver, but ivory and bone. The treasures depict ancient creatures one can only read about in history books or see in sci-fi films.

“They were very intelligent,” said Joshua Goode, South Campus fine arts chair. “They had the same capacity for thought that we have now, and so it’s already that important when you’re getting attacked by cave bears and saber-tooth tigers to go in and make art in these deep recesses in the caves because it wasn’t all up at the front. It’s down deep into the caves where few people would go.”

From past explorations, archeologists have found cave paintings 10,000 years older than ones found before, he said. They are more complex and sophisticated than the newer ones.

“It shows they are not progressing, as far as we’re able to represent things better as we learn more. It’s that we’ve always had that skill to be able to represent animals and profiles and complex things,” he said.

Goode was awarded the Dozier Travel Grant by the Dallas Museum of Art to trace the Paleolithic man across Europe and the Middle East this coming June. He will join an international group of archeologists in southern Germany for two weeks. From there, he will travel to France and northern Spain, where he will exhibit some of his former pieces and work on printmaking before heading to Bahrain, an island in the Persian Gulf.

Goode will excavate the Vogelherd cave in Germany, which has in the past produced famous ivory and bone figurines of animals like deer or rhinoceros. He said he hopes to uncover Venus figurines he has seen in pictures.

“Where I’m going, there aren’t as many cave paintings. There are some carvings in the cave, but it’s mainly the little sculptures, and they pre-date the paintings, which I find very interesting,” he said.

The dig consists of descending deep into the cave and hauling dirt and remains out to water screenings. Goode said he doesn’t mind doing the grunt work because it allows him to see everything coming out. Though the cave conditions are different now than when they were inhabited, the art possessed by our Cro-Magnon ancestors remains perfectly preserved in the ground.

“They have found the earliest link to man in the Middle East instead of Africa, a very recent discovery, and I’m talking to archeologists right now about hopefully gaining access to see some of that,” he said. “They just keep finding earlier and earlier examples of art, and it keeps changing our understanding of how art was created and why.”

From an artist’s standpoint, Goode said his excitement comes from thoughts of the opportunity to hold something that was made then.

“We’ve seen images in books. We read about them

and see the movies, but until you actually descend into the cave and understand the circumstances under which they were creating this art … it’s going to be an amazing experience,” he said.

Earline Green, a South Campus art instructor, said historical adventures, like the one Goode will partake in, is what visual art instructors look for and embrace. She said the Internet has made research more accessible but also muddier and will never replace the experience one receives when on those adventures.

“The Dozier Travel Grant will give Mr. Goode an opportunity to walk in the footsteps of noted scholars,” she said, “and allow him to make his own assessments. It will give him an opportunity to examine theories and artifacts firsthand.”

The Dallas Museum of Art awards the Dozier Travel Grant to local artists 30 years and older. To apply for the grant, Goode had to submit an application, proposal and budget and had peers submit recommendations in his favor.

“Various grants including the Dozier, which Mr. Goode received, is a jury panel which consists of museum staff, individuals from the local art community, among others,” said interim chief marketing and communications officer for the museum Jill Bernstein.

Goode received the grant and made the decision for the excavation based on his dream trip and what would benefit his students the most.

He has traveled all over the world for solo and group projects, including China, Italy, Malaysia and Spain.

The experiences and acquaintances he makes along the way he hopes to pass to his students.

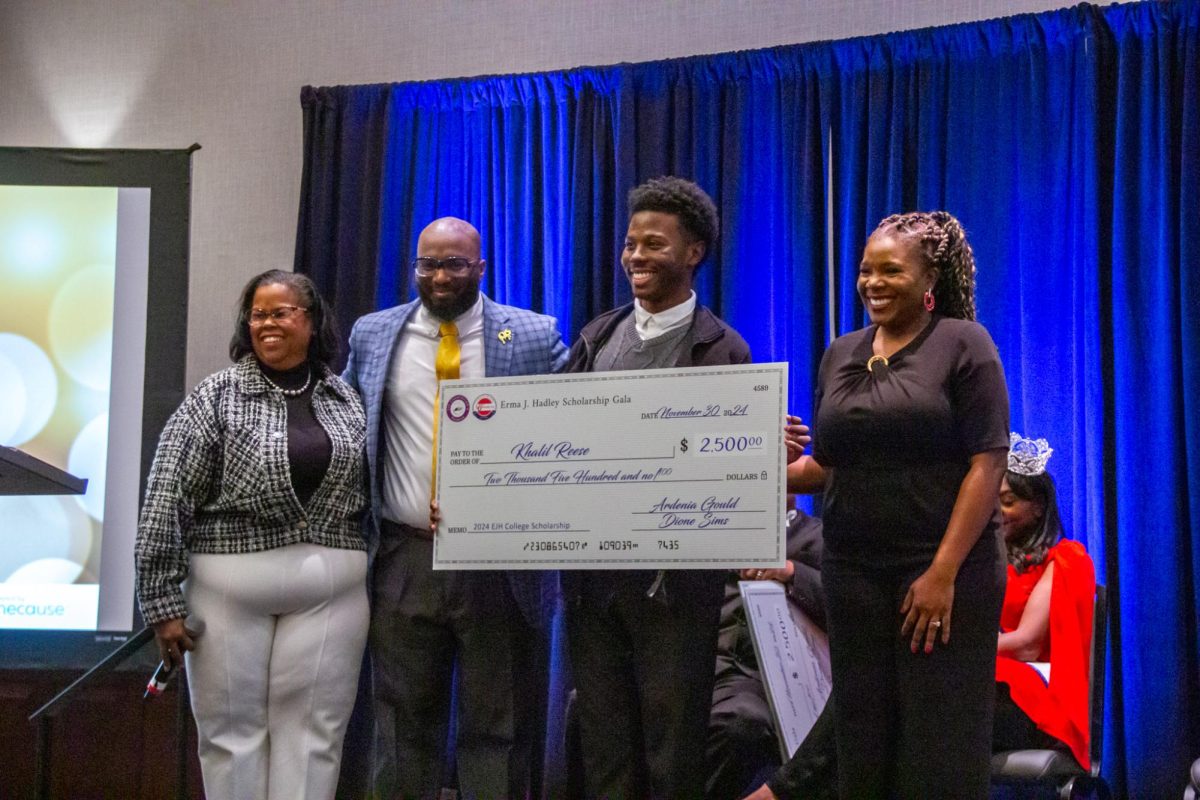

David Reid/The Collegian

“Something that has always been so helpful was my professional work. When I go out and I exhibit around the world or in New York making contacts there, I am able to help the students have a link there where I can provide opportunities for the students that they usually wouldn’t have,” he said.

Not only do his students now have opportunities outside of TCC, but they will have a glimpse into their possible futures.

“It helps them a great deal to see that you can be successful in the arts, that it can pay off and you don’t have to be a starving artist working in a studio,” Goode said.

Judith Gallagher, South divisional dean, said it is a great compliment to have the museum award Goode the travel grant.

“He is creating opportunities for other teachers and students on campus for South and the other campuses,” she said. “He’s really generous with his time he spends here in the art department.”

Though he does not have any planned exhibitions lined up after the dig, he wants to host a lecture that TCC faculty and students can attend to share what he has learned.

Goode said he cannot help but relate the Paleolithic man to the basic urge to create art and the spirituality that comes with that urge.

“What they’re finding more and more right now is that it’s really linked to almost Shamanistic rituals,” he said. “Getting into a trance state to create something, not necessarily in the idea that to create something beautiful for the sake of beautiful, but that it has an actual purpose in our development and how important art is to us as humans.”