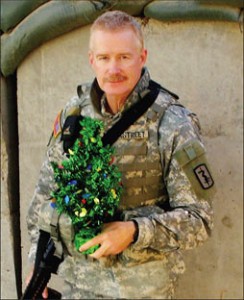

By Susan Tallant/editor-in-chief

This time last year, amidst bombs and gunfire, Dr. Charles Overstreet was south of Baghdad giving mental status exams to detainees and comforting soldiers traumatized by amputations, burns or loss of a brother.

Now, amidst hallways of giggling students with an iPod in one ear and a cell phone in the other, the South Campus psychology professor gives exams in air-conditioned classrooms. But his mind is still a world away.

“ It is hard to concentrate here because it is still going on over there,” he said.

Overstreet, a captain in the U.S. Army, has been on call since Sept. 11, 2001. He was deployed in March 2003 to Germany and deployed again in December 2005 for a 12-month tour in Iraq.

“ A part of me feels bad for not being there,” he said. “It is also hard to hear the casualty reports.”

WORK LIFE

Overstreet knows when the evening news report includes casualties, his former co-workers are very busy.

Work was performed under tents in a Forward Operating Base providing services to traumatized soldiers. He said many of the stressors with soldiers include problems with relationships at home and grief related to the loss of a buddy.

“ Our unit was scattered over Iraq,” he said. “We were broken up into med units, kind of like MASH, south and southwest of Baghdad.”

Overstreet said work life became very linear while in Iraq.

“ Same thing every day, work from 6:30 a.m. to 11 p.m. seven days per week,” he said.

Living conditions were not so great either. At times they would be up to their knees in mud, and the temperature would get up to 130 degrees.

“ You just move real slow, wearing full combat gear,” he said. “But the AC in the hummer would get it down to 95-100 degrees.”

Overstreet said he would have periods of boring, mundane down time, unlike the Americanized way of multi-tasking, running errands and focusing in several directions.

“ Then all of a sudden, something blows up,” he said.

At first the unit would all dive into the bunkers after hearing a blast. A few months later, they would just sit on the floor. Overstreet said after a while the sound becomes familiar. He even had to wake up a snoring friend at times.

“ If you can hear it, you didn’t get hit,” he said.

Now if Overstreet hears a car backfire or a slamming door, it makes him jump.

GETTING HOME

Getting Overstreet home was a mission all by itself. The task of getting to a green zone was perhaps the most difficult.

“ First, you have to get to Baghdad International Airport,” he said.

Overstreet said to get out of the danger zone he had to take a helicopter to Camp Liberty, travel by convoy and then by prop plane before riding a bus to the safer land of Kuwait.

He had mixed feelings about returning and said just the changing mind-set from one world to another is difficult.

“ I experienced a mix of anxiety and excitement about coming home,” he said. “Now that I am back to SUVs and watching Paris Hilton on TV, I think, ‘What are we doing? The Iraqis are suffering so much and we gripe about stupid stuff.’”

THE MEDIA

Overstreet knows the fluffy Hollywood stories will always dominate headlines, but he returned from Iraq with new respect for journalists out in the field.

“ Those guys, like from CNN, are out there in the theater getting shot at and blown up just to get the story,” he said.

Overstreet’s wife Jessica, assistant professor of history and geography on NW Campus, spent plenty of time watching news stories while her husband was deployed.

“ You’ve just got to watch it,” she said. “I feel better knowing what is going on.”

Jessica Overstreet said it is easy for Americans to take for granted life over here, like how clean and safe it is.

“ It’s not the fault of Americans in general,” she said. “It’s just our culture.”

THE PEOPLE

Unlike popular belief, Overstreet said most Iraqis are not hostile toward the U.S. as a population, they just live in fear and are afraid of everybody.

“ They just tell you what they think you need to hear so they will be safe,” he said.

“ Most are just trying to get by. They have to worry about someone breaking in their house and killing them.”

He said the ones who suffer the most are women, kids and the workers.

“ It’s a tough place,” he said.

As for support here in the U.S., Overstreet said it is ridiculous to hear people say Americans are not supportive of the military. He said even if people do not support the war, they always treat the soldiers with respect.

“ We would go eat at an airport and someone would go pay our entire tab,” he said. “We would constantly get care packages. People treat us great.”

Overstreet said it does not bother him that people exercise their freedom of speech and is glad they have the freedom to do so. He would rather see protesters than those who are just apathetic.

“ I’m always glad to see some willingness to participate … some passion,” he said. “The war protesters are saying they want the troops to come home. How could I be angry with that?”

STAYING HOME

Overstreet said with the way the war is going he has heard “rest up” a lot. He has just reached six months at home, so things could change soon.

“ They can re-deploy at six months. It’s still like being in limbo,” Jessica said. “I tell him to live for today, but it makes it hard.”

Overstreet misses his comrades. He said they were a really tight group of medical providers and chaplains and he feels lucky to have had the opportunity to be there.

“ [There was] lots of comedy and some rough-housing to burn off pressure,” he said. “And even when things were blowing up, you were never alone.”