By Edith Mariscal/ reporter

Photos by Bogdan Sierra Miranda/The Collegian

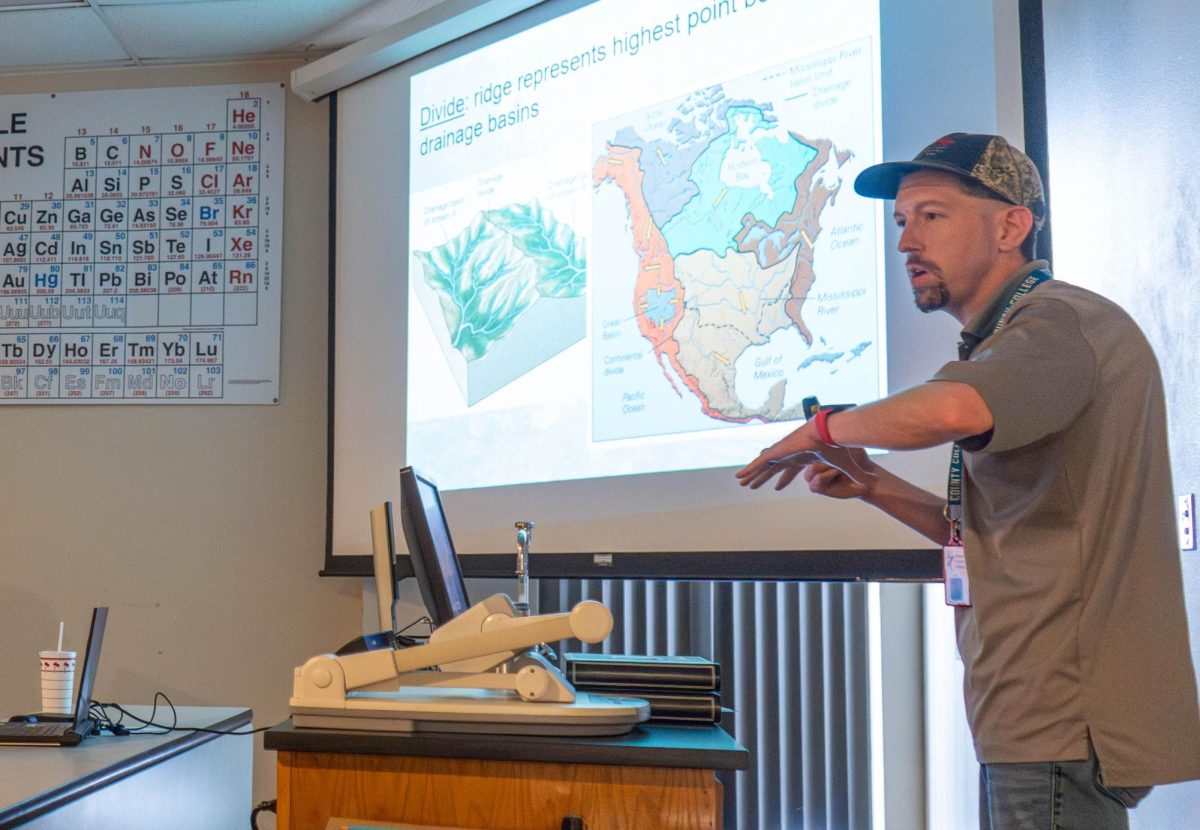

South students learned about the legal problems currently on Native American reservations during a Nov. 28 presentation by NE government professor Lisa Uhlir.

Uhlir discussed the dramatic rise in drug production, violence against women and poverty rates on reservations.

“Eighty percent of natives are high school dropouts, and less than 1 percent goes to college,” she said. “It’s a generational dysfunction.”

For Native Americans, the boarding school experience was their last hope and final attempt to remain on their land and hang on to their cultural traditions, Uhlir said.

“Boarding schools started around 1866,” she said. “They [officials] knew that they couldn’t change the inherent culture nature of an adult. If they were going to make the assimilation period work, they had to get to the children.”

Children were divided into groups, and different tribes were represented in each group in an attempt to remove them from their culture, Uhlir said. After being separated, their physical characteristics from clothing to haircut were changed to alter the way they looked.

“Native Americans feel their soul in their head,” she said. “Shaving their head meant you were starting new, normally after something dramatic in your life.”

Children were not allowed to speak their native language. They were punished for not speaking English, and diseases often happened because of lack of hygiene, Uhlir said.

“Forty to 50 percent of children that went to boarding schools died from a disease like tuberculosis, often because they didn’t have toilet paper, they shared towels and would sleep several children to a bed,” she said.

Group therapy provided a healing process for people who went to boarding schools, Uhlir said.

Students said learning about the schools was a shock.

“I had no idea,” South student Tifani Adams said. “I have children, so just imagining eats me up inside.”

South administrative office assistant Maisha Tsiboe said it gave her some insight into the issues natives face.

“Hopefully, it teaches us how to begin the healing process,” she said.