By Ayanna Watson/reporter

In 1973, one SE Campus English instructor could not get a library card without her husband’s approval and signature.

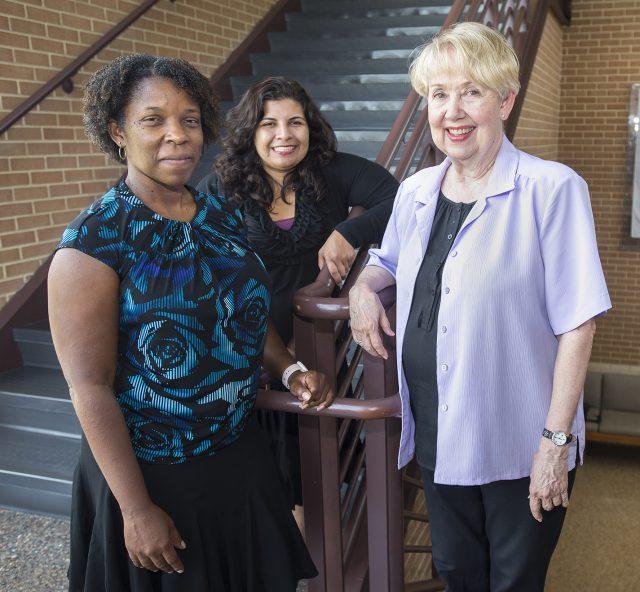

“I was a teacher in Houston, Texas, and I still couldn’t believe I had to have my husband’s signature just for a library card,” Violet O’Valle said.

O’Valle is one of three women instructors at TCC who shared how difficult a time they had proving they were as good as men.

When O’Valle was growing up, job qualifications were irrelevant when a man and a woman applied for the same job. People accepted the idea that a man deserved the job and ignored gender discrimination practices.

“Someone called me a ‘Tennessee gas girl,’ which meant I had a pretty face, and I was only good for my looks,” O’Valle said.

O’Valle didn’t feel as though things improved until the late 1980s. When she started working at TCC, she noticed the difference for women. She felt there were so many female administrators.

“The female chancellor [the late Erma Johnson Hadley] paved the way for many women and made me see how far women have come,” O’Valle said.

During her career, instructor Tamika Steward dealt with proving her worth as an employee in both education and management.

“I can accomplish anything, even if there is an obstacle,” Steward said. “Better yet, I can show you better than I can tell you.”

While working in management, gender discrimination pervaded Steward’s work environment. Men, in particular, did not want to talk to her if they had issues with employees and customers.

“I’m a military brat and never had to deal with race, ever, in my life,” she said. “It was such a new experience for me. I couldn’t believe I had to deal with this.”

When she began working in the school system, Steward said she thought students didn’t think they would learn anything from her because she was a woman.

“I had to prove I was smart enough to teach them,” she said.

Sociology instructor Monica Sosa faced challenges in her role as a mother, trying to build her confidence as a woman and overcoming Mexican-American stereotypes.

When she went to college in Chicago, she learned that people assumed she spoke Spanish because of her looks.

“It would be many times people would either make fun of me or just start speaking Spanish because I was a darker tone and looked the part,” she said.

A single mother and full-time instructor, Sosa had to learn time management.

“Having my daughter showed me real confidence,” she said. “I want my daughter to look at me and see the definition of a confident woman.”