When Shannon McDonald arrived to teach her summer Music Appreciation class, she walked into an empty room.

Her roster said there were 15 students registered for her blended class on NE Campus. It turned out none of them were real.

“I was flabbergasted and so confused. I just had no idea what was going on,” McDonald said. “I had no background that this was even a possibility, that they were all fraudulent students.”

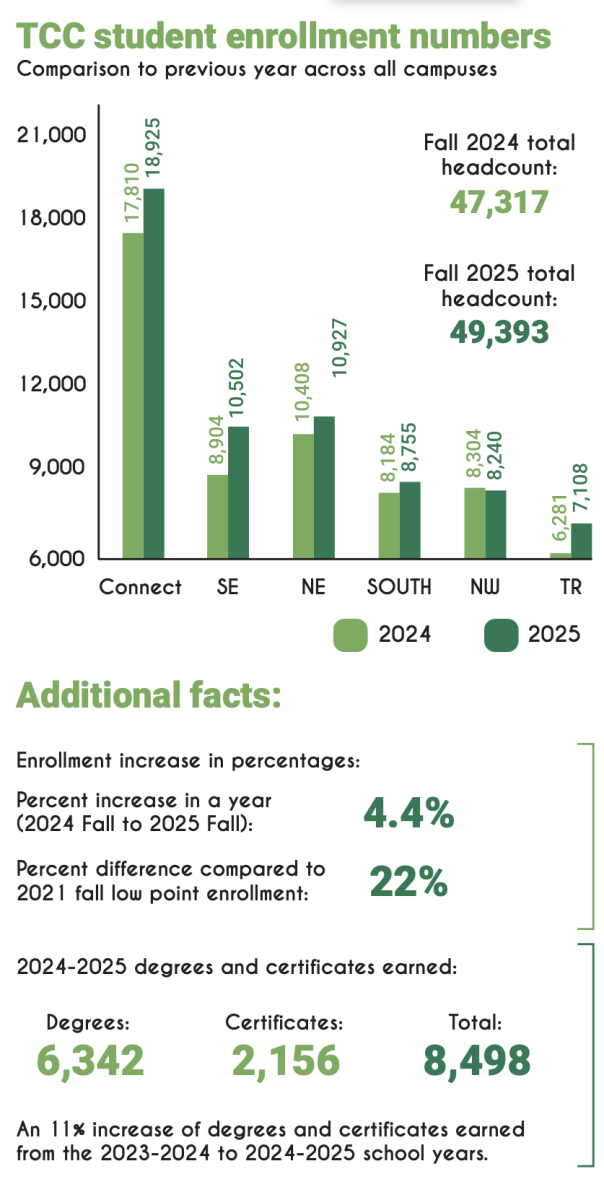

Fraudulent students are individuals who enroll for class with the intent to secure grants and loans through FAFSA by using stolen identities. This year, TCC has frozen 26,549 student accounts and labeled them as fake, more than triple the number in 2024.

“In 2024, we began noticing a rise in suspicious applications, prompting the college to establish internal processes to monitor and potentially identify fraud before these bad actors could reach the registration phase,” said TCC Provost Shelley Pearson.

It’s challenging to quantify the number of seats occupied by bad actors but according to Pearson, TCC is in the process of implementing a better way to detect suspicious applications at the point of submission before they can register for class.

If fraudulent students pass through this process and can register for classes, the next step for these bad actors is to wait until the census date.

“We’re giving our refunds to people that technically don’t exist,” said Sonya Brown, NE interim vice president of academic affairs.

Financial aid fraud is an issue she said her department is working with student affairs on how to identify in the classroom before financial aid disbursement.

“We need to see you face-to-face so that we can know that you are a real person,” Brown said. “But if it’s a blended course or an online class, how are we making sure I know that [student] is a real person.”

McDonald said she had assignments prepared in Canvas for the students to complete during the first two online days.

“Nobody did it, and I sent out lots of announcements to make sure they knew that’s what we were doing,” she said. “About four out of the 15 clicked on Canvas pages, but it was odd. It was like 40 pages in five minutes each, just showing they were active, but not actually doing the work.”

McDonald’s first in-person class was on a Wednesday. That’s when she realized something wasn’t right.

“Two hours and 50 minutes. I was sitting there the whole time, doing almost nothing, waiting for someone to show up,” McDonald said.

She reached out to music department chair Jerry Ringe and asked what to do. He advised her to email the students informing them if they did not show up for their in-person class the following Wednesday, they’d all be dropped from the course.

“I got one email from somebody that said they would be there, but they didn’t actually show up,” McDonald said. “Everybody was then dropped from the course, and I never heard from a single student about it.”

Before the students were dropped, she said she did her own investigation from the information she had available to her from the students.

“It was bananas. Pretty much all of them had a previous degree on their record and a lot of them had addresses that were out of state,” McDonald said.

She even Googled one of the student’s names.

“I got a LinkedIn profile of someone with the same email qualifications, and I’m quite sure that person was not the person enrolling in the class,” McDonald said.

As an adjunct instructor, she is paid by the school per class.

“I was really concerned that I was not going to get paid for an entire class. I gave up opportunities to do other things for the summer work to teach these classes,” McDonald said. “That’s my livelihood.”

Even though the class was canceled, McDonald was paid for the summer course.

District Director of Student Financial Aid Services Samantha Stalnaker said once fraud reaches her department it’s difficult to stop it, which is why new financial aid practices were implemented by the U.S. Department of Education this year.

These new practices are to help financial aid identify fraud and suspicious activity separate from legitimate students trying to get through the process.

“It is a balancing act,” Stalnaker said. “If we put too many roadblocks in front of students, then they get discouraged and aren’t able to come to school.”

Stalnaker said the admissions process is the first to identify fraud and freeze student accounts. By requiring student interactions through orientation, advising and placement tests, she said the affairs offices can connect enrollment applications to actual faces.

“Stolen identities will always be the most difficult [to identify], but once the college knows the patterns, we can target a specific group,” Stalnaker said.