By Kenney Kost/ne news editor

Photos by David Reid/The Collegian

A member of Discovery Channel’s Storm Chasers told NE and SE students that his job may be exciting, but his first priority is the truth.

Reed Timmer, a member of Team TVN on the show, said he focuses on accurate storm reporting.

“We want to provide the ground truth underneath the storm,” he said. “Most warnings you see scrolling across the bottom of your TV screen are from rotation and WSR88D radar, which is a network of stationary radars spread across the U.S. But the resolution of those radars isn’t fine enough to pick up all storms that produce tornadoes or pick them up in advance.”

Storm chasers can be out in the field and, with today’s technology, observe certain things that radar can’t pick up, Timmer said.

“We can see certain signs from the ground that may indicate a tornado might be occurring and relay that information to the National Weather Service and other local media to help out in the warning process,” he said. “So without storm chasers, I think the warning process would certainly suffer.”

Along with using technology in the field, Timmer said technology is also being implemented into storm reporting using live-streaming video.

“I think it’s [live-streaming video] the future of storm reporting,” he said. “Now, a forecaster doesn’t have to rely on phone calls or a radio transmission from someone. They can actually see what we are seeing through their own eyes and issue the warnings.”

The No. 2 priority is something Timmer said has become more important since the 2010-2011 seasons — disaster response.

In 2011, they were chasing a tornado that hit Yazoo City, Miss.

“We were there before emergency personnel, so we went house to house pulling people out,” he said. “I remember the looks in people’s eyes when they were coming up to us and needed immediate assistance, but they had injuries we weren’t trained to handle, and I just remember feeling so hopeless during that.”

Timmer said his entire team has now been trained in first aid and emergency response.

The 2011 tornado season was the worst season for tornadoes in U.S. history, he said. In April alone, close to 900 tornadoes were confirmed, beating the previous record of 267 from April 1974. The U.S. also had a record number of Category 5 tornadoes in 2011 with six, more than the combined total from the previous decade.

Timmer said most of the 2011 tornadoes happened in what he called Dixie Alley, stretching across Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky and Arkansas.

“Those [Dixie Alley] outbreaks are more damaging than the ones even here in Tornado Alley,” he said referring to the Southern Plains. “In Tornado Alley, most [tornadoes] happen in the afternoon, but in Dixie Alley, they can pop up anytime. On April 15, in Jackson, Miss., we saw a really strong tornado similar to one we would see in Kansas at like 6 p.m., at about 10 a.m. So, you have people taking kids to school and heading to work with all kinds of traffic on the roads. This can be a very dangerous scenario.”

Tornado research or the meteorology behind it is priority No. 3.

“The storms this season were perfect for science and intercepting because the tornadoes didn’t cause too much in the way of lost life or property at all,” he said.

Two reasons for this, Timmer said, were that most of the storms occurred in the Canadian Prairies with low population and sunlight as late as 11 p.m. and that most of the storms had low precipitation.

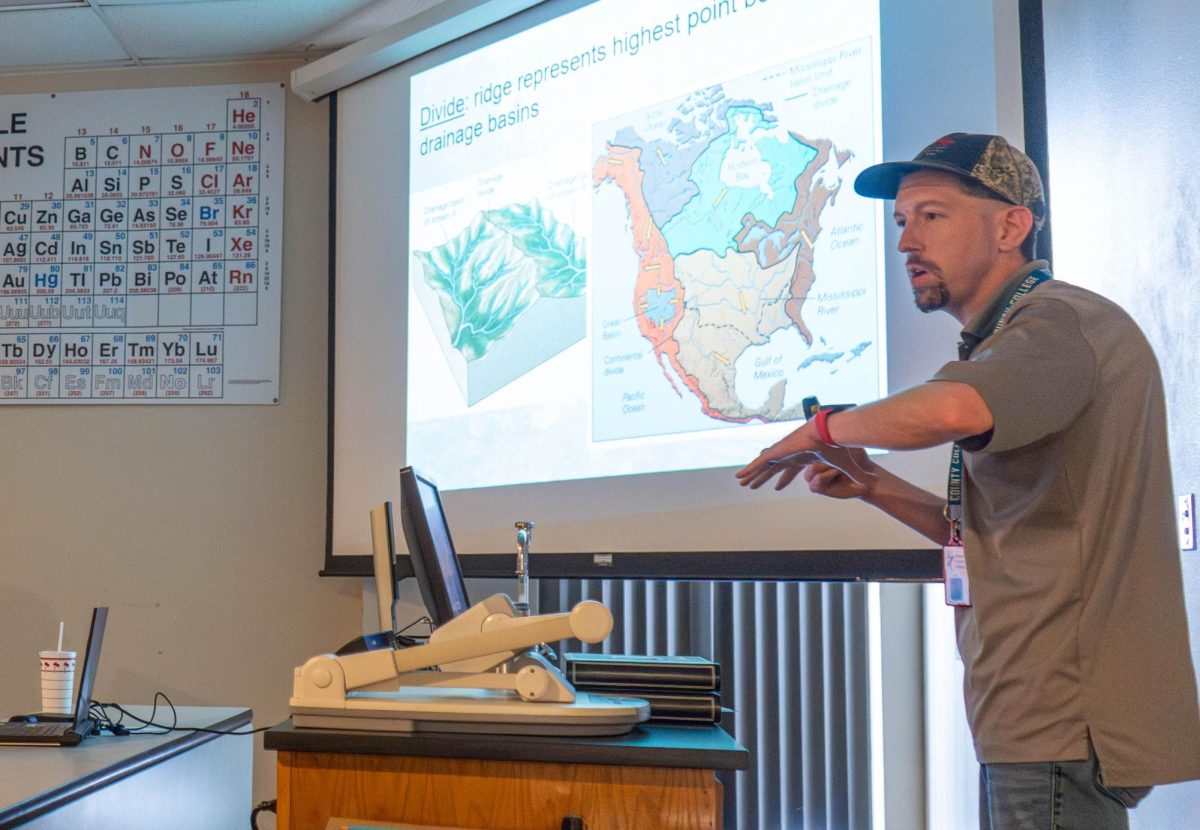

Timmer said with all the technology, computer models and math behind it, sometimes simple observation is underestimated.

“Sometimes a picture or video of the storm can give you a lot of info as well as field observation, and you really need that comprehensive merger between theory and what you see in real life,” he said.

As for the technology side and getting instruments close enough to or even inside the tornado, the team uses the Dominator 2 intercept vehicle.

The instrumentation on the vehicle consists of an X-band radar, which points straight up and measures updrafts and downdrafts; two anemometers, one measures pressure fall and the other measures horizontal winds; an air cannon system that launches projectiles cannons with parachutes into the tornado. These projectiles are then carried off by the storm and are later tracked measuring temperature, moisture and pressure at a rate of five times per second, he said.

“The goal with all the instrumentation is to get a 3-D X-ray of the tornado, not the whole vortex above the ground,” he said. “We are focusing right near the ground where things get really complex. That’s where the mysteries of tornado science lay in my opinion.”